How Amaranth Influenced Indigenous Culture and Cooking in the American Southwest

Michael Shaikh Explores the History and Legacy of Pueblo Cuisine in New Mexico

The first time I remember tasting amaranth was in Ray’s tortillas at the Indian Pueblo Kitchen in downtown Albuquerque in the summer of 2021. Ray was the executive chef then, and he had used a combination of amaranth and corn flour to make me a stack of floppy, round tortillas, each the size of a large sand dollar, to eat with a plate of bison ribs he had braised in juniper. Dusty and faintly golden, they were heavier than their size suggested and tore perfectly with just the right amount of resistance without leaving a frayed edge. When I bit into one, the tortilla momentarily hugged my teeth in a warm embrace before giving up its nutty, malty, and subtly sweet flavor.

Ray Naranjo is a Native American chef from Santa Clara Pueblo in northern New Mexico. He’s a big, affable man with a wide, warm smile, built more for a football field than his food truck, Manko. After leaving the Indian Pueblo Kitchen a few years ago, Ray opened Manko, a food truck and catering business serving a fusion of Native American cuisine—mostly from his Pueblo traditions—and New Mexican and Western food. A regular fixture of festivals and food events across the state, Manko is arguably New Mexico’s most beloved food truck. “When Ray was a boy, we didn’t have much money most days,” his mother, Marian Naranjo, a famous potter and Indigenous activist, told me. “Once in a while, the kids had to fend for themselves.

They were all responsible for the house and each other when I was working,” she recalled. Ray, she said, hated to clean, so he cooked. The second youngest of her four children, Ray was her most sensitive but also her most curious child. “Ray would just walk around Santa Clara, sometimes eating from trees, using old knowledge,” she told me at her home on the Santa Clara reservation outside Española, New Mexico. “Learning to eat well from the earth.”

At the heart of its culinary philosophy is the belief that people are within and part of their ecosystem, not separate from it.

Ray was around ten years old when he first thought of becoming a chef. “When I was a little kid, instead of going on a hunting trip with the elders, I stayed home and cooked Thanksgiving dinner. My mom was a hunter because we were part of the hunter clan, and when they came home, I had cooked a pretty big dinner. I am pretty sure I knew I wanted to be a chef then,” Ray told me. “I used to watch cooking shows on TV as a kid. There’s no way we could afford the ingredients on those shows. But I would kinda get creative with what we had back then and try to re-create versions of what I saw on TV, like stuffed burgers.”

Today, Ray is in his mid-forties and has been a professional chef for most of his adult life. After culinary school, like many other Indigenous chefs of his generation in the United States, Ray cooked in the kitchens of reservation casinos before focusing on his own Pueblo cuisine and working his way into the top job at the Indian Pueblo Kitchen at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque. Then, in May 2022, Ray set off on his own to start Manko. In Tewa, Ray’s ancestral language, manko means “come and eat.”

Ray’s home, Santa Clara Pueblo, sits in the shadow of Los Alamos, on the banks of the Rio Grande. In Tewa, Santa Clara Pueblo is called Kha’Po Owingeh (Singing Water Village). There are nineteen Pueblo tribes in New Mexico today; each is a sovereign nation on a federally recognized reservation with its own government. The Pueblo tribes share a common history, as well as aspects of culture, but remain diverse peoples, speaking several different languages and dialects. Hundreds of years ago, the Pueblo homeland reached from its heartland in New Mexico into Colorado and Arizona, but today, most Pueblo reservations are located, like Santa Clara, along the upper reaches of the Rio Grande in New Mexico.

Over the past few years, Ray has patiently introduced me to Pueblo cuisine. Traditional, pre-European Pueblo food follows the seasons and is deeply rooted in the land of the nineteen nations. At the heart of its culinary philosophy is the belief that people are within and part of their ecosystem, not separate from it. Pueblo cooks use corn, beans, and squash, as well as wild onions, mushrooms, purslane, and juniper. Piñon nuts and pumpkin seeds add texture to dishes. Bison, elk, deer, fish, and regional birds are important animals. Honey and berries like currants, chokeberries, and blueberries add sweetness. Dishes are flavored with epazote, sage, mint, cota, and wild parsley and seasoned with native chilies and, most important, salt that the Pueblo people traditionally harvested from the Zuni Salt Lake and the Estancia Valley, both in New Mexico.

Wheat, dairy, beef, pork, chicken, and spices like black pepper are not part of heritage Pueblo cooking, as most of these were introduced by Europeans. But Ray, like other Pueblo chefs, often incorporates them into his contemporary fusion cooking. Ray also cooks with amaranth, another ancient precolonial ingredient often used in Pueblo cuisine. In one form or another, amaranth is usually on the menu at Manko, as in the Native Berries and Bird Seed Salad—a colorful and gratifying bowl of spinach tossed with quinoa, heirloom tomatoes, feta, and sunflower and pumpkin seeds, dressed in vinaigrette made with local berries, and then topped with popped amaranth to add a malty crunch.

*

Amaranth is sometimes referred to as the Fourth Sister to the sacred Three Sisters—corn, beans, and squash—which are at the heart of not only Pueblo cuisine but also the cooking of many Native American nations. In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer, a botanist and a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, talks about the grammar of animacy among Indigenous languages to address the nonhuman living world, like plants and animals, as well as objects, places, and landscapes imbued with sacred meaning: “Imagine seeing your grandmother standing at the stove in her apron, then saying of her, ‘Look, it’s making soup. It has gray hair.’” She points out that in English, we never refer to anyone, especially not a family member, as “it.” That would, of course, be deeply disrespectful. “It robs a person of selfhood and kinship, reducing a person to a mere thing.” In most Indigenous languages, she says, “we use the same words to address the living world as we use for our family. Because they are our family.”

Amaranth is not my family in that sense. But I have spent so much time with her, and with people for whom she is family, that I can’t help but show her that same grammatical respect. She has many varieties, but I am most familiar with Amaranthus cruentus (red amaranth). She is an endearingly beautiful plant with a tall, slender, but sturdy red stem decorated with wide, flat, fluttering mint-green leaves that taper toward the top, giving way to bundles of soft, finger-like flowers the color of plums or an old brick path soaked by rain. These flowers always seem to lean in your direction, seeking your attention, wanting to gently stroke your head as you walk by.

The human relationship with amaranth is ancient. Grown all over the world but native to the Americas, amaranth was first cultivated by the Olmec and the Maya some eight thousand years ago, not only because of the plant’s beautiful plumes but also because of what they contained within. Each of her bright, floppy crimson fingers contains thousands of highly nutritious pinhead-sized seeds. Her nutrient-dense, peppery leaves can be eaten like spinach. Friends with roots in Tamil Nadu in South India often make pooriyal, a stir-fry of fresh amaranth leaves, chilies, and coconut. Gardeners adore amaranth for her ornamental flowers, which remain bright long after they’re dried. The plant’s name is derived from a Greek word meaning “unfading” or “immortal.”

Health food enthusiasts proclaim her yet another “superfood,” and as they did avocados, quinoa, and goji berries, they have turned amaranth into a billion-dollar industry. Climate activists also evangelize the plant as a food for the future because she resists drought, grows fast, and tolerates tough soils. In fact, amaranth is right at home in a high New Mexico desert, in a crack in a New York City sidewalk, or even in space, where NASA grew some in the 1980s. Big Ag fears varieties of amaranth as an existential threat to industrial crops, since the plants are unperturbed by the industry’s arsenal of weed killers.

The heroic persistence of the Pueblo people to remain, now and forever, in their world proves beyond all doubt that saving a food culture is the same thing as saving lives.

Like her relative quinoa, amaranth is technically a pseudocereal and is naturally gluten-free. The seeds contain all nine essential amino acids, making amaranth among the most protein-dense edible plants on earth. The seeds are also rich in lysine, an amino acid lacking in corn. So when Ray toasts and grinds amaranth seeds into a flour, or masa, and mixes it with a corn masa, the result is not only a delicious tortilla but also a far more nutritionally balanced food.

Braised bison with amaranth tortillas is a dish Ray is particularly proud of—one that displays the diversity of Native cuisines in North America: bison meat, a staple of Great Plains nations like the Arapaho, Crow, and Sioux; juniper, a common ingredient in Pueblo and Diné (Navajo) cooking; and amaranth and corn tortillas, a tradition dating back thousands of years to the ancient Maya. The Ancestral Puebloans, Ray’s ancestors, who lived across the northern Southwest until the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century, also had a tradition of eating amaranth and corn tortillas. The Ancestral Puebloans had grown corn for thousands of years, but amaranth is a relatively recent addition to Pueblo food, something they started growing only about eight hundred years ago.

Like corn, amaranth was venerated in Indigenous societies in the Americas before the European invasions. Colonial Spanish Catholics outlawed amaranth five hundred years ago across their “New World” colonies. Believing it was sacrilegious, they attempted to decimate it throughout the Americas with a myopic crusading zeal akin to today’s drug war to eradicate the coca leaf. “Amaranth was embedded deeply into our ancestral culture. It was an important part of our cuisine that also connected us to our Creator. But the Spanish took it from us, and then the United States came and changed things even more,” Ray explained during one of our first conversations, referring to the back-to-back colonialisms the Pueblo people have endured since the late 1500s. “It’s only really in the past few years that we’ve been able to really bring amaranth back now,” he said, with a sense of pride.

The Pueblo people point out that New Mexico is the oldest colony in what is today the United States. Since the late fifteenth century, their nations, as well as other Indigenous nations, have had their land occupied almost continuously, first by Spain, then briefly by Mexico, and finally by the United States. Although the Pueblos’ experience with each colonial power was distinct, the common element is that they all intentionally divided Indigenous people not just from one another but also from their cultures.

Much like the people who first grew amaranth on the continent, the plant itself endured centuries of violence and erasure. Perhaps what’s most important about this story is that the heroic persistence of the Pueblo people to remain, now and forever, in their world proves beyond all doubt that saving a food culture is the same thing as saving lives.

__________________________________

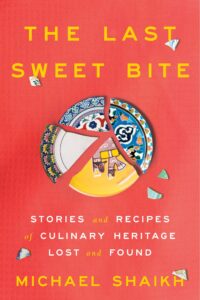

From The Last Sweet Bite: Stories and Recipes of Culinary Heritage Lost and Found by Michael Shaikh. Copyright © 2025. Available from Crown, an imprint of Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Michael Shaikh

Michael Shaikh is a writer and human rights investigator who has worked for twenty years in areas marred by political crisis and armed conflict. He has worked at Human Rights Watch, International Crisis Group, the Center for Civilians in Conflict, the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and the New York City Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice. Michael is on the board of Adi Magazine. Originally from Cleveland, Ohio, he lives in New York City.