How Close Did We Come to Losing Beowulf Forever?

Robert Bartlett on a Vital Work of the Western Canon That Barely Survived Multiple Disasters

There are cases of important literary and historical works that survive in only one or two manuscripts. If they had suffered some accident, then our picture of the past might be altered in important ways. An interesting and unusual case is provided by the long poem that the Roman author Lucretius composed around 50 BC. In many ways it would not seem a likely candidate to be copied out by medieval monks, for it presented a completely materialist picture of the world.

All that exists, says Lucretius, are atoms and the void; the atoms are infinite in number, have size and shape but no intrinsic qualities of color, smell, etc., and their various combinations make up all that exists. The universe is infinite and contains many worlds. To say that the gods created our world is “an act of folly.” The world will end. Mind or spirit is mortal and physical and thus cannot exist without the body. Death is the end. Religious rites and ceremonies have no effect. Hence, there is no immortal or immaterial soul, no afterlife, all is explained by the movements of matter. Yet, despite this thorough materialism, the survival of Lucretius’ poem depends entirely on two manuscripts copied out in the Carolingian period, and one of them was certainly at the royal court, where it was studied and annotated by the Irish scholar Dungal. We cannot know who commissioned them or what the scribes thought about the work, but it is a remarkable fact that the survival of the longest and most eloquent expression of ancient materialist philosophy depends on the narrow thread of those two copies made in the ninth century by Christian scribes.

Because the manuscript transmission was so thin, Lucretius had no direct influence on medieval thinkers. Only in 1417, when the bibliophile Poggio came across a manuscript of Lucretius’ work (it no longer exists but was probably a copy of one of the two surviving Carolingian manuscripts) and made it available for copying, and, even more definitively, in 1473 when the first printed edition of the poem appeared, was this part of European cultural history truly recovered.

This major record of early Germanic heroic verse is now a secure part of European cultural history. But it was a close thing.

Another remarkable example is the historical work of Zosimus, which was probably composed in the years 498-518. By this time, the eastern Roman empire, where Zosimus lived, had been fairly thoroughly Christianized, but Zosimus was a pagan hostile to Christianity. His New History is one of the texts listed and commented upon by Photius, who calls him “impious in matters of religion.” Zosimus blamed the decline of the Roman empire on the neglect of the old gods and suggested that the emperor Constantine had accepted the new religion because it offered him a chance to wash away the guilt for the hideous crimes he had committed. Surprisingly, Zosimus’ history belongs to the 36 per cent of works listed by Photius that survive to this day—but only just. There is one manuscript, and this has several sections removed, perhaps ones that were extreme in their hostility to Christianity. The manuscript seems to have been written in Constantinople and was in the Vatican library, where it still is, by 1475. It leaves the question of how representative our surviving sources are and whether Zosimus’ views were more widespread than existing evidence suggests.

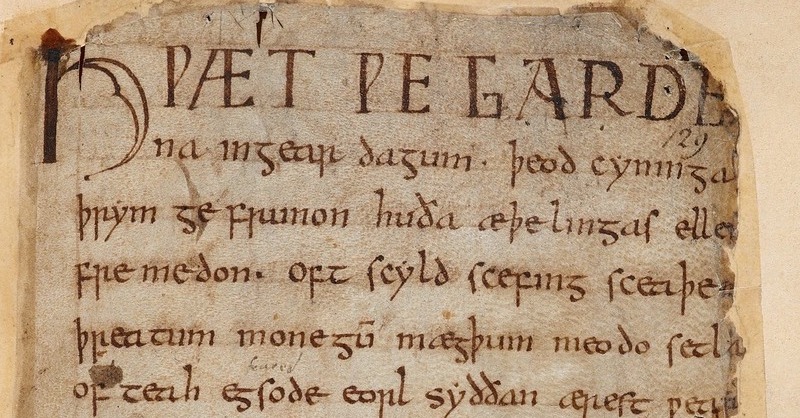

The dangers of manuscript transmission and the wild chances and accidents that dictate what we know of the past are well illustrated by the epic poem Beowulf. Beowulf is the longest poem in Old English, representing more than one-tenth of the total surviving poetry from the Anglo-Saxon period, and it is also the best known. It tells the dramatic tale of the hero Beowulf, who fights and kills the monster Grendel, then confronts Grendel’s mother in her underwater lair after she had come seeking revenge, and cuts her down. Fifty years later, after ruling his people well, he has to face a marauding dragon, which he kills after a fierce fight, but then dies of his wounds. The poem ends with the hero’s burial and the laments of his followers. It presents a heroic, elegiac and very alien view of the world.

Beowulf has been translated dozens of times, into many languages, and has inspired films, video games and graphic novels. But this whole edifice hangs by a thread, and a study of how the poem has come down to us reveals many moments when the work could easily have disappeared for ever. It survives in one manuscript, written in England in the decades around 1000, judging by its script, but then nothing is known about it for more than 500 years. In 1563, it was in the possession of the Tudor scholar Laurence Nowell, who helpfully wrote his name and that date at the top of the first page of the poem, but there is no indication of how he had acquired it or where it had been in the Middle Ages, although one assumes it had slumbered in a monastic library until the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII. Nowell was a pioneer in the study of Old English texts (he created an Old English vocabulary 187 folios in length), so it fits in well with his main scholarly interest.

Not long afterwards, the Beowulf manuscript somehow came into the library of Sir Robert Cotton (1571-1631), a famous book collector, whose manuscripts eventually were to form part of the core of the British Museum (and of the British Library when this was separated from the Museum in 1973). Cotton was from the landed class, received a legal education and served several times as a Member of Parliament; he was deeply involved in politics, sometimes riskily so, in this period when the battle lines were beginning to be drawn that led eventually to civil war between king and Parliament. He was also renowned as an “antiquary,” indeed being an early member of the Society of Antiquaries, a group of gentlemen who met weekly to discuss legal and historical matters.

Over the course of time, Cotton’s personal collection of manuscripts came to number 800 volumes. He was generous in giving access to his library—as a contemporary wrote, he won fame “not only from his collection of books and manuscripts of the choicest sort acquired at vast expense but also through his kindness and willingness to make them available to students of good literature and affairs of state.”

In the time of his grandson, John Cotton, a printed catalogue of the manuscripts in the collection was published. The Cottonian library had an unusual cataloguing system. Because the bookshelves were adorned with busts of the early Roman emperors, individual volumes were identified by the emperor whose bust stood above them (Julius Caesar was treated as the first emperor and two female figures, Cleopatra and the empress Faustina, were also included). As a consequence, manuscripts from the Cotton collection have shelf marks such as Julius D X or Tiberius D III, and lists of such manuscripts are not arranged alphabetically but follow the sequence of Roman emperors. The manuscript containing Beowulf has the shelf mark Vitellius A XV.

However, in the catalogue of Cotton’s manuscripts published in 1696, Beowulf is not even noticed among the contents of Vitellius A XV, a warning that catalogues are not always comprehensive (the catalogue entry appears to be based on Cotton’s own contents list in the manuscript, which likewise omits Beowulf). The first mention of the poem is a few years later, in Humfrey Wanley’s catalogue of Old English manuscripts in English libraries, published in 1705. Its existence was now public knowledge. Even more importantly, between the time of the 1696 catalogue and the publication of Wanley’s work in 1705, the whole magnificent collection of Cotton manuscripts had been gifted by John Cotton “for Publick Use and Advantage,” secured by an Act of Parliament and the creation of a body of trustees, a very early example of a cultural treasure donated “to the nation.”

At the time of the donation, the manuscripts were kept in Cotton House, a family property adjacent to the palace of Westminster. This building itself was purchased by the Crown in 1707, but was in a state of dilapidation, and in 1722 the library was moved to Essex House in the Strand, and then again in 1729 to Ashburnham House, Westminster, which was judged “much more safe from fire.” Few opinions have been as wrong as that one. On the night of October 23, 1731, Ashburnham House went up in flames. The Parliamentary committee that was established to investigate this disaster reported that of 958 manuscripts housed there, 114 were “completely destroyed,” and 98 “considerably damaged.” Some treasures of the Anglo-Saxon period were lost: a version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (that known as “G” and often associated with Winchester); the sole medieval copy of Asser’s Life of King Alfred; and the sole medieval copy of the Old English poem known as The Battle of Maldon, describing the last stand of ealdorman Byrhtnoth against the Vikings.

Fortunately, copies of these works had been made by antiquarians and scholars in the Tudor period and later, and printed editions published before the fire. The G version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle had been copied by Laurence Nowell, the same man who had owned the Beowulf manuscript, and an edition of the text from the Cotton manuscript had been published in 1644. Asser’s Life of Alfred is preserved in several sixteenth-century transcripts and editions (usually with additions) and had been published by Matthew Parker, the archbishop of Canterbury, in 1574 (he added the story of Alfred and the cakes), and by Francis Wise in 1722. Wise’s edition contained a facsimile of the opening page of the Life, which has allowed informed comment on the layout and handwriting of the lost manuscript.

A transcript of The Battle of Maldon was made less than a decade before the fire of 1731 and printed in 1726. So, although the books were lost, the texts were not. Beowulf was both more fortunate and less fortunate than these other Anglo-Saxon works—more fortunate in that the manuscript, although damaged, was not destroyed by the fire, less fortunate in that no transcripts had been made before 1731. If the Beowulf manuscript had been destroyed in the fire, all we would know of it would be the forty lines Wanley cited in his catalogue of 1705 and his brief and misleading summary: “in this book, which is a remarkable example of Anglo-Saxon poetry, are described the wars that Beowulf, a certain Dane, from the royal stock of the Scyldingas, waged against the petty kings of Sweden.” No Grendel, no Grendel’s mother, no dragon.

Beowulf survived. But what other works have been lost so completely that we do not even know they have been lost?

The damage to the Beowulf manuscript, Vitellius A XV, involved destruction of the spine and binding, so that only detached leaves survive. Hence there is no evidence of the construction of the codex, and it took some time to re-establish the proper order of the leaves. More seriously, the edges were damaged and brittle, and loss of letters at the beginning and end of lines continued long after the date of the fire itself. Some of the lost writing can be restored from a perhaps unexpected source. The story of Beowulf is set, not in England, but in Scandinavia, and hence drew the attention of scholars from that part of Europe. In 1787, the Icelandic scholar Grímur Jónsson Thorkelín visited London and was responsible for two transcriptions of the manuscript, one commissioned from a copyist, the other which he copied out himself.

Armed with these he returned to Copenhagen, where he was based, and began work on producing a printed edition of the poem. He labored on this for twenty years and by 1807 had a text that was ready for printing. In the meantime, the French Revolution had occurred, Napoleon had risen to power and conquered half of western Europe, and various combinations of France’s enemies had formed coalitions to stop him. Britain was France’s most persistent opponent and was determined to control the seas, especially in the face of Napoleon’s efforts to blockade the country. Although Denmark was neutral, both sides sought to enlist it, and the British government expressed fears that the Danish fleet would be used against Britain, either as a result of an alliance of Denmark with France or through French seizure of the fleet.

In response, Britain sent a strong naval expedition into Danish waters which, from September 2-5 1807, bombarded Copenhagen. Especially damaging were the hundreds of rockets, which set fire to the city, reportedly destroying a thousand houses in the Danish capital. Part of the collateral damage was the manuscript of Thorkelín’s edition of Beowulf (though not his two transcripts). The British navy had destroyed the first attempt to print the most important early English poem.

Or at least that is what Thorkelín said in the preface to his edition, when it was finally published in 1815 (along with a Latin translation). Some have doubted him, and wondered whether the British rockets were just the ideal excuse for taking twenty years not to publish an edition. And the edition, when it did come out, was subject to withering criticism. John M. Kemble, who published the next edition in 1833, did not pull his punches in discussing his predecessor: “not five lines of Thorkelin’s edition can be found in succession, in which some gross fault either in the transcript or the translation, does not betray the editor’s utter ignorance of the Anglo-Saxon language.” However, whatever his scholarly failings, Thorkelín had at least been responsible for two transcripts of the poem, and, as the manuscript itself had continued to deteriorate, chiefly by flaking of the brittle margins, these were a valuable record of the original. The transcripts survive, in the Royal Library in Copenhagen, and have even been reproduced in facsimile.

Kemble’s edition has been followed by many others, all of which have to rely on a combination of what can be read in Vitellius A XV, what Thorkelín’s transcriptions can supply and what an educated editor might guess. There remain many disagreements in detail but hardly any in essence. This major record of early Germanic heroic verse is now a secure part of European cultural history. But it was a close thing.

Surviving unread and uncopied for 500 years in some English monastic library, the manuscript passed through the turbulence of the dissolution of the monasteries and the scattering of their books, not to end up on a bonfire or to be used as a convenient wrapping for butter or fish, but to come into the hands of Tudor antiquarians and book lovers, only then to pass through the ordeal by fire of 1731, surviving but only just. It was not until 1787 that a copy was made, not until 1815 that it appeared in print, not until 1833 that there was a reputable edition. So, Beowulf survived. But what other works have been lost so completely that we do not even know they have been lost?

__________________________________

Excerpted from History in Flames: The Destruction and Survival of Medieval Manuscripts by Robert Bartlett. Copyright © 2024, 2025 by Robert Bartlett. Excerpted with permission of Cambridge University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Robert Bartlett

Robert Bartlett is Bishop Wardlaw Professor of Mediaeval History at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. He received his university education at Cambridge, Oxford and Princeton, taught earlier at the universities of Edinburgh and Chicago and has held fellowships at the universities of Michigan, Princeton, Göttingen and Tel Aviv, and at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. He has published on the history of England, 1066-1300; the cult of the saints; and on frontiers and colonization in medieval Europe.