How Colette Was Inspired By Her Many Cats

Susannah Fullerton on the French Writer’s Feline Muses

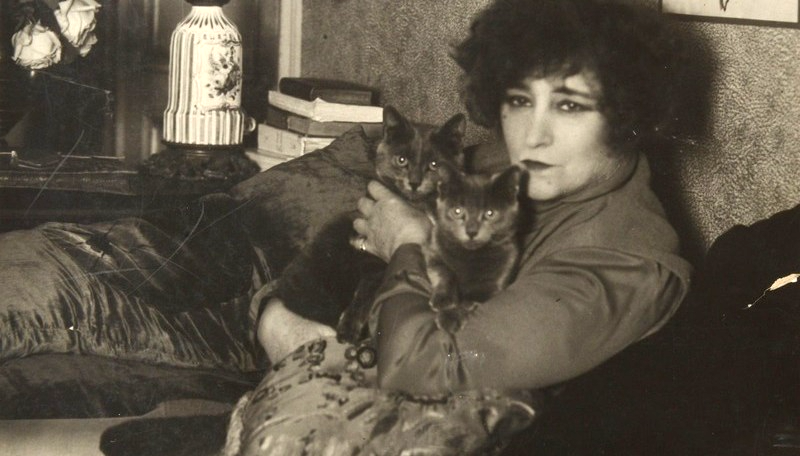

La Chatte condescended to live with Colette (Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette), born in Saint-Sauveur-en-Puisaye, France, in 1873, died in Paris, 1954, novelist, actress and journalist.

In 1926 Colette, the famous French novelist, attended an international cat show in Paris. Such events were a relatively new phenomenon in France—the first had been held just twenty years before—and Colette, as a passionate admirer of cats, was eager to see what a cat show had to offer.

The very first cat show ever held had been in London two years before Colette’s birth in 1873. This was a national cat competition at the Crystal Palace, and it attracted huge public interest (for the first time a Persian cat was seen by the British public). There is no detailed record, but it appears that somewhere between 150 and 211 cats were on display, and the public queued to admire them. Prizes were awarded for the biggest cat (he weighed 20 lb) and the fattest cat, and people saw for the first time many new, exotic breeds. Soon a second cat show was organized, this time permitting working men and women to enter their moggies for display. Two more shows were held in London, and Scotland also hosted a couple. The result of all this interest was the 1887 founding of the National Cat Club in England, a body which set standards for different breeds and chose judges to award prizes.

Colette rejoiced in the sensual nature of cats, the softness of fur, their rarely bestowed gestures of affection, their grace and agility.

These shows initiated a feline frenzy in Britain, which rapidly spread to Europe. Soon cat shows and competitions were being held in capital cities—Vienna had one, as did Berlin. Paris, as a city that saw itself as a leader of fashion, couldn’t possibly be left out. The first cat show in France was in 1896, and in 1913 the Cat Club de France was established. By 1924, however, there were ructions and the Cat Club de Paris became an independent body. That club established a stud book and register, the Livres des Origines. Famous people were frequently asked to be judges, to lend cachet to the events—novelists Émile Zola and Pierre Loti were two of them (both writers were cat-fanciers, so were well qualified to be judges). Most of the cat shows were held at the Jardin d’Acclimatation near the Bois de Boulogne.

In the late nineteenth century, public interest grew from simply admiring cats in shows to developing new breeds and collecting exotic cats. In 1869 only eight breeds were officially listed in La Vie des animaux illustrée. The latest trend among the bourgeoisie was owning distinguished cats, and Colette was no exception.What held her riveted at the show was a Chartreux cat (an officially listed breed), and before leaving she ordered a kitten from the breeder displaying there.

Chartreux are one of the oldest natural breeds in France. They are mentioned in a 1558 poem by Joachim du Bellay, “Vers français sur la mort d’un petit chat” (A small kitten’s death). They are thought to have originated in a Carthusian monastery in the Chartreuse mountains in south-eastern France. They are a large, muscular cat with relatively short limbs, orange or copper-colored eyes, and blueish fur (ranging from ash-grey to deep slate). Exceptional hunters, they were much prized by farmers. They are highly intelligent cats, which can be taught to do many tasks. Chartreux are known for their “smile”—on account of the tapered muzzle. They are calm observers of the world around them. They look rather like the Russian Blue, a breed more familiar outside of France. After World War I steps were taken to preserve the breed, to which end a “breed standard” was written. Generally, they weigh between 7 and 16 lb. It’s the tips of the fur which give the coat a blueish/silvery sheen. The Chartreux is usually a silent cat, giving little chirps or small miaows when wanting attention. They are adaptable, observant and polite animals. Charles de Gaulle admired them and named his Gris-Gris.

Colette soon welcomed her kitten and named her La Chatte. This seems a rather unoriginal name to be chosen by a woman whose talent lay with words. Soon author and cat were devoted companions. Time spent with cats was never wasted time in Colette’s opinion. She had loved cats since she was a girl; for her, no cat was ever ordinary. Her childhood home had always been a place for animals—in fact Colette’s forceful mother Sidonie had “boasted of her ability to housebreak pets and children.” Once Colette was in her teens, her feline companion was Kiki-la-Doucette (Kiki-the-demure), a grey Maltese, and she liked to take him for walks on a leash around the village of Saint-Sauveur-en-Puisaye in Burgundy.

In 1893 she married her first husband Henry Gauthier-Villars (always known as Willy) and they moved to Paris. But the move did not mean abandoning Kiki. Indeed it was her cat, her resolution to travel and see the French capital city, and her passion for solitude which were the invaluable things Colette took with her as “personal belongings.” Kiki travelled with her to Paris, though struggled to adjust to an apartment lifestyle after the freedom of the countryside. The distressed animal “roamed around depositing his wastes everywhere except in the designated receptacle.” Her nickname for her new husband was also Kiki-la-Doucette, which must surely have caused confusion in the Willy household, but Willy took it as a sign of love, and felt honored that she’d bestowed her cat’s name upon him.

In 1900 Colette’s novel Claudine at School was published under Willy’s name, and was an instant success. It was followed by three more popular books about the naughty schoolgirl. Claudine is given her creator’s love of cats. Her cat is Fanchette, a cat of great character, though she looks ordinary. Fanchette and Claudine share a special bond and Claudine knows her pet wants sex as much as she does, “so I asked round among the neighbours. The maid downstairs lent me a lovely husband for her, a fine striped grey.” Soon Fanchette is expecting kittens.

When Kiki died in 1903, Colette was devastated. She turned to her pen as a way of dealing with her grief and wrote Dialogues de Bêtes, a quirky one-act play between Kiki-la-Doucette and Toby-Chien, Colette’s French bulldog. This was published in 1904. Toby-Chien is loyal, rambunctious and devoted, while Kiki is standoffish and narcissistic, and the conversations between them are cleverly comic.

Colette separated from Willy in 1906 and they divorced in 1910. Husbands could come and go, but cats were a constant joy. Always sensuous and daringly modern in her choices of lovers, Colette rejoiced in the sensual nature of cats, the softness of fur, their rarely bestowed gestures of affection, their grace and agility. Cats were her muses and appear in many of her works. There’s an old piece of Pathé film (which can be seen on YouTube) showing Colette, at the time of her second marriage, happily playing with her cats and a dog. Animals were vitally important in her life. She believed them incapable of deceit and far above humans when it came to integrity. She tried to emulate them and even once appeared on a dance-hall stage dressed as a wildcat.

In 1912 Colette married Henry de Jouvenel, editor of France’s first daily newspaper Le Matin. He was somewhat astonished by his wife’s passion for cats. “One of these days you’ll retire to a jungle,” he warned her, adding “when I enter a room where you’re alone with your animals, I feel I’m being indiscreet.” That marriage too ended in divorce—she had an affair with his sixteen-year-old son Bertrand, while Henry indulged in affairs with women who were less cat-obsessed and didn’t make him feel an awkward third.

In 1925 she met Maurice Goudeket, who became her final husband. He shared Colette’s love of felines and admired her almost religious fervor for animals. The letters she wrote to Maurice are full of the doings of her cats. It was Maurice who was in her life when the new Chartreuse, La Chatte, arrived as a kitten.

Colette was by this time an established and famous writer. Chéri, La vagabonde and Le Blé en herbe had all been published to great acclaim. In 1926, the year of La Chatte’s arrival, she moved to an apartment in Paris’s Palais-Royal, although she also had a country home in Provence. Her lifestyle was a nomadic one and she moved often. More Chartreux cats joined the family—Minionne, Pinichette, Petiteu, La Touteu and Zwerg were some of them. Colette was often photographed at her desk, with cats in her arms. A photograph taken around 1938 shows her outdoors forming a relationship with a street tabby. Cats gave her aesthetic pleasure and comfort—her ideal of beauty was a sleeping cat. She delighted in her cat’s beauty, the softness of its fur, its large unblinking eyes, the unrivaled loveliness of its paws and its twitching ears. Even delicate feline nostrils and curved claws that could scratch like thorns won her undying admiration.

In 1925 she assisted her friend, composer Maurice Ravel, by writing the libretto for his one-act opera L’Enfant et les sortilèges (The Child and the Spells). It includes a love-duet “Duo miaulé” between Le Chat (baritone) and La Chatte (mezzo-soprano). Colette must have loved penning the dialogues, for the whole opera took her only eight days to write.

The London Review of Books has described Colette as “the frizzle-headed Cat Woman of 20th-century French writing”—there are worse ways to be remembered.

Her 1928 novel La Naissance du Jour (Break of Day) is strongly autobiographical. In it she celebrates the simple pleasures of life—one of them being an evening stroll along the coastal path with her coterie of cats. Her Provençal garden becomes a paradise because cats consent to spend time with her there.

In 1933 Colette immortalized La Chatte as Saha, the dainty Chartreux heroine of the novella La Chatte. She is much adored by a young man named Alain, who is as secretive and reserved as his cat. He bought Saha at a cat show because of her “perfect face, her precocious dignity, and her modesty that hoped for nothing behind the bars of a cage.” He loves her golden eyes, and the pearl-grey of her ladylike ruff. The two of them sleep together in his childhood bed. When Alain marries Camille, she is jealous when she learns that she comes a distinct second to the cat. Camille is more like a large and energetic Labrador in personality—lusty in bed, demanding of her husband’s attention. “How could she be your rival?” Alain asks his wife. “You can’t compete with the pure; your rivals have to be among the impure.” Goaded beyond endurance by Alain’s words, Camille tries to kill her feline rival. She shoves Saha off the ninth-floor balcony. A fifth-floor awning breaks the fall and Saha survives. Camille must face Alain’s fury—and she is the one who has to leave. She gets to keep the car, while he keeps the cat. When she looks back at him one last time, she sees him caressing Saha in the garden. Saha and Alain live together to their mutual satisfaction, with Saha “purring full-throatedly” to the end of her days.

To Alain, his cat embodies childhood, which he is unable to leave behind him. Only Saha’s death will end her hold on him. The novella’s extraordinary version of the eternal triangle is rather disturbing. It was written in prose that Colette’s biographer Judith Thurman describes as “particularly feline—both detached and voluptuous.” The cat is mistress and heroine of the story; while Colette shows little respect for Alain or Camille, Saha is obviously worthy of authorial admiration. As Colette wrote this work, she had only to look within the room for descriptions of Saha’s appearance and behavior. Saha is “a little, innocent animal as blue as the best dreams,” faithful, fastidious—a replica of her own beloved La Chatte.

Weary of constant moves, Colette settled again at the Palais-Royal in 1938. It was in her first-floor apartment, with garden views, that La Chatte and Colette both spent their last days. By early 1939 La Chatte was ill with cancer and Colette sorrowfully had her put down in February. She vowed never to have another cat, even though she found it upsetting to be living without an animal for the first time in her life. Perfect friends are invariably four-footed was Colette’s sad conclusion.

Colette, like a cat, had lived nine lives by the time she died in 1954. She was a Nobel Prize nominated writer, a music-hall performer, an intellectual, a beautician (it was said women exited her salon looking ten years older than when they went in), a journalist, a lover of both men and women, a mother (although a very poor parent to her only child, Colette de Jouvenel, always known as Bel-Gazou), wife to three different men, and a lover of cats. People said that her eyes resembled a cat’s, and she certainly had the independence and spirit of the “cat that walked by itself.” The London Review of Books has described Colette as “the frizzle-headed Cat Woman of 20th-century French writing”—there are worse ways to be remembered.

__________________________________

Reprinted with permission from Great Writers & the Cats who Owned Them by Susannah Fullerton. Published by Bodleian Library Publishing. Text copyright © 2025 by Susannah Fullerton. All rights reserved.

Susannah Fullerton

Susannah Fullerton is an author, literary lecturer, and leader of popular literary tours around the world.