How Ancient Receipts Ushered in the Dawn of the Written Word

Moudhy Al-Rashid on the Earliest Forms of Writing

If the birth of history happens when people begin to write things down, then our own journey must start with the first written words in ancient Mesopotamia. It was with these first words that my own path into the field began. I have always been a bit of a nervous wreck, and as an academic it took years before I grew comfortable enough to deliver a talk in anything but a soporific monotone that could lull even the most over-caffeinated student to sleep.

When I managed to land a teaching job at Oxford University, I had to face my new reality of lecturing to an audience multiple times a day, every single day. My first few days were a sweaty, red-cheeked, nervous-stomached nightmare, until one class reconnected me with the clay tablets that had inspired me in the first place—tablets that happened to showcase some of the first words ever written down.

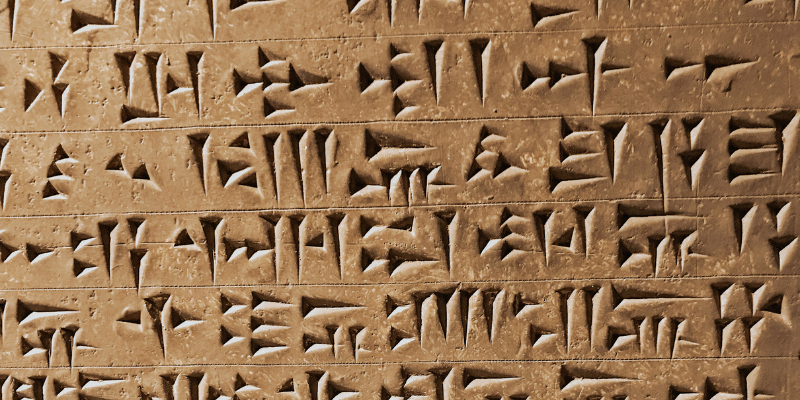

My anxiety followed me up the stone steps to the main entrance of the Ashmolean Museum one cool October morning, where four columns rise up several storeys from the stone slabs of its courtyard. I found my students at the building’s side entrance and led them to the study room where two blue trays of cuneiform tablets awaited us on a large table topped with black foam. It took less than a second for the rush of adrenaline at seeing the tablets to sweep away all of my nerves. Before us lay some of the earliest examples of writing in all of humanity’s history.

It was now my turn to teach others about these moments from the dawn of writing, frozen into lumps of clay and nestled neatly in a bright blue plastic tray.

We took our seats around the table in awed silence. I picked up a pale, iPhone-sized tablet whose surface was divided into uneven boxes, some filled with thick dots and others etched signs—a sheaf of barley, a foot, a bull, a divine star. “Let’s start with this one,” I said, recognising what was essentially a very ancient receipt tallying up as many as 400 objects. This was, after all, one of the first tablets I had ever picked up years ago as a student in this very class. It was now my turn to teach others about these moments from the dawn of writing, frozen into lumps of clay and nestled neatly in a bright blue plastic tray.

Amazingly, tablets from this early era of the first attempts to codify a writing system share features with those made by scribes thousands of years later, like the scribe who made the drum-shaped clay museum label from the palace of Ennigaldi-Nanna. In the seventh century BCE, a generation or so before the princess was born, that scribe, called Nabû-shuma-iddin, was pressing a reed stylus into a lump of wet clay. He pinched, rolled, and shaped the slightly slippery, moist clay to form a small cylindrical tablet about four inches long and two inches in diameter. This drum-shaped piece of clay would fit comfortably into the palm of my hand, solid and smooth apart from the gentle texture of impressed signs.

The landscape’s wealth of clay helps to enable the birth of the written word.

Nabû-shuma-iddin covered the drum in signs describing the now missing brick of King Amar-Suen. His text leaves behind such a wealth of detail that we need not feel too wistful about the lost brick, which once bore a short inscription in Sumerian, the first known written language used by the people who lived in what is now southern Iraq. The brick, Nabû-shuma-iddin tells us, had been discovered by Sîn-balassu-iqbi, a governor of Ur in the seventh century BCE. In other words, he was recording an archaeological find by one of his contemporaries, much as any archaeologist today makes notes on an ancient artefact and the circumstances of its excavation.

This little drum can unlock for us far more than the possible nature of Ennigaldi-Nanna’s collection. It also reveals an interplay in ancient Mesopotamia between history and languages, the shared script of cuneiform, and the main medium on which these have survived: clay. Clay may not look like much. Damp and a bit sticky when wet, it can be grey, beige, brown, or a slightly more exciting reddish brown. This ubiquitous material left the soil in ancient Mesopotamia so rich with nutrients that some people call this land between two rivers the “fertile crescent.” This silty soil may seem insignificant at first, but it becomes the opener for a major chapter in humanity’s ongoing global story. The landscape’s wealth of clay helps to enable the birth of the written word.

Nabû-shuma-iddin, a professional scribe, would have spent only a few minutes shaping the wet clay of the cylinder, but would have taken considerably longer to cover it in writing that would have been ancient even to him. On the clay cylinder are four columns of text, written in two different styles of cuneiform script. The first three columns preserve a style deliberately made to look old, just as the “font” would have appeared on the original brick he was copying from: an attempted rendition of the original Sumerian writing on the brick of Amar-Suen.

Although kept alive in scholarly settings, much like Latin was in medieval Europe, Sumerian was no longer spoken in ancient Mesopotamia after about 2000 BCE. Nabû-shuma-iddin would have had to learn it in school, and when he copied the ancient text, he also copied the font style, like we might use a Gothic font to evoke an older text. The signs are so large and elaborate that only a few—sometimes only one—fit on each line. The fourth and final column uses the contemporary and far more streamlined Babylonian style of cuneiform to describe how Ur’s governor found the brick.

To give you an idea of how different these two styles look, the cuneiform sign lugal, which means “king,” uses seventeen wedges in ancient Sumerian, whereas the later Babylonian version of the sign uses only seven. To see two such script styles from totally different eras in a single work is odd. It would be like using American Typewriter font for contemporary newspaper quotes in a history of the 1960s space race—or even like using cuneiform-like letters in this book’s quoted passages from ancient tablets. Nabû-shuma-iddin reprised an archaic style of writing to remain as faithful as possible to the original inscription on the brick he was copying from.

This object captures perfectly the many layers of meaning, language, and history embodied in cuneiform and clay. The cuneiform on the clay drum is itself a museum of Mesopotamia’s past—each character contains layer upon layer of history. The individual characters of a writing system in use for thousands of years are bound to reflect stages of history. Each period of cuneiform’s use had a unique font style, as well as a language or dialect typical of the era, and even preferences in the signs and words used. Where Shakespeare wrote ‘doth’, today we say “does” and what we call “chaos,” he called “coil”; it may be the same language, but his word choice fitted his era (and genre). Cuneiform, like any writing system, also evolved from one era to the next, as did the languages it was used to write. Each individual character offers us a window onto the past.

One of the first clay tablets I ever held in my hands was the iPhone-sized one at the Ashmolean Museum that I picked up again, many years later on that nervous October morning. On one side of the small clay slab, uneven boxes contain a series of what look like tiny pictures. One character resembles a boot, another looks like a star, and another might be the head of a bull. The other side of the tablet is a different story; it shows a scattering of dots and two other carefully drawn signs—it is a calculation, showing the sum total of all the things pictured on the reverse of the tablet.

This ancient accounting record comes from the early period of cuneiform, which ranges from the Late Uruk period from about 3500 to 3000 BCE to the Jemdet Nasr period from 3000 to 2900 BCE, named for the city of Jemdet Nasr where similar developments occurred around the same time. (In fact, this tablet was from the city of Jemdet Nasr.) In its early form, cuneiform signs often looked like the things they represented—a boot might represent something like walking, a star might represent something divine, and the head of a bull might represent that animal.

And this is how not poets or artists or philosophers, but rather middle managers brought about the birth of writing.

It felt intimate to cradle that tablet in my palm, like I was touching the unknown, early scribe who also once held the wet clay while tracing pictures of boots and bulls into it. Over time, these realistic signs were streamlined and simplified until they could be impressed rather than traced into clay, creating the distinctive wedge-shaped writing we call cuneiform at the beginning of the third millennium BCE. As the English word “cuneiform” refers to the script’s visual appearance (from the Latin cuneus, “wedge”), so too does the Arabic word mismari, which derives from the word for nail. The signs, in other words, look like the marks left behind by nails. The Akkadian word for the script, sattakku (or santakku), also describes its appearance; it means triangle.

Because cuneiform has evolved in various stages, it is relatively easy to date a tablet based on the writing style alone, even with no knowledge of the language being recorded. Very ornate signs that resemble the objects they represent make it easy to date an object to the early days of cuneiform, while characters that look more like nail prints, wedges, or triangles are a clear giveaway that they are a later version of the script used by people like Nabû-shuma-iddin and even Ennigaldi-Nanna.

To understand the beginnings of writing in clay, we must travel three millennia back in time from even Ennigaldi-Nanna’s era and 13 miles from her palace in Ur, upstream on the ancient course of the Euphrates to a city called Uruk. There, another ziggurat rises out of the sand like a camel’s hump, and today at its foot is an unassuming blue sign bearing two lines of white Arabic writing that state: “The first written words started here.”

What may surprise (or even disappoint) you is that the motivation to create these first written words came not from a deep-seated need for self-expression, but from a far more practical need to record—in essence—who owed beer to whom, and how much. Around 3350 BCE during the Late Uruk period, in the city of Uruk, a man named Kushim (or at least, this is our best guess at how to say this name) was in charge of a storage facility for the basic ingredients of beer production. Almost all texts signed by him concern the two products used to brew all known beer types of this time: malt and barley.

Far from a DIY homebrew kit tucked into a basement in Portland, this was an enormous undertaking and a critical cog in the administrative machinery of agriculture in Uruk. At one point, Kushim had to administer 135,000 litres of barley over the course of thirty-seven months, and at another, he was responsible for the production of nine different cereals used to make eight different kinds of beer. This beer provided rations to agricultural workers who harvested products that were stored and redistributed by the temple, which served as the city’s religious and economic centre.

Fertile soil and new farming methods increased the number of products for Urukeans like Kushim to keep track of, a phenomenon sometimes known as surplus agriculture. Uruk had a distributive economy, where these agricultural products were funnelled through the temple to its workers and a wider population. Already, one byproduct of successful agriculture becomes readily apparent: the need for middle managers. The sheer volume of stuff being produced triggered a hierarchy of personnel and became a highly bureaucratic affair. People like Kushim managed the products harvested by the people he oversaw and the payments for those people’s labour in rations, and he likely answered to someone else higher up the administrative chain.

And this is how not poets or artists or philosophers, but rather middle managers brought about the birth of writing. Imagine being Kushim and having to keep tabs on all of these goods in your head. Most of us would lose track pretty quickly, even instantly in my case as I cannot even remember someone’s name within seconds of meeting them, let alone something more complicated like their phone number. Administrators needed some kind of memory aid, which initially took the form of little clay tokens to count and keep track of commodities like barley, oil, sheep, and textiles.

These tokens have been found at numerous sites throughout the ancient Middle East, from Turkey in the north all the way to Iran in the east. As methods for counting and accounting, they may have been used as early as 7500 BCE—almost 10,000 years ago. But around 3500 BCE, a rise in the number of commodities being represented signals an uptick in the goods being produced and distributed, and the reliance on tokens to keep track of them.

These early tablets may not seem like much, but they represent a major leap in the development of a technology without which this (or any) book would not be possible: writing.

Some tokens were miniatures of the objects they represented. Complete with a handle just big enough to be pinched between one’s forefinger and thumb, a tiny jug found in Uruk represented oil, and a slightly different tiny jug represented beer. They are so adorable that you’d be forgiven for thinking they could be toys instead of an elaborate clay calculator. Other tokens were more geometric than naturalistic. In Jemdet Nasr, tokens had a variety of geometric shapes. Instead of a tiny jar, an ovoid token represented a jar of oil, a disc represented sheep, and a cone-shaped token represented a small measure of barley. Sometimes, these shapes bore markings, like lines and dots, that provided further information about the object being counted.

Regardless of their shape or place of origin, a few of these could comfortably fit into the palm of your hand, like Monopoly board tokens, and were sometimes stored in spherical clay envelopes impressed with markings on the outside to reflect their contents. These envelopes were sometimes imprinted with a seal that added a layer of security and authenticity to the information they contained, sort of like a wax seal on an envelope.

Eventually, things shifted from three-dimensional tokens and envelopes to two-dimensional signs incised into pillow-shaped clay tablets. Traced with the sharpened end of a reed stylus, these signs looked a lot like the things they represented, such as a bowl for food or rations, genitalia for the sexes of workers, and a jug for milk or beer. The early administrators pressed the opposite, unsharpened end of a stylus into clay to represent numbers. Instead of representing thirty jars of oil with thirty ovoid or jug-shaped tokens, for example, a picture of a jar was traced into clay to represent “jar of oil” and preceded with three impressed dots that could represent the number 30. As with the tokens, there is a limited repertoire of things being recorded, all of which include people, products, animals, and commodities related to agriculture. These early tablets may not seem like much, but they represent a major leap in the development of a technology without which this (or any) book would not be possible: writing.

Writing and agriculture were so closely intertwined that the Sumerian goddess of grain, Nisaba, eventually also became the goddess of writing and patron of scribes. A hymn to her, written down much later than these early tablets and tokens, opens with a dazzling description of the goddess and a tool of her trade: “Lady coloured like the stars of heaven, holding a lapis-lazuli tablet.” “May you be the butter in the cattle-pen, may you be the cream in the sheepfold, may you be keeper of the seal in the treasury,” it reads.

A seal may seem out of place in a poem about the goddess of writing. It refers (tragically) not to an adorable marine mammal housed in the treasury, but to an administrative tool that served an integral role in temple accounting. About the size and shape of an AA battery, these cylinder seals were carved with imagery and, later, minute inscriptions that said something about their owner, like an ancient social media avatar. Instead of a photo of me with a dog and a bio that described me as a historian and dog lover, for example, I might have had a cylinder seal engraved with the image of the Mesopotamian healing goddess Gula, depicted with her pet dog. The seal may have included an inscription with my name, patronymic, and occupation.

Carved from a variety of stones, seals said something about their bearers and even about the tablets that they were gently rolled onto to impress the delicately carved scenes and sometimes cuneiform signs. A “sealed” tablet conferred an added layer of authenticity to the document. Like an official letterhead that graces the top of old-school paper correspondence, or a signature at the end of a legal contract, a sealing carried the authority of the sealer, affirmed their identity, or verified a transaction.

These small battery-sized objects radiate a totally unexpected beauty for what is more or less an ancient e-signature. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, which tells the story of a legendary king’s quest for eternal life, there is a scene where he emerges from a pitch-black tunnel, past even where the sun rises and sets, onto a “garden of the gods” where jewels stud trees that are made out of precious stones. “A lapis lazuli tree bore foliage,” reads one line, “in full fruit and gorgeous to gaze on.”

I find this really moving—that the landscape itself made this leap in human innovation possible, that ingenuity worked in tandem with geology to change the course of history.

Others glowed with rich red carnelian, coral, and even the metallic sheen of haematite. To me, cylinder seals from ancient Mesopotamia are so “gorgeous to gaze on” that they look like they could have been plucked from the trees in this divine garden at the edge of the known world. A dark green cylinder seal, as old as the earliest writing in ancient Mesopotamia, shows two people holding back a bull that appears to have broken loose from something. Its horn curves above its head like a long crescent moon, and below it a minute eye—no bigger than perhaps a millimetre or two—stares dead ahead. It drags two lines of rope behind it, depicted down to perfectly spaced knots. A tiny lapis lazuli cylinder from several centuries later glows with such a bright blue it looks like it contains a whole ocean. Three bearded figures wrestle two lions in a stylised scene that looks more like a dance than a hunt. Their muscles ripple with the effort, and innumerable little lines make up the lions’ manes. The artistry takes my breath away, even if their function might have been as mundane as a signature or Instagram bio.

Together, seals and early writing provided the much-needed bureaucratic tech to meet the growing demands of agricultural production and distribution in the last half of the fourth millennium BCE in the fertile plains of southern Mesopotamia. The same circumstances that made the soil fertile enough for agriculture to thrive also left behind the clay that became the medium for recording the fruit of that soil. I find this really moving—that the landscape itself made this leap in human innovation possible, that ingenuity worked in tandem with geology to change the course of history.

These early tablets were perhaps once kept in baskets or on shelves, and were likely discarded after the clay receipt or record was no longer needed, much like I don’t think twice before throwing away a Tesco receipt. But like many ancient artefacts, their final resting place was not the place they were originally used and kept. If every object has a story, these earliest examples of writing began as wet clay in the hands of agricultural administrators like Kushim and ended, for the most part, in the trash.

About 5,000 of these early clay tablets were found during modern excavations in the 1950s in a district of Uruk known as Eanna, meaning “House of Heaven,” which was the beating heart of the city’s agricultural administration. An architectural layer cake of Uruk’s economy, religion, and scholarship, the Eanna district housed temples built alongside and on top of one another, beginning with the earliest monumental architecture of the fourth millennium BCE. Constructed from mud bricks, the temples and terraces of the Eanna would have been an enormous logistical undertaking.

One building, charmingly named Building C by modern archaeologists and constructed in the same period that saw the development of writing just over 5,000 years ago, had walls 16 feet high and required over one million bricks to construct. It was one of the largest buildings from this period in Uruk’s history. When Building C and nearby structures were originally built, surface pits were dug to lay their foundations. Today, one would expect a truck to pull up to such a cavity and slowly fill it with concrete from a revolving mixer. In ancient Uruk, the pits were filled, instead, with garbage. Cheap and accessible, it made for excellent foundation material. Animal bones, pottery fragments, ash, broken mud bricks, and some of these early proto-cuneiform clay tablets found their way into these pits below the monumental architecture of ancient Uruk.

Ancient trash preserves not just everyday life from 5,000 years ago, the ancient analogues of my Amazon packaging and yogurt pots, but also milestones in human history—in this case, the earliest attempts at a brand new technology called writing. Because the tablets were used as fill for buildings that were constructed around 3200 BCE, archaeologists assume that they must have come from the preceding period in Uruk’s architectural layer cake, anchoring the earliest attempts at writing to around 3350 BCE. As far as we know, this is about 200 years before hieroglyphs develop into a writing system in neighbouring Egypt and 2,000 years before the earliest evidence of writing in China.

These tablets from the end of the fourth millennium BCE show that writing did not emerge fully formed overnight, and that it was developed not to write sonnets, but receipts. Tokens, their clay envelopes, and stone seals set the stage for the technology that would ultimately make it possible to write anything down, from these early receipts to later letters between kings and lullabies to comfort a crying baby.

__________________________________

From Between Two Rivers: Ancient Mesopotamia and the Birth of History. Used with the permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company. Copyright © 2025 by Moudhy Al-Rashid.

Moudhy Al-Rashid

Moudhy Al-Rashid is an honorary fellow at the University of Oxford's Wolfson College, where she specializes in the languages and history of ancient Mesopotamia. Originally from Saudi Arabia, where she grew up, she now lives in Oxfordshire with her family and their dogs.