How Beth Brant Uplifted the Voices of Native American Queer Women

On Taking a More Inclusive Approach to Indigenous Writing

Bay of Quinte Mohawk writer Beth Brant (Degonwadonti) was born in her grandparents’ house in Detroit, Michigan, in the year 1941. Her parents were Joseph Brant (Mohawk) and Hazel Brant (Scots-Irish). Pregnant at 17, Beth Brant married when she was 18 and, in the ensuing years, had three daughters. In 1973, after 14 years of marriage, she divorced and became a single mom, settling in Melvindale, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit, where she supported herself and her children through a variety of odd jobs—waitress, salesclerk, cleaning woman. Beth acknowledged that she had felt an attraction to her close girlfriends when she was teenager. Later, as various liberation movements flowered in the 1960s and 70s, she claimed her lesbian identity. In 1976 or 77 she became partners with Denise Dorsz, the co-founder of a feminist coffee house in Detroit that opened in 1971, Poor Woman’s Paradise. They were partners for over 20 years.

Beth began writing in 1981, at the age of 40, and she considered her words a gift from the spirit world. The small outpouring of her work includes essays, short stories, and poetry. At the urging of Adrienne Rich and Michelle Cliff, who were co-editing the lesbian art and literature journal Sinister Wisdom at the time, Beth served as the guest editor of a volume of Native American women’s writing: A Gathering of Spirit, published by Sinister Wisdom (1983) and later reissued by Nancy Bereano’s Firebrand Books (1988).

This volume for Sinister Wisdom emerged from a conversation Beth had with Michelle and Adrienne when they were living in Massachusetts. On a snowy evening in January 1982, Beth, as a guest at their house, asked Michelle and Adrienne if they had ever considered devoting an issue of Sinister Wisdom to Native women’s writing. When they suggested that she could edit such a collection, Beth was taken aback, worrying that she would not be up for the task, lacking, as she did, a high school diploma, let alone a college degree. Yet through this work and her further writing, Beth developed a passionate voice. She became well-known among Native American and First Nations writers, other women of color writers and poets, many of whom were lesbian, and the world at large.

Sinister Wisdom 22/23: A Gathering of Spirit was not the first anthology of contemporary Native American writing to be published in the United States. A decade earlier saw the publication of The Man to Send Rain Clouds: Contemporary Stories by American Indians (1974), edited by Kenneth Rosen and featuring writers like Leslie Silko, Simon Ortiz, Anna Lee Walters, and other Indian writers who were primarily associated with the Southwest, with the University of New Mexico, or with the Santa Fe Indian School and the Institute of American Indian Art (IAIA) in Santa Fe. A year later, Rosen’s Voices of the Rainbow: Contemporary Poetry by Native Americans, included Silko and Walters, as well as poets Gerald Vizenor, Carter Revard, Anita Endrezze (Probst), Ray Young Bear, and others. In 1979, the University of New Mexico Press published The Remembered Earth: An Anthology of Native American Literature, a more comprehensive volume of writing edited by Geary Hobson. Perhaps the most prominent among these contemporary voices was N. Scott Momaday, whose novel House Made of Dawn won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969, and ushered in a renewed interest in American Indian writing among non-Native academics and others. Many of the writers involved with these works had already published stellar volumes of poetry, short stories, and novels—or would go on to do so in the next few years. These and other books by American Indian writers helped set the stage for the writing that appeared in A Gathering of Spirit and Beth’s other works.

Beth wanted to include the voices that would not typically find a place in American letters.

However, it was not Native American publishing alone that helped to create a place for Beth’s writing to appear. A nexus of social changes (including American Indian activism), a revisionist impulse in the writing of American history vis-à-vis American Indians, and the emergence of Ethnic Studies and Native American Studies, specifically at the university level, helped augment public interest in Indigenous American writing. The inclusion of American Indian literature in some English departments and women’s studies programs also served to make a space for Native writers, some of whom, like Silko, Welch, Harjo, Momaday, and Vizenor, eventually became canonical.

Neither American Indian writing in the 1970s nor the writing that came into flower in the 1980s—much of which was produced by women—would have found as wide an audience without the development in the 1970s of small presses. These presses offered a voice and support to women writers (including white lesbians, lesbians of color, and working class gay and straight women) and facilitated the rise of independent women’s publishing enterprises and bookstores.

From Shameless Hussy Press, founded in 1969 and billed as the first feminist press in the United States, to the Women’s Press Collective in Oakland, California, to a plethora of other women’s, lesbian, working class, people of color, and leftwing publishing venues, an explosion of printed matter became available. One aim of this grassroots publishing was to “raise consciousness,” as it was termed, and provide information on social justice issues, including women’s access to health and education, and the question of female exclusion from positions of political power and authority. Much of the collective activity and writing that began to emerge from this ferment was consciously anti-racist and anti-homophobic. It questioned and challenged the multiple social oppressions operating through a corporate-capitalist-colonialist, patriarchal system that virtually ensured women’s erasure and could violently coerce women’s silence. A significant part of this discourse was coming from women of color, whether lesbian or straight.

When This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, erupted in feminist circles in 1981, it became a primary text for feminist writers and thinkers of color. I would guess that a space opened up for Beth that allowed her to imagine “weaving together” a volume of writing that she believed was “urgent.” It would be comprised of “physical details . . . spiritual labor . . . ritual . . . gathering . . . [and] making.” She saw her editing as an “unraveling” of the cloth that brought these American Indian women writers together, but also as a weaving that could stitch the threads, “each one with its distinct color and texture,” into a new cloth made of this spirit-gathering. In this sense, it parallels the vision of This Bridge that was a platform for a sisterhood comprised of “Sisters of the yam Sisters of the rice Sisters of the corn Sisters of the plantain,” as Toni Cade Bambara explains in the Foreword to that volume’s First Edition. But Beth’s perception of her work, as she conceived of it in her Introduction, was quieter and less consciously a call to action (though no less radical) than Bambara’s serious-playful dialoguing. In her Introduction, Beth’s syntax is precise, and for a woman who called herself “uneducated,” this seems a pointed and important decision.

What likely interests readers is how Beth constructs a Native identity through accessible language of caring and compassion.

Beth was aware of how crucial the job was of selecting and arranging the work submitted for A Gathering of Spirit, as well as the way she created a context for understanding and appreciating it. She wanted to do justice to the work she had gathered, to clarify its significance—and just as critically, to show the ritual of its inception and birth, to highlight its strength and beauty, to make a space for the anger, despair, and desperation that she opened herself to by editing this volume. She understood that part of her task was to connect with the writers who sent her their work—along with their queries and questions that were not always about writing—and to connect those writers together. A Gathering of Spirit is a unique creation in many ways. Beth wanted to include the voices that would not ordinarily be heard, that would not typically find a place in American letters—those voices of prison inmates, of women living on reservations or in Indian enclaves in big cities, the voices of single, sometimes lesbian mothers, of women who engaged in physical labor to make a living and support a family.

While Beth selected writing by Indian women who were to become or were already a part of the academic world, she was democratic and non-canonical in her choices for A Gathering of Spirit. Just as important to the volume is the imaginative work, and “erotics,” of gay Native women. As literary critic Lisa Tatonetti points out in her essay, “The Emergence and Importance of Queer American Indian Literatures . . .,” Beth’s anthology is “[n]otable on a number of levels, [it being] the first collection of American Indian writing to be edited exclusively by an American Indian. In addition, its importance to the development of queer Native literature cannot be overrated as the anthology includes pieces by eleven Native lesbians….” The inclusion of lesbian Native voices, including Beth’s own, broke with a tradition of erasure of Two-Spirit identity, which had been excluded in the emerged and emerging canon of American Indian literature. The “silences and omissions” among literary critics in the field of American Indian literary arts, which Tatonetti insightfully explores in her essay, also contributed to the sense that “lit-crit” gate-keepers (no doubt some of them Native American) were busily deciding whose work was worthy of admission and discussion—and it was not that of “out” American Indian lesbians.

A Gathering of Spirit might not have had immediate critical success in the larger world were it not for Nancy Bereano, who believed in the work and kept it in print through her press, Firebrand Books. This dedication shows that Beth’s selection of writers proved compelling to some readers. It is not simply Beth’s inclusiveness that likely interests readers, but the ways in which she constructs a Native identity through her accessible language of caring and compassion. It may strike some readers as odd that Beth’s Two-Spirit-ness is centered as much on care as on sexuality, yet friendship is an important attribute in lesbian relationships.

Beth and I probably corresponded before we met in person, and we became good friends when she traveled to the West Coast to do readings. I remember sitting with her in the dining room of my old Berkeley house, where I lived with my parents, my older sister, and her little son. It may have been around 1983. Mom sat with us that afternoon, as we talked and laughed over cups of coffee. Beth had been awarded a writing residency on the Marin Headlands, and was a bit apprehensive about going there. I had agreed to drive her out to the residency, since I knew many of the back roads in the area, and I looked forward to showing Beth a part of the California coast that I loved.

___________________________________

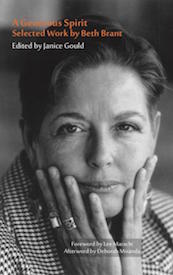

From A Generous Spirit: Selected Work by Beth Brant edited by Janice Gould. Used with the permission of the publisher, Sinister Wisdom. Copyright © by Sinister Wisdom.

Janice Gould

Koyoonk’auwi (Concow) poet Janice Gould has published poetry in over 60 journals and magazines and has won awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Astraea Foundation for Lesbian Writers, the Pikes Peak Arts Council, and from the online publication Native Literatures: Generations. She earned a PhD in English at the University of New Mexico and an MLS from the University of Arizona. Janice is an Associate Professor in Women’s and Ethnic Studies at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, where she developed and directs the concentration in Native American Studies.