How Cairo Became a Cosmopolitan Destination in the 1920s

Raphael Cormack on Egypt's Interwar Nightlife Boom

“Egypt is a country where the Egyptians reign, English rule, and everybody does as he pleases.” So two African American residents of Ezbekiyya wrote in a letter of December 1923, published in the American newspaper The Chicago Defender. The pair were Billy Brooks and George Duncan, two international jazz musicians who were thriving in Cairo’s 1920s nightlife. The city was coming into its golden age, part of the great international roaring twenties. After the First World War many people, fleeing a destroyed Europe, wound up looking for opportunity in Cairo. And many of them found their way to Ezbekiyya.

The dance halls swelled with women fleeing the economic collapse and political repression in Eastern Europe. Many who found work in cabarets were Hungarian; so much so that the cliché of Hungarian chorus girls became a fixture of interwar Cairo, even if many of them were not from Hungary. Life was often difficult for these women. It was hard enough being an average local Egyptian dancer, but new arrivals did not know the city or how it worked. Living in bedsits or boardinghouses, many women struggled in their new lives. In 1932, one dancer took a large quantity of drugs and fell—or, as many assumed, jumped—from her balcony. Only a few managed find a comfortable place for themselves in Cairo. The most famous was Dinah Lyska, an Eastern European dancer and singer who won celebrity by dancing and singing in the Franco-Arab revues of the early 1920s. She eventually left the stage behind and opened the Bar Lyska on Emad al-Din Street.

In December 1922, the world’s press announced the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb and a flurry of excitement soon followed. By spring 1923, women in Paris were wearing Tutankhamen hats. Two film companies, one in Los Angeles and the other in Prague, had announced they were working on a Tutankhamen film. In London’s West End, designers modelled their new dresses on discoveries from the tomb, and in America a handbag company had already applied to trademark the name Tut-Ankh-Amen. Egypt was all over the front pages, and Cairo’s residents must have felt they were living at the centre of the world.

Billy Brooks and George Duncan had taken a circuitous route to end up in Cairo. Born in the American South in the days of slavery, the men had left the United States from New York Harbour in early August 1878. They went with sixty other African Americans to perform with Jarrett and Palmer’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin minstrel show, and they never looked back. This touring dramatic version of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, featuring song-and-dance numbers by a “host of genuine freed slaves,” opened in London in September and then travelled across Europe. Instead of returning home with the troupe, Brooks and Duncan decided to cash in their return tickets and try their luck on their own.

Over the next few decades, the pair became part of a burgeoning global African American performance scene in Europe, meeting with both success and danger as well as predictable racism (in Belgium they were given twenty dollars to play music on bones and tambourines in a cage with five fully grown lions. They left after the first night, happy to escape with their lives). Eventually, in 1914 they wound up in Egypt and decided to settle down. In the early ’20s, by then veteran performers, they set up a small group called the Devil’s Jazz Band. At first, they recruited four Greek musicians to play alongside them. From the start, though, the band’s line-up was flexible, and in its varying forms it demonstrated the variety of people working on Emad al-Din Street after the First World War.

At different times the group included a Russian-Jewish pianist, who played the piano so lightly that “if you did not look his way at times you would not know that he was touching the keys”; an Egyptian-born Polish-Jewish banjo player who “doesn’t thump the ’jo badly”; a well-trained Greek trombonist; and a Russian woman on the drums, who made her own “thunder and lightning effects” at the back of the stage. In their letters Brooks and Duncan commented, archly, that “she certainly makes the big drum sweat.” They once hired a local Egyptian drummer who had been to the Cairo branch of London’s famous Ciro’s club, where the American drummer Seth Jones, another of many travelling jazz musicians of the 1920s, led the band. Brooks and Duncan rather liked their Egyptian percussionist, who they said “caught onto the jazz stuff pretty well.”

After the First World War many people, fleeing a destroyed Europe, wound up looking for opportunity in Cairo. And many of them found their way to Ezbekiyya.

After nearly a decade in Cairo, Brooks and Duncan were not even at the top of the local jazz scene. Besides the many Europeans and few Egyptians playing in the country, at least ten African American or West Indian jazz musicians were working between Cairo and Alexandria. The most successful performer in the early 1920s was Billy Farrell, another African American, whose career began in the late nineteenth century with a minstrel show and who was now making good money playing jazz for foreign tourists in expensive hotels. Brooks and Duncan were not on the hotel circuit. They played in dance halls and what they called music palaces. These haunts were frequented by local Egyptians, not wealthy travellers, from the reasonably upmarket Kursaal on Emad al-Din Street down to Ezbekiyya’s less salubrious venues where the dancing could continue until dawn.

By their account, Cairo in the ’20s was a great place for a couple of African American musicians. They were relieved to have escaped the racial segregation of turn-of-the-century America—as well as the dangerous “circus” acts of Europe—and they were going to enjoy themselves in Cairo while they could. The pair sent letters to the Chicago Defender telling readers about the fun and freedom they had found. In particular, they loved recounting their occasional meetings with white American tourists, particularly those who asked why they didn’t want to return to America:

It seems to be a wheeze which they have learned by heart to say: “I know the reason why you don’t go back is because you are having a good time over here.”

We generally answer: “Why should I not have a good time here, in a black man’s country? You have a good time in America, which you call a white man’s country. Here we are on the same plank as you. If anything happens and we have to say “Good Morning Judge,” we have a square deal at the cards when it is our turn to deal.”

In the midst of Cairo’s growing cosmopolitanism, Egypt was going through an uncertain political period in the aftermath of a revolution. It was exciting and potentially liberating but also tense and dangerous. The country now had nominal independence; the sultanate had been abolished and replaced with a king. The previous monarch, Hussein Kamel, had died and been replaced with yet another of Khedive Ismail’s sons, Fouad. Parliamentary politics, which had existed before, had new power and meaning in the new country.

At the beginning of 1924, the people awaited the first election results. Saad Zaghloul, the hero of the 1919 revolution, won in an expected landslide; his Wafd Party had taken almost 90 percent of the seats. At the end of January, he was named prime minister and declared his continuing commitment to Egypt’s total independence. In just a few years, Zaghloul had gone through imprisonment and exile to become the popular leader of a rising nation.

In the midst of Cairo’s growing cosmopolitanism, Egypt was going through an uncertain political period in the aftermath of a revolution.

For Egyptian women, the victory was bittersweet—they were left out of the new political process, denied the right to stand for election or even to vote. When a list of invitees for the new parliament’s opening ceremony was released and no Egyptian women were included, it was the final straw. Two weeks before the event, Mounira Thabet, a young woman just out of high school, wrote an open letter to Egypt’s main Arabic newspaper, al-Ahram. She would later get a law degree in France and become one of Egypt’s most prominent feminist voices, but in her letter she identified herself simply as a “woman demanding the right to vote.” She told the paper’s readership, “Women had no less a role in the struggle than men did so it is her right—rightfully, morally, and legally—to be a part of the opening ceremony of the parliament which is the fruit of this shared struggle. You have deprived us of our right to become elected members of this parliament, will we not even get to take part in the opening ceremony in compensation for this treachery?”

On March 15, the day of the opening ceremony, a group of female students stood outside the parliament’s gate holding protest signs. Half the signs made general political demands, such as the withdrawal of the British army, the right to free association, and the unity of Egypt and Sudan. The other half made appeals to specifically feminist concerns: the right of women to vote, equality of the sexes in education, and a limit to the number of wives a man could have. Public statements stressed how betrayed the women felt after sacrificing so much in the fight for independence and then had not seen the benefits they expected. The Wafdist Women’s Central Committee, chaired by Hoda Shaarawi—heroine of the women’s march in 1919—sent a telegram to the president and the local press. It was a reminder that women, “as half of the nation, . . . took part in the struggles and sacrifices that led to the independence of their country,” and that excluding all women from the opening ceremony was “an undignified act.” The newspapers supported the women, but their demands were not realized.

In the exclusively male world of Egyptian politics, the 1920s and 1930s were full of intrigue and political fights: new parties were formed, others split, and power struggles were waged. Saad Zaghloul and his Wafd Party, unsatisfied with the litany of qualifications the British had put on Egypt’s sovereignty, continued the campaign for genuine independence. Several other parties competed for power against Zaghloul’s. The main competitor was the Liberal-Constitutional Party, which had emerged partly to call attention to Saad Zaghloul’s dominance of the Wafd Party. Liberal-Constitutionalists promoted a gradualist approach towards complete independence that focused on peaceful negotiations with the British. Besides these two major political groups, the Union Party rose up, largely to support the king and the policies of the palace. Meanwhile, prime ministers came and went; very few of them lasted a year. In the early 1930s an entirely new constitution was written, only to be abandoned a few years later.

On paper, the Egyptians were no longer ruled by Britain. But the British had certainly not gone away: They were keen to maintain their interests in Sudan and around the Suez Canal and kept a significant military presence in the country as well as control in state institutions like the police force, where many senior figures remained British. Egyptians could be forgiven for wondering why their former occupier still exerted so much control in the country.

The political landscape in the interwar period was enormously complex. It is usually explained as a competition between three poles: Parliament, the king, and the British, each working to build its own power both publicly and behind the scenes. Parliament relied on its popular legitimacy, the king used his wide constitutional powers (like appointing the prime minster), and the British applied a mix of force and subterfuge. But these three also had to contend with shifting allegiances, personal feuds, and outside actors. Egypt’s new “liberal age” was a convoluted mixture of ideologies, influences, and interests.

The political landscape in the interwar period was enormously complex. It is usually explained as a competition between three poles.

It was also a violent time. A network of secret societies with ominous names like the Black Hand or the Revenge Society organised violent attacks and assassinations, usually against British targets. The spate of bombings and shootings reached its peak in 1924 when the British governor-general of Sudan, Lee Stack, was assassinated in Cairo. This incident had far-reaching consequences: The culprits were arrested and executed, but the British, demanding further retribution, used the incident as a way to reassert power. They thought Saad Zaghloul and his Wafd Party, with their strident anti-British views, bore some responsibility for the crime. An internal telegram between British officials claimed that the “spirit of indiscipline and hatred which Egyptian Government have incited by public speeches and through activities of their Wafd cannot but be regarded as contributory to the crime.”7 On 24 November, just five days after Stack’s assassination, the crisis was so severe that Saad Zaghloul resigned as prime minister and would never again hold the office. He died in August 1927, suffering the effects of a separate assassination attempt directed at him in the summer of 1924.

It is hard to know exactly how much people would have followed every step of Egypt’s political turmoil. When looking at the entertainment scene, however, it is at least important to keep in mind the larger picture of a newly instituted democracy accompanied by power wrangling, rising nationalism, and continuing anti-colonial struggle.

__________________________________

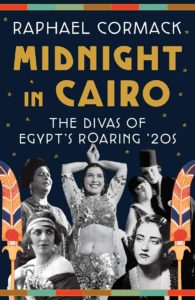

Excerpted from Midnight in Cairo: The Divas of Egypt’s Roaring ’20s. Copyright© 2021 by Raphael Cormack. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Raphael Cormack

Raphael Cormack is an award-winning editor, translator, and writer. The author of Midnight in Cairo, Cormack is assistant professor of modern languages and cultures at Durham University in the United Kingdom.