How Christopher Columbus’s Brutal Enslavement of Indigenous Caribbeans Set the Tone For the “New” World

Imaobong Umoren on the Violent History of the Colonized Caribbean

The decades of exploration in the Caribbean and Spanish encounters with indigenous peoples, and the use of enslaved labor in mining, would lead to the cultivation of critical crops—namely, sugar—that would soon come to be developed using enslaved African labor. Spanish control of the Caribbean paved the way for English, and later British, domination in the region, following the 1707 Acts of Union with Scotland.

This early modern period would set the foundations of the rise of the transatlantic slave trade and a new form of slavery—hereditary racial slavery—that would be central to the creation of the racial-caste hierarchy and to the rise of Britain’s wealthy and brutal Caribbean slave empire. It would come to usher in a key moment within the history of modernity. And it would come to completely upend, forever, the Caribbean.

Around seven thousand years ago, indigenous peoples embarked on a northern migratory path from South America to Trinidad, then still a part of mainland South America. Over the course of thousands of years, more continued this journey, moving beyond the Eastern Caribbean and reaching what is today Puerto Rico. In around 4000 BCE others from Central America moved from the Yucatán peninsula to Cuba, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico. Most of these migrants were fisher-hunter-gatherers and belonged to numerous ethnic groups who left vital evidence of their presence in stones, burial sites, and artifacts.

Taíno societies were matrilineal in their descent, meaning that women could be chiefs and that power was transferred from the chief’s mother’s relatives.

Another wave of migration occurred around 2500 BCE. Coming from the Orinoco Basin in South America, groups of agriculturalists settled in villages in the western and eastern parts of the Caribbean, speaking languages derived from the language family known as Arawakan. Over time, more developed societies began to appear in Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. Some of these peoples are collectively known as Taíno, which does not necessarily describe a specific group but rather is an adjective, loosely defined as noble or good. The Taíno enacted a broad set of sophisticated cultural practices shared by several cultures that occupied the Caribbean.

It is difficult to know all aspects of Taíno daily life due to a lack of sources, but Spanish chroniclers (such as Las Casas) recorded a considerable amount of information about them. Using new archeological and ethnohistorical research, recent scholars have built on these works. They suggest that over hundreds of years Taíno society developed from being organized along tribal lines to chiefdoms. Chiefs or caciques held godlike powers and could order laborers to cultivate land or serve in military encounters. Their society was hierarchical, with those below the caciques known as the nitaínos (elites), behiques (perhaps shamans), and the naborías (usually servants and commoners).

Taíno societies were matrilineal in their descent, meaning that women could be chiefs and that power was transferred from the chief’s mother’s relatives. Labor was gendered: men took to hunting, while women focused on agricultural work, cooking, cloth-making, child-rearing and harvesting. Taínos cultivated different crops ranging from fruits to sweet potatoes, yams, and peanuts.

The Taíno were not the only indigenous peoples residing in the Caribbean at this time. Another group, known as the Caribs, moved from South America and lived in the Lesser Antilles, the eastern part of the Caribbean. “Caribs” is a Taíno term meaning islanders, but the Caribs referred to themselves as Kalinagos, or sometimes Kalipuna. The surrounding sea, the Caribbean, is named after this group.

While many details about indigenous peoples’ lives remain mostly unknown, what is certain is that by the fifteenth century they inhabited most of the islands in the Caribbean.

While Europeans regarded the Taíno as peaceful, they called the Kalinago “careless and lazy creatures,” and “so vindictive there are no people more ready to take vengeance on anyone who has offended them.” Unlike Taínos, Kalinago activity tended to focus on trade and war. When they encountered Europeans, they would often put up a daring defense. In response, Europeans spread the myth of their cannibalism, which would be used to justify their enslavement. But there is no evidence that Kalinago peoples were cannibals.

Alongside Taínos and Kalinagos, the Caribbean was home to other groups: the Guanahatabeys, who occupied parts of Cuba, and the Lucayans, who lived in the Bahamas. While many details about indigenous peoples’ lives remain mostly unknown, what is certain is that by the fifteenth century they inhabited most of the islands in the Caribbean, with suggestions that their population was, adopting a conservative assessment, around 2 million by 1492. In this year, indigenous peoples first met European explorers, ushering in a new phase of globalization that would connect the Caribbean to the rest of the world.

On August 3, 1492, the Genoese captain Christopher Columbus set sail on the Santa María from Palos, in the Bay of Cádiz on the coast of Spain, with around forty crewmen, alongside two smaller caravels, the Niña and the Pinta. They ventured first toward the Canary Islands before setting off across the Atlantic. Six thousand kilometers later, they arrived on the Caribbean island known by the Taíno as Guanahaní, which today is part of the Bahamas. Columbus took control of the land in the name of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain and gave it a new name—San Salvador, meaning Holy Savior.

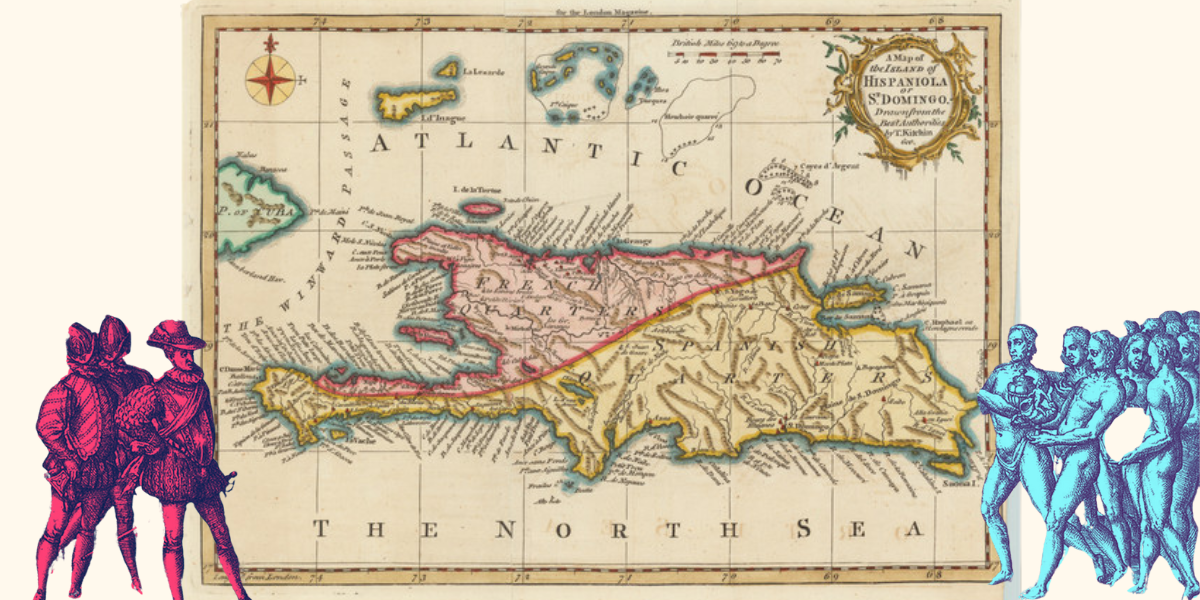

Next, he and his crew moved along the north coast toward what was known as Quisqueya/Haiti, which he renamed Española or Hispaniola. Here, his ship ran aground. He sent some of his crew to find the Taíno cacique Guacanagarí, who sent for canoes to aid the Spaniards.

Later Columbus made an agreement with Guacanagarí whereby he agreed to fight the chief’s enemies—in this case the Kalinago—for information on the location of gold mines. Columbus continued to search for gold before sailing to the neighboring island, now known as Cuba. He eventually arrived back in Palos in March 1493, bringing with him some indigenous peoples.

Columbus’s historic journey to the Caribbean occurred amid significant changes in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, including the exploration of the Canary Islands and Cape Verde, the weakening of Islam, and the rise of Christianity in the form of Catholicism. Born in 1451 or 1452, Columbus grew up in Genoa, a commercial and financial center. His career began on Portuguese ships, where he learned how to navigate the Atlantic on voyages to the African coast. Columbus was involved in transporting sugar, a profitable and popular new crop, from Madeira to Genoa.

Often romanticized and glorified as a triumphant moment in Western histories, Columbus’s travels wreaked havoc in the Caribbean, which became one of the key areas for European expansion and subsequently violent accumulation.

Around 1478 or 1479, he married a Portuguese woman from an aristocratic family and went on to climb the ranks as a mercantile agent before sealing his reputation as an intrepid geographer. Passionate about the discovery of new lands, he set his sights on the gold and riches rumored to exist in Asia. Indeed, when Columbus arrived in the Bahamas, he thought he had reached Asia.

Columbus’s voyage occurred during a pivotal moment of change within European politics and political economy. In this age of discovery, new maritime technologies including the caravel, information tools like the printing press, and changes in the process of loaning money all helped contribute to an upswell of European traders looking for new markets to conquer by force. Often romanticized and glorified as a triumphant moment in Western histories, Columbus’s travels wreaked havoc in the Caribbean, which became one of the key areas for European expansion and subsequently violent accumulation.

A sense of surprise, wonder, and intrigue likely shaped the moment the Taíno and Spanish first set eyes on each other. The Spanish were small in number, and so they possibly did not spark immediate fear. In his diary, Columbus noted that the Taíno:

all go naked as their mothers bore them, including the women . . . They were very well built with fine bodies and handsome faces. Their hair is coarse, almost like that of a horse’s tail and short; they wear it down over their eyebrows except for a few strands at the back, which they wear long and never cut. They are the colour of the Canary Islanders (neither black nor white)…They do not carry arms or know them. For when I showed them swords, they took them by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance.

Columbus identified the Taíno as inferior to Europeans, noting: “They should be good servants and very intelligent, for I have observed that they soon repeat anything that is said to them, and I believe that they would easily be made Christians, for they appeared to me to have no religion.” His initial categorization of Taínos was to have profound consequences for the success of Spanish colonization.

Encouraged by his first voyage, where he found small amounts of gold, Columbus embarked on a second in 1493. This time he went with the clear goal of establishing a trade colony with a royal monopoly in Hispaniola for his patrons Ferdinand and Isabella. The marriage in 1469 of the cousins Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castille united the Spanish Crown and would see Spain become a major European power. Known as the Catholic Monarchs, around 1478 they founded the Spanish Inquisition, which sought the homogenization of Spanish society, by means of brutal force, if necessary. Together they would resume the Reconquest: the campaigns by Christian states to recapture Muslim territories from parts of the Iberian Peninsula.

In 1492 they gained control of Granada from the Islamic Moors, and they ordered all Spanish Jews and later Spanish Muslims to convert to Christianity or face expulsion from Spain. Ferdinand and Isabella’s encouragement of colonial expansion was part of their attempt to increase the power and wealth of Spain.

As part of Columbus’s mission, the monarchs urged him to convert indigenous peoples to Christianity, search for more gold, and develop trading relations. For this endeavor they introduced new rules: settlers received wages, and Columbus was made admiral, with the right to receive one-tenth of all profits as commission. His expedition was equipped with seventeen ships and 1,500 male settlers, including priests. The settlers also brought crops and livestock with them.

Charting a southerly route, Columbus ventured across the Atlantic from the Canary Islands to the Dominica Passage between the islands of Guadeloupe and Dominica. Navigating the Lesser Antilles, he began to observe and remark on the supposed savage and hostile Kalinago occupants.

In 1497 [Columbus] assigned groups of indigenous people to some Spaniards in a system called repartimiento. This saw groups of indigenous people allocated to Spaniards to perform different tasks.

When Columbus finally reached his destination, La Navidad, in 1493—the first Spanish settlement in the Americas forged from the wreckage of the Santa María during his first voyage less than a year earlier—he was shocked by what he saw. The town had burned to the ground, and most of the Spanish settlers were dead, either of disease or in violent disputes about gold with indigenous peoples. The indigenous peoples informed Columbus that they had tried to defend the Europeans against attacks from a rival cacique known as Caonabó, the incident foreshadowing tensions between Spaniards and indigenous peoples that would arise in the coming years.

After leaving La Navidad, Columbus sailed along the north coast of Hispaniola and discovered a new settlement, La Isabela. In April 1494 he resumed exploration of Cuba, inhabiting the southern coast before heading to Jamaica, known by the indigenous peoples as Xaymaca, meaning “land of wood and water.” As Columbus traveled to different islands and interacted with more indigenous peoples, he abandoned the initial plan of establishing trading relations with them. He had a new idea: to force the Taíno to work to develop Spanish colonization. In 1497 he assigned groups of indigenous people to some Spaniards in a system called repartimiento. This saw groups of indigenous people allocated to Spaniards to perform different tasks.

Many indigenous people began to flee their villages to escape from the Spanish. Others chose to rebel. When Columbus instructed settlers to build forts in large towns, Taínos attacked the settlers in large numbers. In 1495 Columbus retaliated by assailing Taíno villages and capturing chiefs. When Caonabó was arrested and sent to La Isabela, a group of chiefs raided Spanish settlements: joining with the indigenous peoples of Guacanagarí and other Taíno allies, Columbus and the Spanish fended off this attack.

That year, Columbus ramped up his assault on dissenting Taínos and sent out armed groups, instructing them to take captives if they encountered any hostility. As a result, around 1,600 Taínos across Hispaniola became captives—of these, 550 were sent to Spain and 650 given to settlers. The majority of the released Taínos fled from La Isabela.

Famine increased in 1495 and 1496 due to some Taíno attacks on Spanish crops, and this further diminished their population, along with increased labor demands and the spread of unfamiliar European-borne diseases against which the Taíno had no immunity, such as smallpox, influenza, malaria, measles, yellow fever, and the bubonic plague. Alongside famine and disease, the fall in the Taíno population was linked to waning fertility rates, partly due to attacks on Taíno villages.

In 1500, the Catholic Monarchs removed Columbus from power in Hispaniola, due partly to disagreements around the treatment of indigenous peoples. In his place, they sent leading Spanish judge Francisco de Bobadilla to govern the colony as viceroy from 1500 to 1502. The monarchs introduced a range of other changes. They granted licences to other explorers and freed all indigenous peoples who had been enslaved and brought to Spain. However, Bobadilla’s rule was to be short-lived: he died two years after being appointed when his ship was hit by a hurricane. His replacement was a military officer, Nicolás de Ovando, who served as governor of the Indies from 1502 to 1509. Ovando arrived in Hispaniola with 2,500 settlers, including Las Casas, and his rule marked a new phase in Spanish–indigenous peoples’ relations.

Ovando was granted enhanced powers in dealing with indigenous peoples, which he took as license to further suppress them. He dismantled a considerable amount of Taíno leadership and introduced the encomienda system to organize forced labor of indigenous peoples to work in mines and agriculture. The encomienda system dealt the Taíno another blow, and as a form of resistance, some died by suicide. More military clashes occurred in 1503 and 1504, and these saw numerous chiefs captured, assigned to Spanish settlers, and compelled to labor in the construction of towns. They were also made to convert to Catholicism.

Alongside increasing assaults on indigenous peoples, the next few years saw mass Spanish expeditions and the establishment of new colonies. In 1508 the Spanish acquired Puerto Rico, the following year Jamaica, and Cuba in 1511. While these islands did have gold deposits, they were not as abundant as had been believed. By around 1508 gold mining had reached its peak, and in later years gold would be in short supply—colonists then turned their attention to sustainable crops that they could sell. This meant drastic alterations in the ecology of the land by clearing the dense rainforest and burning trees for the planting of sugar.

In the early modern era, sugar was a valuable luxurious commodity, replacing honey as a sweetener. The process of developing sugar was long, arduous, and would remain labor-intensive, associated with enslaved labor on large plantations.

The Portuguese were the first to develop sugarcane in Brazil, on Madeira and on the West African coast in São Tomé, using the labor of enslaved Africans from various places. Following them, the Spanish began cultivating sugar in the Canary Islands, which they had begun colonizing in the fifteenth century. The Spanish subjugated and enslaved the indigenous population of the Canaries—the Guanches—exporting some of them to Madeira or Europe, while others were forced to labor on Canarian sugar plantations. The sugar development on Madeira and the Canary Islands would become a model for the growth of sugar in the Caribbean.

In search of more laborers, in 1509 the Spanish Crown granted permission for the forced movement and enslavement of the Lucayans in the Bahamas to Hispaniola, and this was followed by raids in Jamaica, Barbados, and Trinidad. Indigenous peoples resisted these practices. Some began attacking Spanish settlements, and others fled to the mountains. Those who escaped became known as Maroons—runaways involved in the wars with the Spanish in 1519 and 1533. Their guerrilla tactics were effective, and in 1533 the Spanish signed a treaty with their chief leader, Enriquillo, that ended hostilities in exchange for land and freedom.

Coercion and violence were not the only features of indigenous peoples’ interaction with the Spanish, however. Marriages between Taíno women and Spanish men were common, and in 1514 these unions were sanctioned by the Church and state. The offspring of these partnerships shaped the mixed—or mestizo— population. They also helped in the development of creole—meaning “born on the island”—society. But intermarriage could not protect the indigenous peoples, and through wars, disease, and famine their numbers continued to wane. In 1508 there were an estimated sixty thousand Taínos in Hispaniola; by 1514 their numbers had plummeted to around thirty thousand; and by 1518, eleven thousand.

But in another sense, justification for the enslavement of Africans was stark and simple: it served as a way to eke out cheap labor for surplus value from newly claimed territory.

Ascertaining accurate figures for the decrease in indigenous communities in the Caribbean is challenging. While Spanish chroniclers numbered the population around the time of European contact to have been 1 million, anthropologists have disputed this, arguing instead for the population to have been 6–12 million. If these more recent figures are taken as more accurate, they reveal the utter devastation of the indigenous population caused by European contact. Their dwindling population contributed to a labor shortage, which led the Spanish to turn their attention to another group.

By the time the Spanish took an interest in the trade of enslaved Africans, enslavement was already a long-established global institution that operated in various ways. In Africa, men and women could be captured in warfare and enslaved, or taken as part payment for a debt or as punishment for a criminal offense. The Portuguese were an early European power to enslave Africans, doing so with approval in 1452 and 1455 from Pope Nicholas V, who issued papal bulls arguing that slavery provided a Christianizing influence to supposed pagans.

In this era, several justifications were offered for enslaving Africans. Europeans, including Las Casas initially, claimed superiority as Christians, as most of the Africans Europeans encountered were either Muslim or animist. The idea that God used Africans’ black skin color as a mark of their lack of morality and inferiority was another factor (shaped by the biblical curse of Ham and his descendants, who were assumed to be of African descent), as were hierarchical notions of difference that positioned Africans in the lower levels of the “great chain of being.”

Modern notions of “race” did not yet exist, but physical differences and complexion played a role in how Europeans perceived Africans, which would prove precursors to later ideas about whiteness and blackness. For the Spanish, in one sense, the justification for the enslavement of Africans was complex and varied. Some arguments for it relied on religion: the pope had denied Spain land in Africa (based on attempts to limit competition with them and their Portuguese rivals), and many considered enslavement a good way to convert those considered pagans or who shared different faiths to Christianity. But in another sense, justification for the enslavement of Africans was stark and simple: it served as a way to eke out cheap labor for surplus value from newly claimed territory.

Enslaved Africans were initially only a small part of Spanish colonization in the Caribbean. The Spanish did not have any forts on the African coast, so they depended on other states, like Portugal, to supply them with enslaved people. The first enslaved Africans began to arrive in the 1500s and were ordered by King Ferdinand to work alongside indigenous peoples to build forts in gold mines.

In 1502 Ovando brought over more enslaved Africans, but many escaped and found refuge with indigenous peoples who had fled to the mountains. From 1518, a new series of contracts—the asiento de negros—began, which allowed private figures to transport enslaved Africans on the condition of paying a fee to the royal treasury. It was believed that Africans could withstand the tropical climate of the Caribbean and were more resistant to disease than the Taíno, and this helped spread the stereotype that enslaved Africans were physically stronger workers. In the mid-sixteenth century, the enslaved African population of Hispaniola was around thirty thousand; by the end of the century their number in the Spanish Caribbean had grown to about one hundred thousand.

The use of enslaved labor was critical to the success of Spanish colonialism in the Caribbean, but the islands were just the first stage of a period of conquest during which the Spanish Empire expanded to include Florida, Mexico, Panama, Cartagena, and Peru.

Crucially, however, the Spanish did not extend their reach into the Eastern Caribbean, for reasons still debated today. One argument is that these areas did not have the resources the Spanish sought to accumulate, while another casts the Kalinago as more difficult to subdue than the Taíno. Nevertheless, the Eastern Caribbean became a place of refuge for both indigenous peoples and enslaved Africans who had escaped from Spanish territories. It would soon also become a space for the arrival of new colonial powers who, having heard stories of successful Spanish exploits in the region, were eager to see if they too could prosper in the New World.

Attempts to shatter the Spanish monopoly in the Caribbean accelerated in the 1540s. The French started to plunder Spanish ships on their voyages to Spain, and the English quickly joined in—their attacks shaped, in part, by the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century, which spawned anti-Catholic and anti-Spanish sentiment. In 1572, Queen Elizabeth I sent English troops to help the Dutch win back independence from Spain and continued encouraging privateers—effectively pirates with a royal license to plunder—to attack Spanish ships. As the Spanish hold over the Caribbean Sea weakened in the 1560s, English voyages to the region increased.

Naval commander, administrator, and buccaneer John Hawkins led an early English expedition to the Caribbean around 1562, taking three ships via what is today Sierra Leone. On their way, he and his crew attacked a Portuguese ship, captured the enslaved people on board, and traded them in the Caribbean, making a profit for the London merchants who had invested in the expedition. With the approval of Elizabeth I, and with his second cousin and protégé Francis Drake in tow, Hawkins continued privateering, traveling to the West African coast, where he purchased more enslaved Africans to trade in the Spanish Americas. In response, the Spanish attacked his ships.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Empire Without End: A New History of Britain and the Caribbean by Imaobong Umoren. Copyright © 2025 by Imaobong Umoren. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

Imaobong Umoren

Imaobong Umoren is a historian of racism, women and gender in the Caribbean, Britain, and wider African diaspora. She is an Associate Professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science.