How Campus Novels Reveal the Power—and Danger—of Pure Ideas

Tara Isabella Burton on the Combination of Isolation, Vulnerability, and Hunger for Knowledge

Every few years, I go through entries of my now-defunct Livejournal: a journaling website I used with obsessive regularity throughout my teenage and college years. Invariably, my attention turns to my earliest entries on the platform; largely written during the three years I spent in somewhat feral isolation at a red-brick, ivy-trellised boarding school in New Hampshire. They are, of course, what we might now call cringe: agonizingly earnest, intellectually rapacious, emotionally overrwrought. But they are also, in their way, beautiful.

Back then, I believed that everything I ever learned in class applied directly, and exactly, to the life I would one day live. I would write thousands of words after Latin class, meditating on whether I was more like pious, self-controlled Aeneas or the passionate Dido: her heart constantly aflame. (The answer was, naturally, the latter, although I often wished I could develop the capacities of the former). I would write about reading Antony and Cleopatra in my senior Shakespeare seminar, and wonder aloud—to a “friendslocked” audience of ten or twenty strangers—whether all human relationships demanded performative artificiality.

My emotional life and my academic life were intertwined, as they had never been before, and never would be thereafter: in college, in grad school, in adulthood. What I read—whether in class or sequestered away on my school library’s third-floor mezzanine, sufficiently ill-attended that it doubled as an infamous campus hookup joint—mattered to me. And I believed, with childish conviction, that books—and only books—could teach me how to live. I remember once patiently explaining to a classmate that I planned to spend my semester working on an erotic novel set in fin de siècle Paris.

They asked me how I could write an erotic novel when I was—quite obviously—a total virgin.

This did not deter me.

“Well,” I continued, “I’ve read a lot of of Anaïs Nin.”

Granted, even by the standards of teenagers, I was particularly bereft of self-awareness. I was an awkward teenager, invariably an insufferable one. I had been homeschooled for much of the previous two years, moving halfway across the world and then back again with an itinerant mother. Much of my eighth grade year had been spent riding my bicycle unsupervised through the streets of Rome, doing my makeshift Latin homework in the forum. Flesh-and-blood people confused me. They did not operate with the same purity of intention that the characters I loved most did; they were not gloriously elemental—like Oscar Wilde’s seductive Henry Wotton, say, or the desperately saintly Alyosha in The Brothers Karamazov—but uncertain and self-contradictory.

But when I think back to those three years I spent in New Hampshire, what strikes me most is how widespread this tendency was. All of us—nearly all academically gifted, absolutely all emotionally immature—took the conversations we had in class with utmost, credulous seriousness. We believed that because we were clever, and good at school, and good at reading, that we could somehow skip ahead past the messy bits of our own adolescence. We could learn what a good life looked like without ever needing to actually live. We would corner one another at the dining-hall, in order to share unsolicited advice about how our peers could better develop social graces.

We would take notes in history class about whether it was better to emulate someone like Klemens von Metternich—the consummate conservative, wary of the bloody consequences of political change—or the scheming Otto von Bismarck, whose flint-eyed realpolitik lent itself neatly to the social vagaries of the dormitory status hierarchy.

As in a fairy-tale—where parents are often conveniently absent—the campus novel uproots voracious, capacious young people from their ordinary settings.

Much of this, of course, seems nightmarish in retrospect—and I cannot say my years at Phillips Exeter were particularly happy. But the geographic isolation of a small New England campus, combined with our shared conviction in the relevance of our intellectual pursuits, rendered us collectively, and wonderfully, vulnerable. For the first time in my life, we were in a place where ideas mattered; where what we read we read not in pursuit of academic laurels, nor in college acceptances, but rather of genuine answers to the questions whose relevance teenagers, in particular, feel most keenly: who am I supposed to be? How do I live? What does it mean to love a person, or to want a person—and are they the same thing?

It is precisely that sense of both isolation and vulnerability that makes me particularly susceptible to the campus novel, and in particular the campus bildungsroman: a genre that, at its best, explores the concentrated effects of extreme ideas on receptive human beings. As in a fairy-tale—where parents are often conveniently absent—the campus novel uproots voracious, capacious young people from their ordinary settings. Their friends, their families, their before-life are often elided from the narrative entirely; we are left, rather, with characters who both hunger for knowledge and lack the self-protection that would make it possible to take that knowledge less seriously.

Even interpersonal relationships—of love, of lust, of grudging respect or enmity—are inextricable from this hunger for ideas, for certainty in the world; there’s a reason that a standard trope of the campus novel, from Evelyn Waugh’s 1946 Brideshead Revisited to Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie to Donna Tartt’s 1992 The Secret History is the mysterious “chosen set”: students set apart by perceived intellectual or spiritual or aesthetic superiority, who induct the protagonist into a world of both interpersonal tensions and, ultimately, interior knowledge.

In Evelyn Waugh’s 1946 Brideshead Revisited, for example, which takes place largely in 1930’s Oxford, the protagonist, Charles Ryder, comes to an uneasy Catholicism through his homoerotic relationship with the aristocratic dandy Sebastian Flyte. In The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, also set in the 1930’s, the titular teacher indoctrinates her favored students (including our protagonist Sandie) into a passionate worship of romantic strength and power that culminates in fascist sympathies. And in The Secret History (about which I’ve recently written in more detail), narrator Richard Papen’s corruption comes through his election into an elite campus Greek reading group: his moral corrosion, which leads him and his new friends to murder and madness, explicitly linked to the seriousness with which the characters take the brutality of Greek tragedy as a serious model for understanding the world around them.

At their best, these books reveal to us two truths: truths I intuited, but did not fully understand, during my own time at boarding school. They reveal the sheer power—and danger—of pure ideas, unadulterated by the compromises maturity often demands: what does it look like, these novels ask, to take anything too seriously? They reminds us that ideas are not just playthings—conceits to bandy about at cocktail parties, or espouse for clout on Twitter—but rather the fundamental building blocks of human life: integral to how we actually live. But they reveal, too, the way in which our love of ideas and our love of other people are inseparable from one another.

Consider the way in which, for example, Charles and Sebastian’s relationship is both the story of two men falling in some confusing kind of love love—a love that leads Charles in turn to faith; and also the story about how Charles’s love of beauty, and his pursuit of something more than the bourgeois existence his class background seems to consign him to, makes him particularly susceptible to someone as alluring—and as emotionally disastrous—as Sebastian proves to be. The best campus bildungsromans are those that at once take ideas seriously and also help us understand how our own relationships—of love, envy, and desire —are never as divorced from our hunger for knowledge, of both the self and the world.

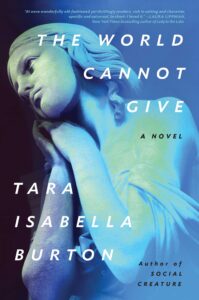

In my own forthcoming novel, The World Cannot Give—at once an homage to, and a subversion of—the classic campus bildungsroman, I tried to capture something of my own boarding school experience. I tried to capture the astounding awkwardness of loving too much, of loving too deeply, of falling in love with books and people alike and never quite being sure where the one ends and the other begins. And, perhaps more than anything else, I tried to capture that heady sense—so familiar to my sixteen-year-old self—that the love we have for one another, and the love we have for what we read and learn, all perhaps come from the same place. That what we hunger for, in the books and the people who break us open, is at once to understand and to be understood: to make sense of a world that feels, in adulthood no less than at sixteen, too big, too wild, and too wonderful for us to ever fully grasp.

__________________________________________________

Tara Isabella Burton’s The World Cannot Give is available now via Simon & Schuster.

Tara Isabella Burton

Tara Isabella Burton is a contributing editor at the American Interest, a columnist at Religion News Service, and the former staff religion reporter at Vox.com. She has written on religion and secularism for National Geographic, the Washington Post, the New York Times, and more, and holds a doctorate in theology from Oxford. She is also the author of the novel Social Creature (Doubleday, 2018).