How Anthony Comstock, Enemy to Women of the Gilded Age, Attempted to Ban Contraception

Hell Hath No Fury Like a Man with a Vaginal Douche Named After Him

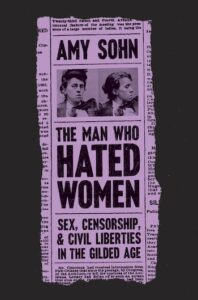

Speech is a form of power. My new book, The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, & Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age, chronicles eight women “sex radicals” who went up against the restrictive 19th-century federal Comstock law—named after the obscenity fighter Anthony Comstock—which criminalized the mailing and selling of contraceptives with harsh sentences and steep fines.

Dr. Sara Blakeslee Chase was a little known sex radical who was trained in homeopathic medicine and touted the benefits of voluntary motherhood, or small families. After her lectures she often sold contraceptive syringes. Vaginal syringes were commonly used by Victorian-era women, who filled them with substances ranging from acids to water, and douched with them after sex to reduce the chance of pregnancy. They could also be used to try to end pregnancies, with some doctors even recommending them for this purpose. They were still available even after the Comstock law’s passage because they were cheap, easy to find, and not explicitly contraception—druggists and doctors recommended them for hygiene and health.

In the spring of 1878, Anthony Comstock received word that a young woman who had attended one of Sara’s lectures in a church in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, had used a vaginal syringe that she bought from Sara, and then ulcerated her uterus. A doctor took care of her and she recovered. Anthony’s accounts of what happened are convoluted. The most important man in the lives of 19th-century women, he did not understand the difference between contraception and abortion and frequently conflated them in his arrest logbook accounts.

Together his accounts indicate that the young woman used a syringe as a contraceptive, got pregnant anyway, and then went to an abortionist—not Sara—who botched the procedure. Sara maintained for decades that she did not perform abortions and was opposed to them, even calling them “foeticide.”

Infuriated by the story of the Williamsburg girl, Anthony went to Sara’s home. Calling himself “Mr. Farnsworth,” he bought a syringe for five dollars. He returned on another day, revealed himself as Anthony Comstock, and brought in a cop and a New York Tribune reporter who were waiting across the street. He locked Sara’s boarders and patients in their rooms, ransacked the house, and found six syringes.

She was arrested and held on $1,500 bail and charged with selling articles for a criminal purpose under the New York state, or “little” Comstock law. The grand jury decided to dismiss the case because the district attorney felt that it was not “for the public good.”

After her case was dismissed she sued Anthony for false arrest, seeking $10,000—or around $275,000 in today’s dollars. She charged that he had injured her reputation and profession as a physician, causing the loss of clients and inflicting financial damage.

Anthony’s arrest was only the beginning of Sara’s campaign against him. In the pages of her health and progressive journal, The Physiologist & Family Physician, she wrote anti-Comstock screeds. She called his mind “vile” and his judgment “perverted,” and said he did not grasp “the difference between obscenity and science.”

The most important man in the lives of 19th-century women, he did not understand the difference between contraception and abortion and frequently conflated them in his arrest logbook accounts.

In the June/July 1878 issue, she ran a notice for a new item to be sold to Physiologist readers. It was called the “‘Comstock’ Syringe.” The ad stated that it was the same one Sara had sold Comstock himself. It was “especially adapted to purposes of cleanliness, and the cure and prevention of disease.” Sara concluded, “We trust that the sudden popularity brought to this valuable syringe by the benevolent agency of the enterprising Mr. Comstock, will prove to suffering womanhood the most beneficent act of his illustrious life.”

A later “Comstock syringe” ad mentioned her lawsuit as a selling point, to let purchasers know that to buy a douche named after Comstock was a form of political action. It said the syringe was used by married women for the “judicious and healthy regulation of the female functions” (ode for preventing pregnancy) and was “a Blessing to Womankind.”

Comstock was so furious to see a vaginal douche being advertised under his name that he got a different grand jury to indict her, without informing them that her case had previously been dismissed. The assistant district attorney secured a nolle prosequi, declining to prosecute, and admonished him for withholding information and not going through the proper channels.

Furious that he could not get Sara locked up, Anthony vowed to ban the syringe, raid the Physiologist offices, and put Sara and her managing editor, Samuel Preston, behind bars. The duo secured bail and a lawyer. After Samuel wrote an article calling Anthony “a loathsome moral leper” and a fraud, the journal was banned by the post office. The duo and their supporters succeeded in getting mailing privileges restored. In celebration, Sara and Samuel filled their entire back page with an ad for the Comstock syringe, with testimonials from doctors, editors, and customers. “Anthony Comstock has at least been of some service to humanity in calling public attention to such a blessing as your Syringe,” read one.

Though Sara and Samuel managed to put out only a few more issues of the Physiologist before they had to fold it due to lack of money, the Comstock syringe lived on. Two prominent Massachusetts free lovers, the married couple Angela and Ezra Heywood, were so taken by Sara’s story and writing that they advertised a Comstock syringe in their free love journal, The Word. The first ad said, “If Comstock’s mother had had a syringe and known how to use it, what a world of woe it would have saved us!”

Though they probably didn’t know it, Comstock’s mother, Polly Comstock, had died at age 37 after hemorrhaging following the birth of her sixth child (a different account claimed that it was her tenth). The Heywood’s ad was cheeky, implying that the world would have been better if Anthony had never been born. But if Polly Comstock really had had a syringe and chosen to use it, it might have saved her from death. Rather than become a champion of women’s reproductive rights when he came home from school at the age of ten to find his mother dead, he became emboldened in his quest to make all women more like his mother, a pure, saintly, Christian wife and mother whose mission was to be fruitful and multiply—the Victorian ideal.

Another Comstock syringe ad in The Word said, “Comstock tried to imprison Sarah [sic] Chase for selling a syringe; she had him arrested and held for trial, while the syringe goes ‘marching on’ to hunt down and slay Comstock himself! Woman’s natural right to prevent conception is unquestionable; to enable her to protect herself against invasive male use of her person the celebrated Comstock Syringe, designed to prevent disease, promote personal purity and health, is coming into general use.”

But soon the Heywoods realized that they might be crediting Anthony with too much by naming a vaginal douche after him. In an issue several months after their first ad ran, they proclaimed that the product would thereafter be named “The Vaginal Syringe,” so that “its intelligent, humane and worthy mission should no longer be libelled by forced association with the pious scamp who thinks Congress gives him legal right of way to and control over every American Woman’s Womb.”

Comstock was so furious to see a vaginal douche being advertised under his name that he got a different grand jury to indict her.

In October 1882 Anthony arrested Ezra, who had previously served six months in Dedham Jail for obscenity, on four counts of sending obscene matter. One count was for publishing an edition of The Word that contained two Walt Whitman poems, “A Woman Waits for Me” and “To a Common Prostitute.” Two were for issues that contained Comstock syringe ads.

Angela Heywood, who had a looser, more discursive, and provocative writing style than her husband, argued in The Word that the charges were unjust. To her, syringes were symbolic. In an 1883 essay she wrote, “Not books merely but a Syringe is in the fight; the will of man to impose vs. the Right of Woman to prevent conception is the issue… Does not Nature give to woman and install her in the right of way to & from her own womb? Shall Heism continue to be imperatively absolute in coition? Should not Sheism have her way also? Shall we submit to the loathsome impertinence which makes Anthony Comstock inspector and supervisor of American women’s wombs? This womb-syringe question is to the North what the Negro question was to the South.” She and Ezra had met in New England abolitionist circles and she frequently described women as enslaved by marriage, sexism, and economic inequality.

She proposed a satirical alternative to the Comstock law: a man would “flow semen” only when a woman said he could. She suggested other rules. A man had to keep his penis tied up with what she called “‘continent’ twine,” which he would have to keep nearby to assure his virtue. If he were found without the twine, he would be “liable, on conviction by twelve women, to ten years imprisonment and $5000 fine.” She then proposed “that a feminine Comstock shall go about to examine men’s penises and drag them to jail” if they dared break the semen-twine law.

The trial began in April 1883, in Worcester, Massachusetts. Ultimately, the judge threw out all charges except those related to the syringe. Ezra, representing himself, told the jury that women had a right to control conception. He said, “The man who would legislate to choke a woman’s vagina with semen, who would force a woman to retain his seed, bear children when her own reason and conscience oppose it, would way lay her, seize her by the throat and rape her person. I do not prescribe vaginal syringes; that is woman’s affair not mine; but her right to limit the number of children she will bear is unquestionable as her right to walk, eat, breathe or be still.” He called the charges “an effort to supervise maternal function by act of Congress.”

The judge told the jurymen that the government had to demonstrate that the syringe advertised in The Word was manufactured for the purpose of preventing conception. The men wanted to acquit from the beginning but also wanted lunch on the government’s tab. After eating their meal, they waited until three o’clock to give the verdict: not guilty of obscenity on the remaining charges. Ezra and Angela’s supporters burst into applause. In a speech before the New England Society for the Suppression of Vice, Anthony said that the court had “turned into a free-love meeting.”

Ezra was acquitted, but a month later, he was arrested under Massachusetts law for mailing a reprint of several Word articles that included the “Syringe is in the fight” essay. Though Angela’s words had led to his indictment, Ezra was charged for mailing the reprint. Angela was pregnant with their fourth child, and Ezra thought it would send a strong sympathetic message if she were put on the stand. She, in turn, wanted to be charged for her writing when Ezra had repeatedly been charged for mailing the offending issues. She felt that he was being prosecuted because women were too sympathetic on the stand. Proudly, she wrote in The Word that the trial was one in which a woman had “persistently kept the words Penis and Womb traveling in the U.S. Mails.”

Rather than become a champion of women’s reproductive rights, he became emboldened in his quest to make all women more like his mother.

The trial was postponed four times due to her pregnancy. The judge ruled that the prosecutors had to charge and prove a willful intent to corrupt the morals of youth, which he did not believe they did, and dismissed the charges.

In The Word, Angela began to use even franker language, writing in 1887 that “Cock is a fowl but not a foul word; upright, integral, insisting truth is the soul of it, sex-wise.” In 1889 she wrote, “Such graceful terms as hearing, seeing, smelling, tasting, fucking, throbbing, kissing, and kin words, are telephone expressions, lighthouses of intercourse centrally immutable to the situation.”

But none of these strongly-worded pieces led to indictments. Instead, it was Angela’s “Syringe is in the fight” essay that landed Ezra in court for the third and final time. In the spring of 1890, more than 12 years after his first arrest, Ezra was indicted by a federal jury in Boston on three counts of obscenity published in The Word. One was for an April 1889 reprint of Angela’s syringe essay. Throughout the trial, Angela, who sat with one of the children on her lap, kept her gaze fixed on Ezra’s face. The jury found Ezra guilty on two charges, one involving the essay. He was sentenced to two years’ hard labor in Charlestown State Prison.

He was released in May 1892 and about a year later, died of an illness most likely contracted in prison. Angela was unable to keep printing The Word, and its last issue appeared the following April, after a 21-year run. She died in Brookline, Massachusetts, at the age of 94, having outlived her beloved husband by more than four decades.

As for Sara Chase, in June 1893, she was convicted of manslaughter in New York, in relation to a young woman patient named Margaret Manzoni. The woman had gotten a botched abortion from an abortionist and was transferred to Sara when it appeared she might die. Sara tried to save her but Manzoni died, and Sara was sentenced to nine years and eight months in the State Prison for Women in Auburn, New York. She was released in the fall of 1899, with time off for good behavior.

She was 62.

She kept giving sex lectures, and supported herself with needlework. After relocating to Pennsylvania, she mailed a syringe in response to a decoy letter sent by an associate of a deputy marshal. Comstock helped him track her to Elmora, New Jersey. In June 1900 she was arrested, and held in Newark on $2,500 bail, charged with being a fugitive from justice and sending improper medical advertisements. The case never went to trial.

Sara moved to Kansas City, Missouri, along with her daughter and son-in-law. She abandoned contraceptive sales, and died in Kansas City at age 73. While in prison she wrote a letter that was published in a prominent free love journal: “The need of reform is to be seen on every hand, yet all do not see it, and those who do are unable to resist the innate hatred of injustice and wrong that impels them to try to remedy the evils that lie in their way. They do not stop to count the cost. They only say, ‘This work must be done and I must help.’”

__________________

From The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, and Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age, copyright © 2021 by Amy Sohn. Used by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Amy Sohn

Amy Sohn is the author of several novels, including Prospect Park West and Motherland. A former columnist at New York magazine, she has also written for Harper’s Bazaar, Elle, The Nation, and The New York Times. She has been a writing fellow at Headlands Center for the Arts, Art Omi, and the Studios at MASS MoCA. A native New Yorker, she lives in Brooklyn with her daughter.