How Being a Stalled Novelist Led to an Unexpected Career in Data Science

C.J. Washington on the Frustrating Struggle to Get Published

I wouldn’t be a data scientist if I hadn’t been a stalled novelist. It’s also possible that I wouldn’t be a published author if I hadn’t become a data scientist.

Eight years ago, I was a frustrated writer, exhausted by my unsuccessful efforts to get published. I needed something new, and it felt natural to return to my beginnings: science. As an undergraduate, I’d majored in biology, drawn to its pursuit of knowledge and capacity to solve problems. Interesting things were happening in the field of biomedical engineering, so as I pondered a new career, I set my sights there.

I took mathematics courses at a local university. Instead of writing in the evenings after work, I studied math. On a whim, I enrolled in a computer science course, and I was hooked. I loved the theory and its broad applicability. A computer scientist, I thought, could contribute to any field. It also helped that writing code reminded me of the good parts of writing fiction. They both begin with a goal. There are many ways to accomplish it, and the quality of the end-product lies in part on the virtue of those decisions. As a bonus, the functionality of a completed computer program can be verified. You won’t have one beta reader telling you to change the very thing another beta reader loved.

I returned to school full-time and reveled in the objectivity of my studies. I specialized in artificial intelligence, and unlike the artistic merits of a work of fiction, the mathematical methods employed by AI practitioners were concrete. For a while, I enjoyed what I regarded as the welcome differences between fiction and computer science, namely the existence of right and wrong answers. I didn’t realize how wrong I was or how maddeningly similar the two fields are until I got into more advanced studies.

My primary interest in artificial intelligence is how it can inform us of the workings of the human intellect. I’m fascinated by the human mind and the computational models that probe its mysteries. Those questions are loftier than those I endeavor to answer in my everyday life as a data scientist, but even the pragmatic work I do has more in common with writing than I’d ever imagined.

I view fiction as a subjective enterprise, though I admit that the extent of the subjective versus the objective is arguable. I’ve had long-running, seemingly intractable debates on the topic with several friends. On the surface, the data science I do is objective. (To be clear, I’m referring to the objective as meaning unbiased and falsifiable, not the technical description of objective versus subjective data.) Debates and appearances aside, however, data science and fiction writing share some fundamental similarities.

Novelists and data scientists strive to cloak their quests in a beauty that will draw in their audiences.

For me, fiction at its best is a search for truth. Data science, almost by definition, is also a search for truth. Novelists and data scientists strive to cloak their quests in a beauty that will draw in their audiences. The need to appeal is the struggle that underlies my work as a data scientist and an author. I can’t do either solely for myself. An unimplemented data-driven proposal that could save my company a million dollars is as valuable as a brilliant manuscript that sits in the drawer. I can debate subjectivity versus objectivity ad infinitum, but in the end, my work requires buy-in from others.

As a data scientist, I’m fortunate to work with people who value data in general and machine learning in particular. I advise them on what data to collect, and I analyze the data we own to improve the quality and efficiency of our products. I know data scientists who climb the uphill battle each day of convincing domain experts to trust the algorithms over their instincts. I’m more likely to find myself in the awkward position of being viewed as a magician. We have a lot of data. Can you solve this problem that’s been hampering us for 15 years? No magician wants to reveal their tricks, but I often find myself explaining the limitations of machine learning.

Returning to school provided a welcome hiatus from writing. I didn’t write for five years. I was too busy, and I rarely thought about it. Shortly after I graduated, it came rushing back, the specter of what I thought of as my phantom pregnancy novel, the first manuscript I’d ever completed. I’d tried unsuccessfully to get it published, and it had spent years sitting in a drawer. Now, I took that one element, a woman experiencing a phantom pregnancy, and constructed a new narrative around it.

Some of the characters were the same, but they felt more real now, as if I’d needed to go back to school to discover them fully. The academics I’d gotten to know provided the basis for the professional lives of two of the characters. One, a neuroscientist, is faced with the real-life implications of the limitations of his field. The other, a mathematician, refuses to accept the constraints of her own discipline and seeks to accomplish the unimaginable. Another character, a data scientist, grapples with the conflicting powers of evidence and emotion. And that wasn’t all my time in school supplied. Seeking the intersections of artificial intelligence and the human mind, I’d taken every psychology and neuroscience course I could fit into my schedule. Neuroscience, as it turned out, would play an essential role in my novel.

I found a job that allowed me to work remotely four days a week. I dedicated the time I saved commuting to writing, and I ended up with a novel that I could never have written had I not become a data scientist. Would I be a published author if I hadn’t embarked upon a new career? I’ll never know. But I can say with certainty that I was well-served by the hiatus I took from writing.

__________________________________

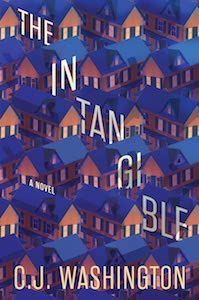

The Intangible is available from Little A. Copyright © 2022 by C.J. Washington.

C.J. Washington

C.J. Washington is a data scientist and writer. Born in Detroit and raised in Atlanta, he earned his master’s degree in computer science from the Georgia Institute of Technology. His primary focus in the computer science field was artificial intelligence (AI), both AI’s application to understanding human intelligence and the application of human intelligence (especially neuroscience) to improving AI. He lives in Atlanta, Georgia, with his wife and daughter. The Intangible is his first novel.