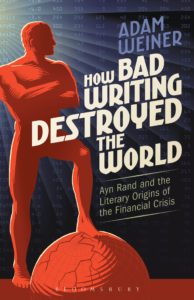

How Bad Writing Destroyed the World

On the Origin of Ayn Rand's Thinking, and a Manchurian Economist Named Greenspan

The loaves of knowledge do not come nicely sliced.

All you get is a stone-strewn field to plough on an exhilarating morning.

–Vladimir Nabokov

The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.

–John Maynard Keynes

Many would be surprised to learn that classic Russian literature offers special insight into the ongoing American economic crisis. In a very real way, this crisis derives from a “defunct economist,” a man who is all but forgotten today, especially outside Russian borders. Nikolai Chernyshevsky (1828-89) was one of the great destructive influences of the past two centuries. His philosophy of “rational egoism,” as he presented it in his history-shaping novel What Is to Be Done? Some Stories about the New People (1863), would later become the foundation of Ayn Rand’s objectivism. At first glance this is surprising since Chernyshevsky is Russia’s great native socialist and Rand our very own arch-capitalist: it would seem that there must be a flaw either in the logic of rational egoism or in the logic of objectivism—or in both. But then logic, which both Chernyshevsky and Rand claimed as central to their philosophy, can create different, even antithetical, results, depending upon its premises. The claim being made in all seriousness is that the rational pursuit of selfish gain on the part of each individual must give rise to the ideal form of society. Odd: the very combination of the words “rational” and “egoism” should summon up grave doubts in those who have felt egoism and possessed sufficient rational sense to calculate its effects. Experience teaches quite the opposite: reason immediately abandons the mind of a person in pursuit of selfish ends. To say that all of this is naïve is to put it charitably—though, ironically, Chernyshevsky’s system, like Rand’s, strictly forbids charity. The deep logic that drives both systems is that of behavioral conditioning. By programming Alan Greenspan with objectivism and, literally, walking him into the highest circles of government, Rand had effectively chucked a ticking time bomb into the boiler room of the US economy. I am choosing my metaphor deliberately: as I will show, infiltration and bomb-throwing were revolutionary methods that shaped the tradition upon which Rand was consciously or unconsciously drawing. While I do not want to equate Lenin’s bloody repression with the economic devastation Greenspan caused as chairman of the Federal Reserve, I will observe that human suffering is a real possibility when “robots” programmed with ideas from destructive books are released upon reality.

How could such folly have become reality—twice? It happened through a combination of bad writers, bad readers, and bad luck. Bad luck, in particular, plays a central role in this story. In this regard Chernyshevsky’s case is astounding. Imprisoned for sedition in 1862 in the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg, he asked for permission to write a novel. For some reason the prison warden granted him permission. The book turned out to be What Is to Be Done?—a thinly disguised training manual for revolutionaries. Next the tsar’s censor allowed the novel to be published on the pages of the widely read journal, The Contemporary, which, under Chernyshevsky’s editorship, had become a hotbed of radicalism. The censor had apparently reasoned that the novel was so dreadfully written that it could only hurt the radical cause: fateful miscalculation. Finally, Nikolai Nekrasov, the great Russian poet and editor of The Contemporary, forgot the only copy of Chernyshevsky’s manuscript in his horse-drawn cab. This should have saved humanity from the consequences of Chernyshevsky’s book, but Nekrasov published a note about the lost manuscript in the paper, and against all odds it was soon returned to him by—of all people—a policeman.

Still, the most surprising part of this story is not attributable to luck. Some devastating algorithm of Chernyshevsky’s novel became very effective at converting people into terrorists. The novel, once published, did not merely arouse spasms of sarcastic laughter (it did that too); it somehow became the cherished book of the next three generations, a catechism for educated young people. The famous Marxist revolutionary Georgy Plekhanov thought the book so important that he published a monograph on it in 1910, arguing that it was an artistic failure but a great source of inspiration for the Russian revolutionary movement. Beyond that, it also established a paradigm for behavior and social interaction immediately in the 1860s and for several generations to come. Irina Paperno paints a colorful picture of this paradigm in her seminal study of Chernyshevsky, where she argues that his “most significant act was the creation of a unified model of behavior for the age of realism, the conception of a new type of personality, with a different orientation to the world and different patterns of behavior, that contemporaries eagerly adopted.” What Is to Be Done? became a “new Gospel” to its adherents, for whom it was “a program of conduct carried out with the kind of piety and zeal inspired in the proselytes of a new religion.” The literary critic Alexander Skabichevsky was in his mid-twenties when Chernyshevsky’s novel appeared, and he later recalled its popularity among the intelligentsia:

We read the novel almost like worshippers, with the kind of piety with which we read religious books, and without the slightest trace of a smile on our lips. The influence of the novel on our society was colossal. It played a great role in Russian life, especially among the leading members of the intelligentsia who were embarking on the road to socialism, bringing it down a bit from the world of drama to the problem of our social evils, sharpening its image as the goal which each of us had to fight for.

Mikhail Katkov, the editor of the journal Russkii vestnik (The Russian Messenger), wrote that young people in the 1860s worshipped Chernyshevsky’s novel “like Moslems honor the Koran.” This new religion, while built upon a foundation of determinism, indulged its followers with the idea of endless personal freedom by depicting again and again an almost miraculous process of transformation by which socially inept people became like aristocrats, prostitutes became honest workers, and hack writers became literary giants. In imitation of Chernyshevsky’s fictional heroes, young men would enter into fictitious marriages with young women in order to liberate them from their oppressive families. The nominal husband and wife would obey Chernyshevsky’s rules of communal living, with private rooms for everybody and sexual relations by mutual consent. In imitation of the sewing cooperative in Chernyshevsky’s novel, communes began sprouting all over the place. The imitators of Chernyshevsky’s heroes, especially of his superman, Rakhmetov, would eventually include extremists like Vera Zasulich, Nikolai Ishutin, Dmitry Karakozov, Sergei Nechaev, and Alexander and Vladimir Ulyanov (Lenin).

Fyodor Dostoevsky was a mawkish and second-rate writer in 1863, but grasping the apocalyptic potential of What Is to Be Done?, he was compelled to reinvent himself as a brilliantly innovative novelist in order to fight Chernyshevsky and the westernizing trend he represented. Dostoevsky’s first great work of literature, Notes from Underground (1864), was a direct response to Chernyshevsky’s novel. His four classic novels, Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1868), The Devils (1872), and The Brothers Karamazov (1880), build upon the stylistic discoveries made, so to speak, in the laboratory of the underground. For much of the remainder of his life, Dostoevsky continued to ridicule Chernyshevsky’s ideals, attempting to replace them with a mystical religious alternative he would come to call the “Russian Idea.” The decade that followed the publication of What Is to Be Done? witnessed a strange race between life and literature, as Dostoevsky kept trying to stomp out the revolutionary fire, while the living imitators of Rakhmetov kept lighting new ones. Dostoevsky died, and the fire spread out of control. Lenin read What Is to Be Done? and was reborn an austere, uncompromising, real-life Rakhmetov. He would go on to lead the Russian Revolution and authorize the Red Terror, bequeathing an apparatus and methodology of repression to Stalin.

Having escaped the Red Terror, Nabokov spent twenty years in Europe, writing under the pen name of V. Sirin and becoming the greatest novelist of the Russian diaspora. The last novel Nabokov wrote in Russian is his farewell to Russian literature, The Gift (1937). At the heart of The Gift is an eccentric biography of Chernyshevsky that is meant to contain and neutralize the harmful influence of What Is to Be Done? Nabokov’s novel is an exorcism by satire: Chernyshevsky was a materialist but he did not know nature; he raised the blind worship of material things to a spiritual level. Nor does Nabokov spare Dostoevsky, whom he portrays in a ludicrous light in his encounter with Chernyshevsky. From Nabokov’s point of view Chernyshevsky and Dostoevsky were both hacks because they favored ideology over artistic considerations. Chernyshevsky’s communist utopia and Dostoevsky’s Christian one are both rubbish. According to Nabokov’s aesthetic, a good writer strives first for perfect form, which in turn chooses its own content; and art must be created according to its own standards rather than bent to the artist’s ideology; otherwise it is mere propaganda. Nabokov’s ingenious novel was, of course, bypassed by history.

Ayn Rand had grown up as Alisa Rosenbaum in Dostoevsky and Nabokov’s beloved St. Petersburg. By virtue of some whimsical plotting on the part of fate, she had played as a small child with Nabokov’s sisters at the Nabokov mansion. She grew up at a time when Chernyshevsky’s influence was ubiquitous and unassailable, when it was one of the Russian intelligentsia’s cherished pastimes to imitate Chernyshevsky’s literary characters and attempt to incarnate his ideas in their own life and flesh. While justifiably terrified of the Revolution and loathing its ideals, the brooding young Rosenbaum had taken on board the rational egoism and superheroism of one of its chief plotters. It was with this contraband that Rosenbaum fled to the United States in 1926, rebranding herself Ayn Rand. Even as Nabokov was trying to drive a stake through Chernyshevsky’s heart, Rand was raising Chernyshevsky from the dead in the graveyard of bad ideas. She would resurrect his rational egoism, his zealous belief that, in Rand’s words, “form follows purpose” in art, and, most importantly, his image of the fictional hero as uncompromising revolutionary “rigorist,” or, as Rand put it, “the extremist.”

It is strange to think that Nabokov was at work on The Gift during the very years when Ayn Rand was writing The Fountainhead (1943), her first big literary success. Both would soon be enormously popular American novelists. Nabokov’s examination of the legacy of Chernyshevsky gave him the idea to ensnare him in a book, transforming him from an uncontrollable historical force to a manageable literary character. Rand was doing just the opposite, resurrecting Chernyshevsky in order to spring him anew upon the world. Nabokov immigrated to the United States in 1940, and never seems to have intersected with Rand on American soil. William F. Buckley Jr. started his campaign against rational egoism and its aftereffects where his friend Nabokov had left off. Buckley’s relationship with Ayn Rand over the decades, though not entirely devoid of friendly feelings, was strained and awkward. As two leaders of the conservative movement who mostly agreed on economic matters, they might have been allies, but a chill entered their relations from the very start, when, according to Buckley, Rand scolded him that he was “too intelligent to believe in God.” When Rand broke with Buckley, she alienated herself from the conservative movement, blundering into increasingly strange ideological terrain, where she became subject to the delusions of cultish isolation and foolishly magnified her importance. In the early 1950s she was reading aloud from the manuscript of Atlas Shrugged to her acolytes in “The Collective,” as Alan Greenspan and the others who made up Rand’s coterie called themselves, and by now she was too far gone in self-aggrandizement to be capable of responding to criticism. It was perhaps out of a higher principle than mere revenge lust that Buckley asked Whittaker Chambers to review Atlas Shrugged for The National Review. Buckley later commented, “I believe she died under the impression that I had done it to punish her for her faithlessness,” but he maintained that it was not a hit piece he had asked Chambers to write.

In any case, Chambers responded by writing “Big Sister Is Watching You.” He called Atlas Shrugged “a remarkably silly book,” a “ferro-concrete fairy tale” in which all characters are either caricatures of good or caricatures of evil. The novel, wrote Chambers, describes a war between the “Children of Dark” and the “Children of Light.” The Children of Dark are all “looters,” that is “base, envious, twisted, malignant minds, motivated wholly by greed for power, combined with the lust of the weak to tear down the strong, out of a deep-seated hatred of life and secret longing for destruction and death.” The Children of Light are superhuman characters who triumph over the collectivist looters by declaring a capital strike. Chambers mistrusts Rand’s rearrangement of the world, which she hands over to the inventors, engineers, and industrialists, and Chambers’ best insight is that it is precisely Rand’s tedious, grating “dictatorial tone” that unmasks her as “big sister.” And truly, the essential core of both Chernyshevsky’s and Rand’s thought is not socialism or capitalism but the tyrannical will to control humanity and shape its destiny.

Out of a lifetime of reading, I can recall no other book in which a tone of overriding arrogance was so implacably sustained. Its shrillness is without reprieve. Its dogmatism is without appeal. In addition, the mind which finds this tone natural to it shares other characteristics of its type. 1) It consistently mistakes raw force for strength, and the rawer the force, the more reverent the posture of the mind before it. 2) It supposes itself to be the bringer of a final revelation. Therefore, resistance to the Message cannot be tolerated because disagreement can never be merely honest, prudent, or just humanly fallible. Dissent from revelation so final (because, the author would say, so reasonable) can only be willfully wicked. There are ways of dealing with such wickedness, and, in fact, right reason itself enjoins them. From almost any page of Atlas Shrugged, a voice can be heard, from painful necessity, commanding: “To a gas chamber—go!”

Rand never forgave Buckley this review, which she pretended not to have read; her followers, he claimed, were forbidden from so much as mentioning it. Buckley, in a television interview, described Atlas Shrugged as “a thousand pages of ideological fabulism” and chuckled that he had had to “flog” himself to read it. He periodically called Rand up on the phone in an attempt to make peace. She would pick up the phone, listen for a second, utter, “You are drunk!” and hang up in disgust. In an evilly gloating obituary Buckley announced in 1982 that Ayn Rand’s “stillborn” philosophy had died with its author. He was wrong: in 1982 Ayn Rand’s thought was in fact only gathering steam. Alan Greenspan would soon be transforming Rand’s “stillborn” ideas into “zombie” policy.

If Chernyshevsky awakened Lenin, then Ayn Rand did the same for Alan Greenspan. “I was intellectually limited until I met her,” wrote Greenspan: “Rand persuaded me to look at human beings, their values, how they work, what they do and why they do it, and how they think and why they think. This broadened my horizons far beyond the models of economics I’d learned.” I want to pause to take in this picture of Alan Greenspan studying “human beings” in order to learn their ways. Rand first cowed Greenspan, then groomed him, converting him from a self-proclaimed “logical positivist” to one of her most loyal objectivists. Upon publication of Chambers’ review, it was Greenspan who took it upon himself to write a letter of sycophantic protest to Buckley, complaining, “This man is beneath contempt and I would not honor his ‘review’ of Ayn Rand’s magnificent masterpiece by even commenting on it.” This was just the sort of loyalty that Rand demanded and rewarded. Having reprogrammed Greenspan, she accompanied him (and his biological mother) to the White House, where he was sworn in as the president’s chief economist. Disappointed that her novels, particularly Atlas Shrugged, had failed to transform reality into an objectivist paradise, Rand had created in Alan Greenspan a final devastating hero, heir to Rakhmetov, heir to John Galt, and freed him from her pages that he might operate unfettered in the medium of history. Greenspan was the flesh of her mind, her idea incarnate, and she must have wanted to live through him, as he began to wield objectivism, first in the White House, after her death in the Federal Reserve, where he would offer up the US economy in a spectacular hecatomb.

From HOW BAD WRITING DESTROYED THE WORLD. Used with permission of Bloomsbury. Copyright 2016 by Adam Weiner,

Adam Weiner

Adam Weiner is Associate Professor of Russian and Comparative Literature at Wellesley College, USA. His first book was By Authors Possessed: The Demonic Novel in Russia (2000). His book How Bad Writing Destroyed the World is out now from Bloomsbury.