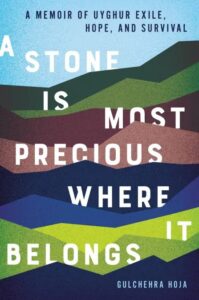

How China’s Uyghurs Are Marginalized and Subjugated by the State

Gulchehra Hoja Recounts Her Harrowing Experience at the Hands of Xinjiang Police

For most Uyghurs in our homeland, the late 1980s and 1990s brought both an economic boom to the region and catastrophic unemployment. This might seem conflicting, but underlying that growth were Han-run companies and Han-run government projects, and very little of the wealth that was generated trickled out into the Uyghur community.

Instead of hiring Uyghurs, bosses would bring in Han workers from China to work on construction crews, energy industry projects, and road building. There were communication problems, because almost none of the Han migrants to East Turkestan spoke Uyghur, and also outright discrimination, because many Han viewed Uyghurs as lazy or unwilling to take orders from a Han boss. As a result, even Uyghur college graduates—some of our best and brightest—had trouble finding work in Ürümchi.

In the meantime, the Han population exploded. By the year 2000, the Han constituted more than 40 percent of the nearly 18.5 million people in East Turkestan. Uyghurs found themselves increasingly marginalized in their own land, especially in the northern and northeastern regions, where Ürümchi is located, and where the Han population was concentrated.

On the pleasant, tree-lined campus of Xinjiang Normal University, I felt relatively insulated from the outside world. Because my family was educated and relatively well-off, and highly respected within the community, I proceeded along under the assumption that my generation would grow up to be successful, independent adults, as our parents had before us.

My cousin had already made something of himself and was working in the government as the deputy chief of staff for the district head of the Saybagh District of the city of Ürümchi. He had a fair amount of power and influence locally, and he always had time to help us with any little bureaucratic issues that came up, such as getting the proper documentation to do anything, from changing an address to enrolling in a new school.

But none of his connections nor those of anyone else in our family protected us from the larger political and social forces operating within China. When I was in my third year of college, something happened that shattered my relative innocence, something that remains a deep scar in my life and that heralded worse things to come.

Uyghurs found themselves increasingly marginalized in their own land.It was New Year’s 1993. My younger brother was nineteen and a student at the prestigious Xinjiang Medical College, studying to become a doctor. I was in my third year at Xinjiang Normal University. That night, we were both planning to go out for New Year’s Eve, and the house was filled with activity and pleasant anticipation. I was meeting Mehray to go to a party on campus with her. She was so lovely and vivacious that before long I knew we’d have every boy in the room hoping to dance near us.

Kaisar stuck his head into my room just before dinner. He riffled my hair teasingly and asked me if I would iron his clothes. “Come on, Gul,” he pleaded. “I need these for the party tonight, but there’s something I have to take care of first. You want your brother to look his best, don’t you?”

I laughed and agreed to iron his clothes yet again. He was right—I was proud of my handsome little brother, and if he did the ironing the creases would just get worse. He’d grown up to be tall and fit, with a head of thick black hair and eyes that danced when he smiled. But he still liked to pinch my cheek and muss my carefully combed hairdo just as he used to do when we were kids.

“Where are you off to?” our mom called from the kitchen. “I’m cooking. Stay and have a good meal before you go off carousing.”

“I’ll be back soon. Don’t let them eat everything before I get back!” He gave her a loving pat on the cheek and was gone.

I spent the afternoon ironing our outfits, putting on my makeup, choosing and re-choosing my dress, making sure I looked perfect. My brother hadn’t come back, so I took a quick catnap. Our parties always started late in the evening and didn’t end until the next morning, with people singing and dancing to music that went all night.

I had just finished dressing when there was a pounding on the front door. My heart leapt into my throat. No one ever knocked on the door like that. My father was in his study and my mother was still in the kitchen cooking a big meal to celebrate the new year, so I went to the door.

When I opened it, three policemen were standing there: two Han and one Uyghur. The Uyghur officer was familiar from around the neighborhood, but I’d never seen the two Han policemen before. Instantly, my hands started to sweat. We tried to avoid Han policemen as much as possible because they were generally known for their ruthlessness when dealing with Uyghurs. Something serious had to have happened for them to show up at our house.

“Does a Kaisar Keyum live here?” one of the Han officers said, his tone sharp. He tried to push me aside, but I held my ground.

My father rushed out of his study. “What’s going on?”

The policeman showed him a piece of paper. “We have a warrant to search Kaisar’s room. Show me where it is.”

I was confused. My brother had left just a few hours before; he should be back any minute. My mind was racing with possibilities—he must be hurt, a car accident, a fire….

“He’s in big trouble,” the officer said. “You have to let us in.”

“What’s happened?” my father said. “Tell me what’s going on, and then I’ll show you his room.”

One of the Han policeman stuck his face close to my father’s. “You have no idea how much trouble your boy has caused. Your whole family is under suspicion. Do you understand me? Just show me his room.”

Shaking, but not willing to back down, I put my hand up and demanded, “Let me see the warrant. And where are your police badges? How do we know you are who you say you are?” I was terrified, but I was determined not to simply capitulate through fear.

None of his connections nor those of anyone else in our family protected us from the larger political and social forces operating within China.The Uyghur policeman stepped forward. He was a young man with a gentler expression than the others. He said, “Miss, please. Just be cooperative. This is a very serious situation. You’re going to have to let us in.”

Suddenly, one of the other policemen grabbed the hand that I had held up. “That ring,” he said roughly, pulling at my finger. “Did your brother give it to you?”

“Of course not! It’s my grandmother’s ring. An heirloom.” I was beginning to grasp that something was terribly wrong. I moved out of the doorway and the police pushed their way inside.

They searched the house, collecting things from my brother’s room and shoving them into plastic bags. My father followed them around protesting, while my mother and I huddled together against the wall. Then one of the policemen pulled out a small stack of money from a drawer. Another policeman was at the closet, throwing brand new clothes that we’d never seen before on the floor. My mother and I looked at each other, stunned. What was this stuff doing in our house? The policemen took it all, along with Kaisar’s photo albums and even a few books.

As they were leaving, one of the policemen ordered us brusquely,

“Come to the station tomorrow.”

My mother caught the Uyghur policeman at the door and begged him, “Please, tell me what’s happening. At least tell me where my boy is.”

He shook his head. “I can’t say anything yet. He’s still being questioned. But your son was involved in a burglary. They think it has to do with drugs.”

My mother leaned against the door as it closed, her face pale. “This is all a mistake! They’ve gotten our Kaisar mixed up with someone else. He’s the best student in his class, how can he be involved in anything like that?”

That evening was a nightmare. Of course, no one went to any parties, and the food my mother had so lovingly prepared turned cold on the table. Despite the late hour, my father started calling all his friends with connections, but nobody had any information. We went to bed silently well before midnight, having no idea what had happened.

The next day my father, mother, and I went to the police station. They wouldn’t let us see Kaisar or even tell us if he was there. But we did learn that he’d been arrested along with four other students at the Medical College. They were accused of breaking into the Ürümchi police chief’s house, a prominent Uyghur in the community, and stealing thirty kilograms of gold from his cupboard. No one asked what the police chief was doing with thirty kilos of gold in his kitchen.

The chief had ordered the houses of all five boys searched. At the same time, the police told us, they assumed that given the boldness of the crime, drugs were sure to be involved. If they were, the burglars would have to sell the gold in order to get cash to buy drugs. So they’d stationed Uyghur policemen in the Uyghur gold stores around town, where they’d found my brother trying to hawk some bars of gold and had arrested him.

The fact that Kaisar was Uyghur meant that he was subject to the worst treatment.We left the station completely at a loss. Nothing the police told us fit with what we knew of my brother, or his friends. None of it made sense. Why would five medical students from well-to-do families break into the house of the Ürümchi police chief? It would have been farcical had it not been so frightening.

My brother was tortured for three days in the police station. He was hung by his arms from chains and beaten. When he refused to confess or name any accomplices, they just beat him harder. Suspects aren’t treated well anywhere in China—if you’re arrested, you’re considered guilty unless proven innocent—but the fact that Kaisar was Uyghur meant that he was subject to the worst treatment. The police had no fear of any repercussions for brutality or neglect; they had the full force of the CCP behind them. They knew it, and we knew it too. We didn’t learn the details of his detainment until later, but we had our fears.

When we got home, we ransacked the house, looking for every bit of cash we had. We called our relatives to see what we could borrow from them too. We collected 10,000 yuan, a sizable sum of money, within a day or two. We thought it might serve as some kind of restitution.

My mother wrapped the cash up in a scarf and put it in her purse. She went to the police chief’s house and knocked on the door. When he came to the door, she held the money out to him with both hands. “I’m Kaisar Keyum’s mother. Please, he’s my only son,” she begged. “He’s done something wrong, but please be lenient with him. Just give him a chance to finish school. I can swear we’ll never let anything like this happen again.”

The police chief was a large Uyghur man with a pronounced belly and a thick gold watch on his wrist, the very image of a good comrade. He towered over my mother. He brushed away the stack of money contemptuously. “You’re lucky I didn’t shoot your son when I had the chance. He’s a fast runner, but he’s not going to get out of this one.”

On her way home from the police chief’s house, my mother had a mild heart attack and collapsed on the street. She ended up spending the night in the hospital. My father and I anxiously sat by her bedside all night. I think that was the day her heart broke.

__________________________________

Excerpted from A Stone is Most Precious Where it Belongs: A Memoir of Uyghur Exile, Hope, and Survival by Gulchehra Hoja. Copyright © 2023. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.