How America Remembers Emmett Till

"Hatred could not justify child murder, but fear could."

We think of memory as beginning in clarity then fading with time, but it is rarely so simple. Terrifying events get repressed while things that at first seemed fleeting or ephemeral grow in importance as the years pass. Conversations that felt inconsequential come flooding back, filled with new meaning. Remembrance of things past suddenly brings whole epochs into sharp focus. We reconstruct memories belatedly, imperfectly often through the needs of the present.

What is true for individuals is also true for whole cultures. Emmett Till’s name mostly vanished from print a few months after [William Bradford] Huie’s article appeared [in the January, 1956 edition of Look magazine]. One major newspaper database, for example, lists more than 3,000 articles about him during 1955 and 1956, the vast majority published in the six months following his murder. The whole of the 1960s brought only 300 articles. In the 1970s, fewer than 50 stories appeared. From there the numbers picked up slowly, almost 150 articles in the 80s, nearly 250 in the 90s. Then suddenly 2,000 in the first decade of the 21st century. Books take much longer to write and publish than newspapers, but something similar happened: a handful of books about Till in the 1960s and 70s, then a rising tide from about the mid-1980s all the way into the new century.

That the number of stories about Till declined sharply with time is no surprise. But given how big the story had been, it seems odd that there were so few remembrances of him on the tenth and 25th anniversaries of his death. It was as if those who wanted to put the story to rest after Sumner finally got their way—a willful erasure for some, an embarrassed silence for others. But not everyone forgot. Some remembered Emmett Till as the decades passed, a few fiercely so. Most unexpected was the awakening that came at the end of the 20th century and into the 21st.

The Emmett Till story stayed alive in the headlines through 1955, sometimes in unexpected ways. For example, turmoil engulfed the Chicago community of South Deering during the early 1950s, usually involving black families seeking to move into this white working-class neighborhood. South Side towns experienced riots, bombings, and assaults, and not just in Chicago, for such vigilante action bedeviled many segregated northern cities. Ten days after Till’s body rose, renewed tensions provoked an editorial in the Newsletter of the South Deering Improvement Association, an organization dedicated to keeping the town white. The editor praised Mississippi for controlling its black population and condemned as “brazen hypocrites” those upset by Till’s killing. In our “mongrelized city” the editor wrote, “thousands of White women, girls and even small children are raped and/or murdered by negroes each year.”

Behind the editorial was a long history of de facto segregation in Chicago, first on the South Side, then in a new West Side ghetto, all of it enforced at midcentury by federal housing laws, local ordinances, red-lining, restrictive covenants, “block busting” by corrupt real estate brokers, and banks refusing to loan to African American customers. Violent assaults against black families seeking to move into white neighborhoods were merely the end-game of institutional racism. South Deering offered a little reminder, should anyone need it, that all of the high-horse condemnations of the South masked the urban North’s own brand of segregation.

On the other hand, the Westport (CT) Town-Crier condemned the Sumner verdict [in which an all-white jury acquitted Emmett Till’s killers] but refused to turn criticism of the South into a praise song for the North. The Town-Crier editor declared that a small lynching occurred every time restrictive covenants kept black families out of neighborhoods, everytime African Americans were denied educational or employment opportunities, every time whites stereotyped blacks. It was as if the Town-Crier was taking direct aim at places like South Deering. Of course, Westport was a wealthy and distant suburb of New York City; the issue of African American families moving in was more abstract than in South Deering.

Throughout 1955, Emmett Till’s name evoked a range of responses from whites, North and South, all of them coming to grips with a world destabilized by mass African American migration, the budding freedom struggle, and changing ideas about equality. His story provided a way to think about these issues. But even before William Bradford Huie published his article in Look, Till’s name had begun to fade.

In late November, a friend of J.W. Milam named Elmer Kimbell murdered a black man in cold blood. Clinton Melton, father of four, had pumped gas and fixed cars at Lee McGarrh’s service station for ten years. Melton was highly respected. The Glendora Lions Club called his murder an outrage. A peace officer picked up Kimbell at J.W. Milam’s house. Kimbell showed a superficial wound and claimed Melton shot him first, overcharged him for gas, and then spoke abusively to him. McGarrh, a respected white business owner, witnessed the whole event, and swore in court there had been no improper language from his black employee, that Kimbell drove up drunk in Milam’s car (the two had gone hunting that day), and that the only gunfire came from Kimbell’s shotgun. The grand jury charged Kimbell with murder, and the judge (Curtis Swango, it turned out) denied his request for bond. Three months after the killing—two months after J. W.’s confession of the Till murder in Look—Kimbell was tried in the Sumner courthouse. Sheriff Strider leaned in for the defense and Attorney J. W. Kellum represented Kimbell. An all-white jury acquitted him after deliberating for four hours.

Coverage of the trial, what there was of it, referred back to Emmett Till. The Delta Democrat-Times pointed out that this time the victim was not some Chicago “smart alec” but a highly respected local black man, that there was no issue of white southern womanhood involved, that the NAACP stayed away—“No flashbulbs popping, no television cameras, no reporters from all over the world milling around”—no one could say that Mississippi was backed into a corner, there was nothing to be defensive about. Still, the Democrat-Times noted, “no matter how strong the evidence nor how flagrant is the apparent crime, a white man can not be convicted in Mississippi for killing a Negro.”

Emmett Till’s murder, Faulkner argued, gave the lie to America’s Cold War talk of freedom and justice.

David Halberstam agreed. The young reporter returned to the Delta and wrote “Tallahatchie County Acquits a Peckerwood.” Mississippi, he noted, was divided into “the good people” like the jurors, and the peckerwoods like Kimbell, troublemakers prone to violence and intent on “keeping the niggers in their place.” The good people saw themselves as above the peckerwoods, above murder and mayhem. But they were every bit as invested in protecting their white supremacist birthright. “I suspect,” Halberstam wrote, “that the jurors who may have had misgivings were thinking that they had to go on living in the county, and how could they explain any other verdict to the neighbors. . .” The logic of white supremacy meant that even against their better judgment, the good people must close ranks with the peckerwoods. As Halberstam also pointed out, the Melton story barely got reported.

Before Emmett Till’s story faded further from view, the South’s most famous writer, William Faulkner, weighed in. He had written a widely reprinted open letter from Rome two weeks after they found the body. Faulkner asked if the white race, a mere quarter of humanity, could continue to commit crimes against colored people and survive? Perhaps the Till case might “prove to us whether or not we deserve to survive.” Emmett Till’s murder, Faulkner argued, gave the lie to America’s Cold War talk of freedom and justice: “If we as Americans have reached that point in our desperate culture when we must murder children, no matter for what reason or what color, we don’t deserve to survive, and probably won’t.” Having raised this disturbing point, Faulkner pulled back, urging African Americans to go slow, to be patient, to not push white southerners too hard. Black and white shared a culture, so together, gradually, they might eradicate the absurdity of racism.

Faulkner returned to the Till case nine months later in the June 1956 issue of Harper’s Magazine. He marveled at the progress African Americans had made in the course of three centuries—from savages eating rotten elephant meat in African jungles to George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington (!). Commenting on William Bradford Huie’s article, Faulkner asked what were whites so afraid of:

If the facts as stated in the Look magazine account of the Till affair are correct, this is what ineradicably remains: two adults, armed, in the dark, kidnap a fourteen-year-old boy and take him away to frighten him. Instead of which, the fourteen-year-old boy not only refuses to be frightened, but, unarmed, alone, in the dark, so frightens the two armed adults that they must destroy him.

Faulkner simply accepted Huie’s take on the Till story, especially the absurd notion that a fourteen-year-old boy frightened two big armed men. What, he asked, had caused southerners to fall so far from the valor of their ancestors, what now made them so fearful as to believe that, “as soon as the Negro enters our house by the front door, he will propose marriage to our daughter and she will immediately accept him?”

For all of his hedging and misplaced faith in moderation, Faulkner was on to something. If Emmett Till did not scare Milam and Bryant, the idea of assertive black men certainly frightened the white South. It went deeper than the old sexual fears of black men, Faulkner argued, to include the idea of blacks seeking justice and competing successfully in all areas of society against whites. “Fear, not hatred, is what I’ve experienced from Southern people,” Faulkner told a radio interviewer. He was right, fear was as much a part of white supremacy as hatred. Racism merged them, entwined them in bad faith, because fear rationalized hatred. Hatred could not justify child murder, but fear could.

__________________________________

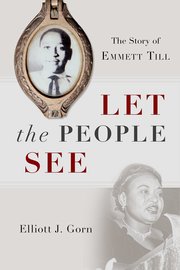

From Let the People See: The Story of Emmett Till by Elliott Gorn. Copyright © 2018 by Elliott Gorn and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

Elliott Gorn

Elliott J. Gorn is Joseph A. Gagliano Chair in American Urban History at Loyola University Chicago. He is author of several books, including Dillinger's Wild Ride: The Year that Made America's Public Enemy Number One.