How Anne Boleyn Captured Our Collective Imagination

John Guy and Julia Fox on the Death and Afterlife of Tudor England's Most Famous Queen

Shortly after dawn on Friday 19 May 1536, Sir William Kingston, Constable of the Tower of London, left his quarters near the eastern perimeter of the fortress and set out around the west side of the White Tower. Passing through the Coldharbour Gate, the great tower and gateway built by Henry III in around 1240 to guard the entrance to the royal apartments, he gained admission to the innermost ward. Arriving at the queen’s lodgings, he mounted the stairs at the south end of the building, and then passed through the recently rebuilt Presence Chamber. After he reached the door of the more intimate privy chamber, he gently knocked.

A lady-in-waiting opened it, and beyond was a slim, thirty-five- or thirty-six-year-old woman of average height with dark, flashing eyes and a long, slender neck—Queen Anne Boleyn, second wife of King Henry VIII. This was not the first time that Kingston had visited her at this hour. She had sent for him early in the morning on Thursday, after keeping an anxious vigil since 2 a.m., kneeling in prayer with John Skip, her trusted almoner. Under sentence of death, she had summoned Kingston while she received the holy sacrament of the Mass and protested her innocence of the heinous crimes of which she was accused: incest, quadruple adultery and plotting to kill her husband. Swearing twice on the sacrament that she spoke God’s truth, she declared that she was “a good woman” and had never been unfaithful. Her belief was that she would die shortly after 8 a.m., the customary hour for such executions. Steeling herself to walk to the scaffold, she had spent many long hours of waiting that night, reconciling herself to what was to come.

If Anne dreamed that her former lover would save her, she barely knew him.

She so readied herself, because one of the four former ladies- in-waiting whom her husband had redesignated as her custodians and whom she detested—possibly her aunt, Lady Elizabeth Boleyn—had informed her that she would die that day. It was a cruel misunderstanding. The date and time of execution had not yet been fixed. When nothing happened, she became sorely distressed. Sending for the Constable again, she said: “Master Kingston, I hear say I shall not die afore noon, and I am very sorry therefore, for I thought then to be dead and past my pain.” Unbeknown to her, Henry would not approve her death-warrant until later that same Thursday. When the writ was finally sealed, it instructed Kingston that “immediately on receipt of these presents, you bring the said Anne upon the Green within our Tower of London, and cut off the head of the said Anne, and in this omit nothing.”

There were other reasons for a delay. During daylight hours, the gates of the Tower were left open to permit visitors to access the outer ward. Not wishing to arouse suspicions, but keen to restrict independent reports of the manner of Anne’s death from traveling abroad, Thomas Cromwell, the king’s principal secretary and chief enforcer, had ordered Kingston to expel some thirty foreigners from the Tower precincts before the execution could begin. Cromwell appointed his staunch ally, the merchant-banker Richard Gresham, soon to be Lord Mayor of London although he was one of the most hated men in the city, to take charge of security and make sure only those whom the king wished to see his wife die should be allowed to enter “because of [the] wondering of the people.” Equally, Henry, who was planning everything from afar in the minutest detail, intended everyone who mattered to be there. Given the initial uncertainty as to the date and time, Kingston worried that “if we have not an hour certain [as it may] be known in London, I think here will be but few and I think a reasonable number were best.” On that score, he need not have feared.

A man not without some human sympathy, Kingston tried to divert Anne’s attention from the muddle over the timetable. “It should be no pain,” he answered, “it is so subtle.”

“I heard say,” she replied, “the executioner was very good, and I have a little neck.” At this, she “put her hand about it, laughing heartily.” All through her life, she had never lacked courage and it did not fail her now. “I have seen many men and also women executed,” Kingston informed Cromwell, “and all they [i.e. all of them] have been in great sorrow, and to my knowledge this lady hath much joy and pleasure in death.” With her marriage and her reputation destroyed, Anne had put her faith in a redeeming Christ.

By Friday morning, everything was ready. Anne had spent a second night with Skip, kneeling in prayer, too exhausted to sleep. As dawn broke, Kingston reappeared to tell her she would die that day and to give her a purse containing £20 which she was to distribute, according to tradition, as alms before her death. Sometime after 8 a.m., he returned: the moment was approaching. Anne dressed herself with the greatest care for her final appearance on a public stage. As a teenager at the court of Queen Claude of France, she had learnt about the power and symbolism of beautiful clothes. The occasion demanded sobriety, not flamboyance, and so today she chose a gown of grey damask lined with fur, over which she wore an ermine mantle. Her choice is telling, because dark or neutral shades of silk or satin rarely found a place in her wardrobe. She had never worn grey or black: colors too closely associated with her predecessor as queen, Katherine of Aragon. She then tied up her still lustrous dark brown hair, over which she wore an English gable headdress, another unusual choice for her as she tended to prefer the more fashionable and flattering French hoods. We should not overlook the significance of her hood. Anne had been a Francophile from a young age: her tastes and values were radically different to those of previous royal consorts—but this was an occasion to protest her loyal Englishness.

Attended by Lady Boleyn and the three other ladies, she left her privy chamber for the last time and went downstairs into the open air. Crossing the inner courtyard of the palace area out of the queen’s lodgings, she passed through the Coldharbour gate and around the White Tower to arrive at the Green before the “House of Ordnance.” This was the place where the king’s soldiers often practiced archery and shooting, and where a “new scaffold” had been hastily erected—for today the killing would be real.

No more than three feet high, the scaffold was mounted by four or five steps. It ought to have been draped in black canvas, but whether the Tower officials had managed to do this in time is uncertain. Around it ranged rows of hastily constructed seating for the more important spectators, notably Anne’s stepson, the seventeen-year-old Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, the king’s illegitimate son, perhaps there to represent his father. Anne had treated Fitzroy badly, and he was going to enjoy seeing her die. Close by sat the Duke of Suffolk, Sir Thomas Audley (the Lord Chancellor), Cromwell and most of the king’s privy councillors, supported by members of the House of Lords. Behind them sat the Mayor and Aldermen of London, with the leaders of the city’s livery companies, headed by the Master and Wardens of the Mercers’ Company, further back craning for a view. A Tower official noted that many of the London contingent brought their wives and that, despite the strict prohibition, some “strangers” (i.e. foreigners) had managed to slip through the cordon. One of Cromwell’s future servants said, with pardonable exaggeration, that a crowd of a thousand had gained entry. More likely it was around half that number.

Once Anne reached the foot of the scaffold, Kingston led her up the steps. By now it was almost 9 a.m., and as was the usual protocol, he gave her permission to speak briefly. Audiences had fixed opinions as to what condemned prisoners should say. They were to make peace with their accusers and the world by confessing their faults, trusting in the mercy of God, asking the crowd to pray for them and then dying bravely. Obedience to the king’s will and submission to his justice was expected. No one was allowed to question the justice of their sentence or impugn the king—indeed, it was customary to praise him as a just and gracious lord. Above all, they should acknowledge that they were sinners, as all mortals were in the sight of God, and that they deserved to die.

Anne was not someone to conform blindly to the rules if she did not feel they were right. Barely three weeks before, she had been the most influential woman in the country. Advancing to the edge of the scaffold “with a goodly smiling countenance” to address the crowd, she unburdened herself of the lines she had carefully prepared:

Good Christian people, I am come hither to die, for according to the law and by the law I am judged to die, and therefore I will speak nothing against it. I am come hither to accuse no man, nor to speak anything of that whereof I am accused and condemned to die, but I pray God save the king and send him long to reign over you, for a gentler nor a more merciful prince was there never: and to me he was ever a good, a gentle and sovereign lord. And if any person will meddle of my cause, I require them to judge the best. And thus, I take my leave of the world and of you all, and I heartily desire you all to pray for me. O Lord, have mercy on me, to God I commend my soul.

What stunned the crowd into silence was not what she said, but what she failed to say. She offered no public admission of sin, no confession that she had wronged her husband, not even a hint that she was guilty of the crimes against God and nature of which royal justice had convicted her. One seventeenth-century reader, after transcribing her words in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, annotated them as “The queen’s oracular and ambiguous speech.”

The speech over, Anne’s ladies removed her mantle but left her wearing her gown. This was possible because the fashionable low square neckline would not have impeded access to her neck. Taking off her gable headdress herself, she tucked her hair into a coif. She next fastened “her clothes about her feet,” ensuring that if her skirts moved, her legs were not visible. She then “knelt down upon her knees.” Her only visible sign of emotion was to glance over her shoulder several times. Was this an understandable moment of fear, perhaps that the headsman would strike before she was ready? Or was it more poignant? She had previously told Kingston that though she had been harshly treated at the time of her arrest: “I think the king does it to prove me.”

Did she hope against hope for a last-minute reprieve? Was she looking over her shoulder for a messenger? Henry had the power to spare her—if he chose to. Although she had been in France at the time, she cannot but have heard of the king pardoning some 400 prisoners taken after the so-called “Evil May Day” uprising in London in 1517, when the houses of Italian and other foreign merchants were looted and burned. While twenty men were sent to the gallows, the rest, dressed only in their shirts and with halters already around their necks, knelt before the king in his full majesty in Westminster Hall. When they begged for mercy, Henry allowed himself to be persuaded into granting it. He waited until the last possible moment and would do the same a mere six days after Anne mounted the scaffold in the case of a friar known as “Peretrie.” It had already been decided to pardon him, but, theatrically, Henry ordered that “the law should proceed upon him even till the last point of execution.” Only as the hangman was about to kick the ladder away from the gallows would a messenger arrive with the letters of pardon. But if Anne dreamed that her former lover would save her, she barely knew him.

None of Henry’s queens is etched into the popular imagination so deeply as is Anne.

There was no need for a block since Anne was to be killed not with an axe, but with a two-handed sword in the French manner. For a beheading to go smoothly, it needed someone skilled enough to sever the head with a single blow. In Henry’s England, unlike in France, the common hangman wielded the axe. Because such men had more experience with the grislier tasks of hanging and “drawing” (i.e. disembowelling) their prisoners before cutting off the head and quartering the corpse, they often bungled beheadings, leaving dying victims in agony until a final stroke killed them. Commonly the hangman used his axe as a meat-cleaver to hack through the more obstinate sinews.

Anne did not have to face these horrors. Possibly as a last concession to the woman he had once called his “own sweetheart,” or perhaps as a sardonic reminder of her love of France, Henry had sent to Calais for a specialist headsman said to be an expert with a two-handed sword. At a price of 100 gold crowns of the sun (over £23,000 in modern values), the man would not come cheaply.

While one of her ladies placed a blindfold over her eyes, Anne said repeatedly, “To Christ I commend my soul; Jesu, receive my soul.” Those words were the executioner’s cue. On hearing them, his sword hissed through the air and he sliced off her head with a single blow. Sir John Spelman, one of the royal justices present, who confided his impressions to his private notebook, says, “He did his office very well…the head fell to the ground with her lips moving and her eyes moving.” A French report adds the blow came “before you could say a paternoster [Lord’s Prayer].” Nothing is said about the crowd’s reaction beyond that she died “boldly,” but it is hard to believe they did not gasp. Anyone who harbored doubts had to mask them. No one dared grieve openly for the dead queen lest they share her fate. Henry’s conscience was clear: she had paid, quite rightly, for her wickedness and treachery.

As soon as her head was off, one of the women threw a linen cloth over it, while the others wrapped the body in a bedsheet. They then carried the body with the head some seventy or so yards along the path to the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula at the north-west corner of the site. Inside the chapel, Anne’s clothing was stripped off—the Tower officials claimed her valuable fabrics as perquisites—before the women laid the corpse in an elm chest which had once contained bow staves destined for Ireland. Someone had perhaps forgotten, or more likely not dared, to attempt to measure Anne for a coffin, so the elm chest became a substitute.

At noon, the coffin was buried without ceremony under the floor of the chancel in the chapel beside the high altar. There she lay undisturbed until 1876 when, during restoration work, human remains said to be hers were exhumed at the request of Prince Albert, who ordered the bodies buried there to be properly identified and reinterred with name plaques. At a depth of two feet, bones were uncovered, said to belong to a woman in the prime of life, and of moderate height. The forehead and lower jaw were small and well formed. The skeletal vertebrae were unusually petite, especially one joint (the atlas) next to the skull, which the onlookers said was testimony to Anne’s “little neck.”

Henry famously had six wives: “Divorced, beheaded, died; divorced, beheaded, survived’ is a jingle that schoolchildren learning about them chant around the world. Why, of all these relationships, does this one bear fresh scrutiny? Part of the answer is personal and political: with none of his other wives would Henry rekindle the intense passion, and genuine respect, he felt for this one woman. For the love of Anne, he alienated his family, many of his courtiers and his subjects; for her he destroyed and even killed men whom he had once regarded as his supporters and friends; for her he broke with the pope, used Parliament to enact matters that affected people’s faith, ended centuries of tradition and risked war in Europe.

The other part of the answer is cultural and psychological: none of Henry’s queens is etched into the popular imagination so deeply as is Anne. Her story exerts a perennial fascination and is the inspiration for countless biographies and works of fiction, for plays, poems, films and websites, even for a Donizetti opera. Anne Boleyn costumes, dolls, necklaces and rings are sold online. Hever Castle’s shop offers an Anne Boleyn rubber bath duck in a French hood. Hers is a story that everyone thinks they know; and yet, do we fully comprehend who she was and what she stood for, and if so, how do we set about understanding why a man who was so besotted that he could hardly bear to be away from her for more than an hour could calmly summon a swordsman to strike off her head and believe himself to be in the right?

____________________________

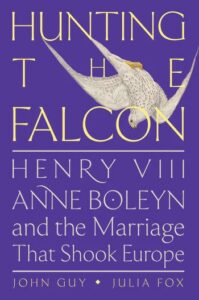

Excerpted from Hunting the Falcon: Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn, and the Marriage That Shook Europe by John Guy and Julia Fox. Copyright © 2023. Available from Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

John Guy and Julia Fox

Formerly provost and history professor at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, Renaissance historian John Guy is now a fellow in history at Clare College, University of Cambridge. He has written several books, including a best-selling textbook, Tudor England, and consults for the BBC.

Julia Fox is an author and historical researcher, and a former teacher. She lives in London with her husband, the Tudor historian, John Guy. Her first book was Jane Boleyn: The Infamous Lady Rochford, a study of the lady-in-waiting at the court of Henry VIII of England and the sister-in-law of Anne Boleyn