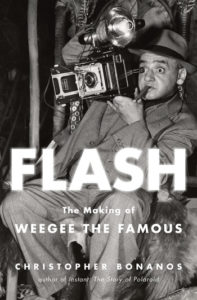

How Arthur Fellig Became the Legendary Street Photographer Weegee

Capturing the Face of Mid-Century New York City

“I keep to myself, belong to no group,” Weegee once wrote, and it was true that he remained an odd-shaped peg that fit in few holes. Despite his eagerness to talk about taking pictures, he never joined the New York Press Photographers Association, as nearly all his colleagues did. Nonetheless, in the early 1940s, he did sidle his way into the fringes of one club, perhaps because it was so thoroughly devoted to the nuts and bolts and art and craft of photography.

The Workers Film and Photo League had gotten its start in New York around 1930, an outpost of a leftist photographers’ and filmmakers’ association in Berlin. In 1936, the American group split in two, and the half devoted to nonmoving pictures renamed itself the Photo League and rented a floor at 31 East 21st Street. There, one flight up from an upholstery shop, it became one of the very few places in the United States focusing on documentary photography—distinct from press photography because it was concerned with recording everyday life more than particular events—and especially documentary photography as art.

The Photo League’s main force was a big, intense fellow named Sid Grossman. He edited its journal, served as director, and coached and taught (and often harangued) younger photographers to make their pictures more honest and substantial. Serious photography was a small town at the time, and he got a lot of help from people who are now known as great talents of their generation: Berenice Abbott, Ralph Steiner, Walter Rosenblum, Aaron Siskind, W. Eugene Smith. The place also had its share of dilettantes and hangers-on, people who, as up-and-comer Arthur Leipzig later recalled, “just liked being there. Sometimes there’d be a speaker who’d come in and talk, and we enjoyed that. Other times there was a lot of garbage.”

When Weegee started dropping by the gallery on 21st Street, at first he would just sit in the back and listen to the other photographers talk. Given the extroverted stances some of them exhibited, there was plenty to hear. The group’s worldview was colored by the members’ politics, which were generally socialist leaning toward Communist. Many of the League’s members, such as Leipzig and Rosenblum, were the children of working-class or middle-class Jews from Brooklyn and the Lower East Side. Nearly all strived for their work to inspire social reforms, but instead of going to the Dust Bowl to send pictures back to Life, most of the men and women of the Photo League did it at home, among the first-generation Americans they knew.

Grossman made notable pictures of the labor movement. Others photographed streetscapes, tenement life, poor and working-class kids, and scenes from Jewish and Italian and African American ghettos. The League’s front room on 21st Street was a gallery where shows of this work could be hung and lectures delivered, with darkrooms built down the side, where the photographers could process their work. It was a contentious but congenial clubhouse for energetic people whose hands smelled like hypo.

Starting in mid-1941, Weegee became a dues-paying member of the Photo League, but he never quite became an insider. “He never was very close to them,” Wilcox later explained. “He was a loner—he knew them, they knew him, but he was different. They knew that he kept to himself.” Unlike most of the group, he was not (explicitly) devoted to social-justice commentary; he was shooting to sell as well as to inform. The Photo League’s members tended to intellectualize their work. And even though his photographs consistently reflected many of the League’s activist ideals, he was (perhaps owing to his lack of formal education, perhaps to his streetwise cynicism) suspicious, even dismissive, of those who claimed they were doing something for the greater good.

“Messages?” he once told his friend Peter Martin. “I have no time for messages in my pictures. That’s for Western Union and the Salvation Army. I take a picture of a dozen sleeping slum kids curled up on a fire escape on a hot summer night. Maybe I like the crazy situation, or the way they look like a litter of new puppies crammed together like that, or maybe it just fits with a series of sleeping people I’m doing. But 12 out of 13 people looked at the picture and told me I’d really got a message in that one, and that it had social overtones.”

The Photo League became one of the very few places in the United States focusing on documentary photography.

The social aspect of the Photo League led to networking as well as flirtation, of course. In the spring of 1940, the talk of the New York press world was a new newspaper that was meant to overturn just about every conventional approach to the business. Ralph McAllister Ingersoll, the strong-willed and patrician editor who had helped launch Henry Luce’s Fortune and Life, had been thinking for a couple of decades about everything that was wrong with the press and how he might start anew.

He had, the previous year, taken an open-ended leave from his role as general manager of Time Inc. to get his idea going, and his connections had helped him raise a great deal of start-up capital. One of the biggest investors was Marshall Field III, the department store heir, and the rest of the list included a lot of household names: Wrigley, Whitney, Schuster, Gimbel. There was so much interest that Ingersoll said he ended up turning down a million dollars’ worth of investments, a move he would regret later.

Ingersoll saw an underserved readership: New Yorkers who wanted a leftist newspaper that was smart about international and domestic affairs (like the Times) but that also embraced powerful photography (like the tabloids and Life and its competitor Look) and sharp, voicey writing, especially opinion writing (as in the Herald Tribune but from the opposite side of the aisle). The general idea was to do a tabloid for the highest common denominator rather than the lowest, and Ingersoll thought he could peel off “the most intelligent million of the three million who now read the Daily News and the Daily Mirror.” His prospectus, widely quoted and reprinted multiple times in the paper itself, put forth the memorable line “We are against people who push other people around, just for the fun of pushing, whether they flourish in this country or abroad.”

PM was to be a liberal but not radical paper, pro-Roosevelt, pro-union, pro-New Deal, and anti-anti-Semitic. From the beginning, it was loudly critical of fascism and especially the Nazis. It was supposed to be not just factually solid and journalistically sound but emotionally engaging. It was to be readable, more like a magazine than a newspaper, eschewing the clutter and chaos of most tabloids’ pages. It would have no ads, and to make up the difference, it would cost a nickel at the newsstand instead of the other papers’ two or three cents. Most of all, Ingersoll said, “Over half PM’s space will be filled with pictures—because PM will use pictures not simply to illustrate stories, but to tell them. Thus, the tabloids notwithstanding, PM is actually the first picture paper under the sun.”

PM did look like a genuinely promising paper, and Ingersoll was apparently deluged with employment applications from idealistic young reporters. Weegee, by contrast, didn’t chase a job; instead, he said, he waited for them to come to him. The photo editor hired to help launch PM was William McCleery, who had worked at the AP and at Life, and thus was sure to have known Weegee’s work and growing reputation. And what McCleery and Ingersoll had to offer him was significant: instead of suppressing its contributors’ styles and credits in favor of an institutional voice, PM was going to go the opposite way and try to showcase the individual personality of everyone who worked there. Not only would photos carry their makers’ names; there would be substantial captions that would sometimes make an attempt to show how the news had been gathered and made. If you did great stuff for PM, everyone would know youhad done it.

Weegee made a deal with PM that was mutually beneficial: he would bring them his work first, on no fixed schedule, and they’d put him on a retainer of $75 dollars per week. That was upper-middle-class money for a single man in 1940, nearly as much as he’d been making as a freelance. For the first time in his freelance life, Weegee would have a guaranteed steady income, and a good one at that. He would also be able to keep selling his work to Acme and the other syndication services and to any magazines that came calling. PM would merely get first crack at his take.

At PM, Weegee was, for the first time, top dog, one of two established talents on the team, the other being the already legendary Margaret Bourke-White. Brilliant and glamorous, and paid triple what Weegee was getting, she still didn’t last in the job. She was far too obsessive and perfectionistic an artist to deal with newspaper work. She’d be sent out to document some corner of Hell’s Kitchen or Brownsville, and would come back with hundreds of not-yet-processed negatives an hour before her press deadline. She washed out and went back to magazines within the year.

Once she left, Weegee became the ace of the photo department. It may have irritated his colleagues, but Weegee’s rough-edged garrulousness got him places. On one of his first days at the PM offices, possibly even before he signed on, he was cracking wise to a colleague about something he’d seen, and Ingersoll overheard him.

The editor recognized Weegee’s voice for what it was—funny, distinctive, New Yorky, exactly what he wanted in his paper. Indeed: the man had, even before PM was officially open for business, found his audience and his conduit to it. His photo-gearhead interests, his unique voice, his shticky sense of humor, his view of proletarian New York, his photographic ambitions, even (in the form of that pastrami sandwich) his Lower East Side Jewishness—all of it fit into PM’s editorial ethos.

The paper itself was a half success, its strengths and weaknesses alike bound up in Ingersoll’s arrogance toward his competitors. Readers had expected a transformative media experience from PM, and what they got instead was an inconsistent and often late-to-the-story but pretty good newspaper whose reach, editorial and otherwise, exceeded its grasp. (In just one of many gaffes, the circulation department accidentally lost the entire list of paid-up charter subscribers, and those readers never got their papers.) Yet although the writing and editing were uneven, Weegee, Haberman, Fisher, and their colleagues hit their targets a very high percentage of the time. Almost every edition contained at least a couple of great photographs.

The closest Weegee ever came to explicit activism was probably a set of photographs he made in July 1940. He (or perhaps an observant policeman or editor) had begun to notice a striking number of car crashes on the Henry Hudson Parkway, the elevated highway along the western edge of Manhattan, right by the 72nd Street on-ramp. Over the preceding year, he had collected a horrifying set of photographs of twisted cars, over and over, every one at the same spot.

In fifteen months, ten cars had crashed, four people had been killed, and nineteen had been hurt. This was classic outrage reporting, a small-bore version of what the radical investigative journalist I. F. Stone did, but instead of gleaning facts and figures from public records Weegee did it with a camera and patience. (He wasn’t always so patient. Weegee once delivered a similar story to the Post as well, and for that one, he had come up with 11 wreck photos on the streets, then padded out the total to a baker’s dozen by visiting an auto junkyard.)

This time, at least, it worked. The city undertook a traffic study, and a few months later guardrails went up and the curb was rebuilt. PM took credit for it, reproducing its page from the previous summer with a new photo of the reconstructed intersection. It was a small victory, but Weegee was proud of the result. “This work,” he later wrote proudly, “I consider my memorial.”

________________________________________

From Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous. Used with the permission of the publisher, Picador. Copyright © 2019 by Christopher Bonanos.

Christopher Bonanos

Christopher Bonanos is city editor at New York magazine, where he covers arts and culture and urban affairs. He is the author of Instant: The Story of Polaroid. He lives in New York City with his wife and their son.