How an Exile's Return to Iran Inspired a Novel

Donia Bijan Visits Her Childhood Home

Strange things happened when I returned to Tehran in 2010 after 32 years in exile. Arriving past midnight, when many of the international flights land, I sipped lukewarm coffee while waiting for my bags. Seated together on a nearby bench, two sleepy looking toddlers were draped across their mother’s lap. Another boy clutched a game device; a woman plunked down beside him and checked her watch. Perfect strangers looked familiar. This was Imam Khomeini Airport—his glowering portrait there to remind us—but it was no different from LAX or Charles de Gaulle or Heathrow. I understood the PA announcements, the monitors, the restroom signs, and the currency exchange booths. I felt safe in this neutral zone, imagining boarding another flight on a whim. I was born here, yet I had no idea what sort of place lay outside. Was it still the city of my youth?

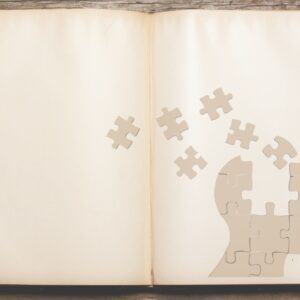

My sisters and I had arranged for a driver to pick us up. Seeing the sympathetic face of a young man holding a placard with our last name on it in Persian script was deeply endearing, as if he had taken special care to write bijan. This was a homecoming, but we had no place to go, no family to come back to. Did I really think that the house where I grew up, seized post-revolution by the regime, would be returned to my family? No. But, emboldened by smooth talking mediators who stood to gain from the transaction, we had come to try.

What I found most striking in the first 24 hours was how I felt constantly close to tears. At the small family-run hotel, upon answering a call to our room from the front desk, I came undone when I heard “Good morning, Khanoom Bijan” (Mrs. Bijan). Khanoom? No one had ever called me that—I had left Iran at 15, too young to be a Mrs. How beautifully she pronounced my name. “Yes! Yes, it’s me, Khanoom Bijan,” I announced, with such exuberance that the caller probably thought she was disappointing me with such ordinary news that breakfast was served until 10 am.

The first thing we did was ride a taxi through unrecognizable streets in search of our house. Along an avenue that was once named after my father for the hospital he built in the 1950s, on yet undeveloped land, was a low building set far back, a quiet relic of old Tehran. If it weren’t for the gate, we would have missed it altogether. How many dreams were interrupted by husbands pounding on that very gate beside their pregnant wives in labor, howling in the night for Doktor Bijan? We stood before the hospital where I was born, where our family had lived on the top floor, the building my father built brick by brick. Here was where my parents delivered thousands of babies. Here was the yard where we buried our dog Sasha, and here was the pool where I learned to swim.

Finding the gate unlatched, we ventured inside. Turf now covered the pool. Bath towels, green and blue, hung from the upstairs balconies, furling and unfurling, seeming to taunt us as we gazed from below at our girlhood bedrooms, holding back our tears. The caretaker emerged from his cottage to shoo us away, shutting the gate in our faces.

By the third morning, still jet-lagged but anxious for exercise, I threw a swimsuit in my backpack and set out for a local pool that was open to women a few hours a week. I left the hotel with the vague idea that I’d blend in wearing a knee-length sweater over jeans, covering my hair with a scarf that periodically slid off my head. I observed other women walking by in stylish manteaus with cinched waists worn over tailored pants. Above their charcoal-rimmed eyes, their hair was swooped into a cone at the crown and wrapped in elaborate head scarves. I looked every bit the foreigner with my oafish backpack.

I approached the façade of a building covered with a dark panel of fabric. Even the door had to wear a cloak for ladies’ hours. I pushed the cloth aside to enter and stood for a moment to breathe the saturated scent. As a swimmer, I am fond of the thick smell of chlorine. Standing in the front office was a pretty young woman, her hair unraveled, holding a loaf of bread. While I paid the entrance fee, my eyes wandered past her bare shoulder to the voices behind the desk. Two attendants sat at a small table, waiting for their colleague to join them. A kettle whistled. It was still early, and I had interrupted their breakfast, the rare moment when they could sit, unencumbered by veils, rules, and threats, to eat and chat freely. Yet here was their first customer with only one selfish thought—to tear her silly scarf off and swim laps. I rushed into the changing room, apologetic but filled with an intense desire to sit with them, feeling such affection for them, wanting to know what kind of lives they led. My middle-aged American self was already snapping goggles in place, while the Persian girl who left long ago wondered if they might call out to her, if they had saved her a seat. I shivered at the edge of the outdoor pool while a voice inside my head told me to throw myself in. For a few seconds, with my head under water, I pushed through, giving it my all. Gasping when I reached the wall, I looked up at the sky, my head buzzing with thoughts. Yes, I may have lost my footing in Iran, but I still felt like I belonged, regardless of who occupied our house or how far I had traveled.

I have never felt closer to strangers than I did during the women’s hour at that pool. Long after I returned to America, I could not get the image of the three women at their breakfast table out of my head. Like a baton in a relay race, they slipped a clue into my hands—I was both sister and stranger. I ran with it and began writing.

I gave the women names—Ferry, Bahar, Sahar—imagined their triumphs and heartaches, and created a connection between them and an outsider returning from exile to Tehran, her birthplace, who brings along her very American daughter. A cook by profession, I reconstructed the beautiful ruins of my city as a beloved café. To write about such a place was to enter troubled waters, for I did not want to mitigate the grim and gruesome side of the world beyond the café but bear witness to loss, explore how people behave in the shadow of fear and mayhem. Who turns a blind eye to the atrocities that erupt on the streets, and who shows courage? It so happened that my characters were open to a whole world of possibility. Café Leila became a place of refuge, where outsiders form a kind of family, where someone saves you a seat.

I knew when I put my face to the gap in the hospital gate that I would never see my childhood home again, but my return to Tehran was not a futile journey. Daughter, what took you so long? I imagined hearing from the very soil. It is my hope that as you read The Last Days of Café Leila, you will feel the same sense of place that I felt during the women’s hour and experience belonging in a new and unexpected light.

Donia Bijan

Donia Bijan is a San Francisco Bay Area chef who left Iran in 1978 during the Islamic Revolution that threatened the life of her mother, an outspoken women’s rights advocate. After graduating from UC Berkeley, Donia went to Paris to attend the Cordon Bleu. In 1994, she realized her dream of opening her own restaurant, L’Amie Donia, a celebrated French bistro in Palo Alto, California. Since closing her restaurant, Ms. Bijan has divided her days between writing and teaching. Ms. Bijan lives in Northern California with her husband, the painter Mitchell Johnson, and their son.