How America’s First Nonbinary Minister Created True Equality in the Newly Born United States

Nina Sankovitch on “Universal Friend,” the Genderless Messenger of God Who Aimed to Save Lost Souls and Preach Universal Salvation

In the spring of 1776, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, John, asking him to “Remember the Ladies” as he and the other (all male) representatives to the Continental Congress debated the path to American independence. Abigail hoped that when the colonies achieved independence, women in America would join in the victory and finally have a say over their own lives without having to bow to the authority of men in managing their homes and property, and planning for their futures. But John Adams scoffed at Abigail’s hopes, writing back to her, “I cannot but laugh Depend upon it, We know better than to repeal our Masculine systems.”

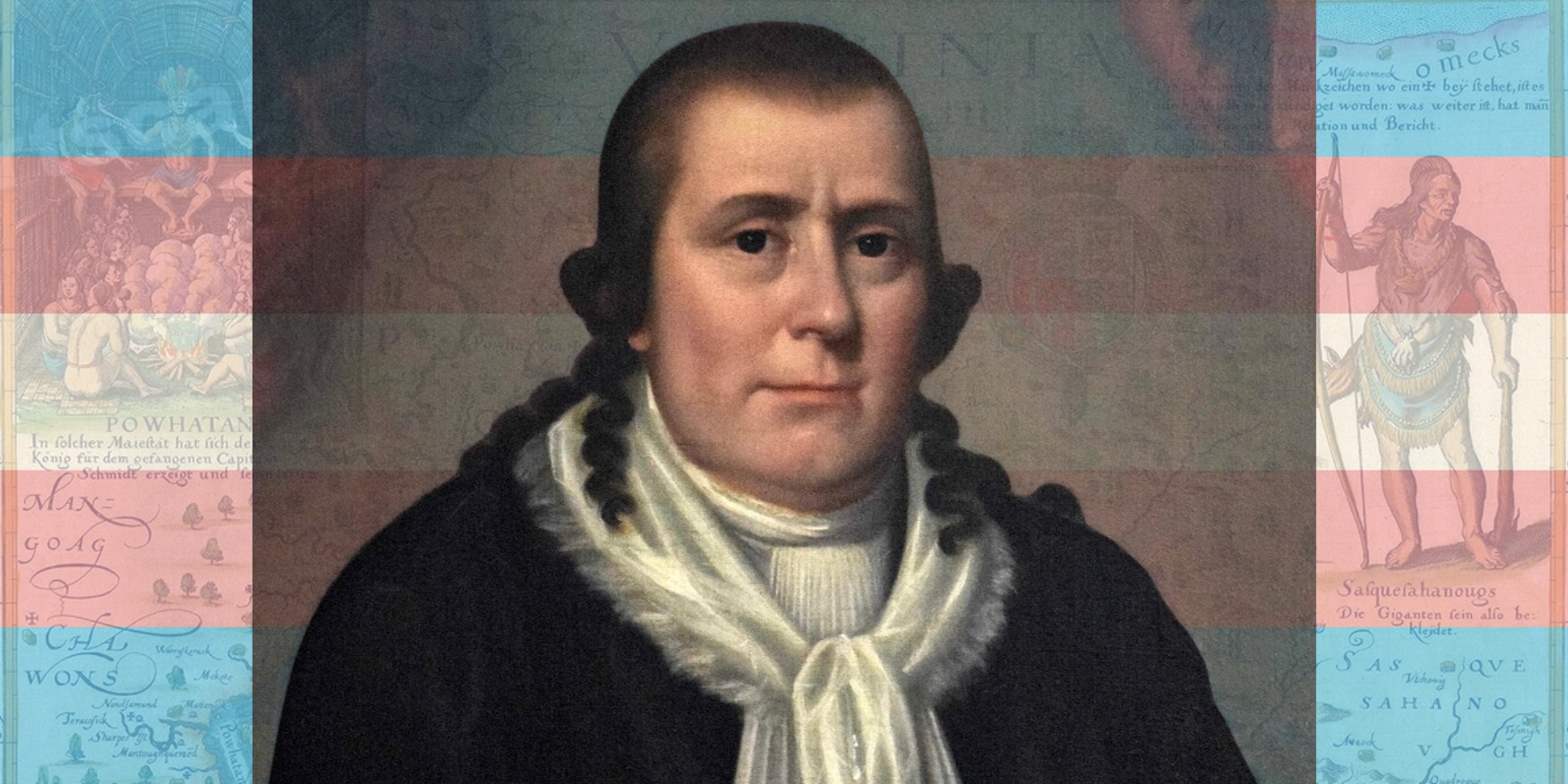

In October of that same year, a young woman from Rhode Island named Jemima Wilkinson claimed to have died and been reborn as a genderless messenger sent by God to save lost souls. Adopting the name “Universal Friend,” within months the minister was preaching a message of universal salvation to crowds throughout New England. Universal Friend would become the first American-born founder of a religious sect, and the country’s first nonbinary minister.

But perhaps most importantly, in the decades following America’s independence from England, Universal Friend established communities in which Abigail Adams’s hopes were realized. Hundreds of followers from all walks of life, men and women, Black and white, lived as equals under the minister’s leadership. Freed from constrictions based on race, class, or gender, they pursued dreams of social stability, economic prosperity, and shared piety—and made those dreams a reality.

Universal Friend did what men like Washington, Jefferson, and Adams had promised: created a society that valued equality, promoted opportunity, and fostered a flourishing economy based on individual enrichment while also emphasizing working for the common good.

What first drew me to the story of Universal Friend was the minister’s refusal to be identified as either male or female, instead insisting, “I am that I am,” and adopting a genderless name while also dressing in androgynous clothing. But as I delved deeper, I became fascinated by how the story of Friend’s life illustrated the story of the United States during the years of the American Revolution and the decades following independence. By looking closely at individual lives during specific times in history, we can learn so much about larger historical events and themes.

The life of Universal Friend proved to be particularly illuminating, especially in how Friend established communities that embodied the ideals for which the American Revolution was fought, while elsewhere in the new nation of the United States those ideals fell woefully by the wayside.

Universal Friend did what men like Washington, Jefferson, and Adams had promised: created a society that valued equality, promoted opportunity, and fostered a flourishing economy based on individual enrichment while also emphasizing working for the common good. There is no denying that Friend was a religious zealot who had some very extreme ideas (which will be explored in this book).

Nevertheless, the communities founded by Universal Friend are proof of just how impactful the American experiment could have been if the promises of the Revolution—Americans’ inalienable rights to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”—had been kept. Universal Friend, for example, required followers to manumit their enslaved workers. While the total number of persons emancipated under Friend’s guidance remains unclear, just imagine what the United States would have looked like by the late eighteenth century if all the spiritual leaders in the country had required their congregants to manumit their enslaved laborers.

Universal Friend adopted the name, uniform, and grooming of a nonspecific gender.

The writings left behind by Friend are sparse, consisting of fewer than a dozen letters written by the minister; journal entries (largely consisting of copied-out favorite texts); an undated sermon titled “An Answer to Roxbury People”; some notes scribbled on loose papers; an undated “Meditation”; a memorandum recording the alleged transformation from a dying woman to the reborn messenger of God; and a pamphlet of “Advice” setting out the rules of the sect (some of which are inspiring and some of which are just strange).

There are also written records of Friend’s dreams, which the minister viewed as direct communications with God. But most of what we know about Friend—how the minister looked and behaved, preached and loved, created a ministry and inspired followers—is from the observations of others. Some of these observers admired Friend very, very much, and some most definitely did not. These observations are found in newspaper articles, pamphlets, and journals, and in dozens of letters and diary and journal entries written by eyewitnesses to Friend’s ministry.

Distilling the truth from the limited number of documents created by Friend and the often exaggerated or distorted tales recorded by others can be challenging. Universal Friend adopted the name, uniform, and grooming of a nonspecific gender. While one may question whether it’s appropriate to use the concept of nonbinary identity when discussing a person who lived over two hundred years ago, I believe there is no other accurate way to describe Friend’s gender identity.

Historians who have written about Universal Friend, as well as contemporary observers of the minister, largely conclude that Friend rejected identification by male or female gender: as reported in a Philadelphia newspaper following a visit of the minister to that city in 1787, Friend was not “supposed to be of either sex” and behaved and dressed in ways that underscored the state of “being neither man nor woman.” The LGBT Foundation defines as nonbinary “people [who] may identify as both male and female or neither male nor female. They may feel their gender is fluid, can change and fluctuate or perhaps they permanently don’t identify with one particular gender.”

The question, then, is which pronoun to use when referring to Universal Friend. Two previous books, Moyer’s biography and Pioneer Prophetess: Jemima Wilkinson, the Publick Universal Friend written by Herbert A. Wisbey, are both excellent studies of the life of Friend and proved very useful to me in writing this book. Neither, however, helped me in deciding which pronoun to use in referring to the re-born Jemima Wilkinson. Wisbey chose to use the female pronoun when talking about Universal Friend, while Moyer chose to use the male pronoun following the minister’s transformation in 1776.

In the times we live in now, the pronoun “they” might be appropriate. Letters and diary entries by devoted followers overwhelmingly refrain from using any pronouns in referring to the minister, and so I’ve chosen to respect what I believe was the practice of Friend’s followers (perhaps at Friend’s explicit directive) to use no pronoun at all when referring to the minister.

Friend’s underlying goal was one that Americans hold close to our hearts: How to create a practical, functioning utopia. A world in which all its citizens have hope.

In addition to illustrating the times in which Universal Friend lived, the minister’s story is compelling for how it relates to current debates over who we Americans are as a people and as a nation. In so many ways, Friend is an archetype of the American dream: a person who came from a modest background and managed to achieve wide-spread fame, influence, and prosperity. Universal Friend was independent, resolute, and brave—qualities that we Americans often claim as uniquely ours—but also stubborn and egotistical.

The minister exhibited all those characteristics in a lifelong effort to resolve many of the same issues with which we Americans struggle today, including the role of religion in society; how to balance self-determination and freedom with civic responsibility; how to offer equal opportunities to diverse participants; and the politics of identity. Friend’s underlying goal was one that Americans hold close to our hearts: How to create a practical, functioning utopia. A world in which all its citizens have hope.

Universal Friend believed that God had chosen Jemima Wilkinson’s body to serve as the vessel to be his messenger of salvation. Whether or not we believe it doesn’t matter; Friend did, and for forty-three years remained dedicated to the mission of salvation, while also challenging the status quo in just about every arena entered. How did a young Quaker woman from a sleepy village transition into an influential and charismatic force for change? From where did Friend’s ideals of equality and liberty grow? What were the political and cultural circumstances that allowed Friend’s sect to flourish? How did the minister find the strength to keep on going in the face of false accusations, slanderous press, treachery of trusted friends, deaths of beloved companions, the heavy burdens of natural disasters and decades-long legal proceedings, and against the tides of fickle public opinion and internecine dissent?

I hope you find the answers to these questions—and the remarkable story of Universal Friend—as wonderfully interesting and inspiring as I do.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Not Your Founding Father: How a Nonbinary Minister Became America’s Most Radical Revolutionary. Copyright © 2026 by Nina Sankovitch. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

Nina Sankovitch

Nina Sankovitch is the acclaimed author of the memoir Tolstoy and the Purple Chair and several works of popular history, including Not Your Founding Father. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and Vogue.