How Alice B. Toklas Found her Voice Through Food

On Writing Her Own Cookbook, After Gertrude Stein

In many ways, Alice B. Toklas had been preparing to write a cookbook all her life. “Cook-books have always intrigued and seduced me,” she would later admit; “when I was still a dilettante in the kitchen they held my attention, even the dull ones, from cover to cover, the way crime and murder stories did Gertrude Stein.” Although she had grown up in a home where servants did all the cooking, she had taken a gentlewoman’s interest in knowing how to cook, what to serve, and the right way to serve it. Her acquaintance with French food, meanwhile, was long-standing, for despite the Toklas family’s German-Jewish roots, their cooks in San Francisco had always cooked French food for them. Still, as she later put it, “before coming to Paris I was interested in food but not in doing any cooking.”

Only by living in France had she slowly become aware of the many fine (and different) cooking traditions that existed within that country—not only of haute cuisine and cuisine bourgeoise, but also the incredibly varied regional cuisines: Norman, Alsatian, Burgundian, and Provençal dishes would all find their way into her cooking repertoire. Her exposure to the various forms of French cooking was broadened as well by her social mobility: throughout the first half of the twentieth century Toklas dined in the finest restaurants and grandest private homes, but she also ate in the most humble restaurants and artists’ studios. Like A. J. Liebling, she knew and enjoyed the cooking of both the rich and the not-so-rich.

Cooking had ultimately become an important aspect of her life with Gertrude Stein: Stein, in fact, had first encouraged Toklas to express her creativity in the kitchen. Toklas’s first dishes for Stein consisted of “the simple dishes I had eaten in the homes of the San Joaquin Valley in California—fricasseed chicken, corn bread, apple and lemon pie.” Such modest attempts—undertaken primarily to soothe homesickness—would broaden and escalate over the coming years, with Toklas collecting French recipes of historical, cultural, regional, or personal significance and then re-creating them as special treats for Stein and for their friends. She had also learned a good deal about cuisine bourgeoise by watching their various housekeepers, particularly their first, Hélène, who was tremendously gifted in the kitchen (but who felt very strongly that Toklas herself ought not to cook, for cooking was the job of a servant). Finally, of course, there was the cooking Toklas had done at the château they rented for so many years at Bilignin, which after all was a mere 50 miles southeast of Bourgen-Bresse, capital of the Ain department, in a region justly famous for its chickens and for its farm produce, and “recommended by the Guide Gastronomique . . . [for its fine] market and provision shops.” Toklas’s hands-on, garden-to-table cooking at the château, supplemented by these fine local ingredients, ultimately endowed her with an acute awareness of the importance of terroir.

Even though Toklas did not cook daily in Paris—that work fell to their various housekeepers, so long as they had one—she did enjoy cooking for special occasions, as when she decorated a cold poached sea bass, quite colorfully, for Picasso: “I covered the fish with an ordinary mayonnaise and, using a pastry tube, decorated it with a red mayonnaise . . . [and then made] a design with sieved hard-boiled eggs, the whites and the yolks apart, with truffles and with finely chopped fines herbes. I was proud of my chef d’oeuvre . . . and Picasso exclaimed at its beauty. But, said he, should it not rather have been made in honor of Matisse than of me.” (He was right, of course: the fish had been decorated in bright colors more characteristic of Matisse.) Toklas had also been known to step in and help friends in the kitchen, as in the comedic set piece in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, when Picasso and his mistress Fernande are on the verge of a dinner party crisis, and Toklas saves the day by taking Fernande out shopping, then cooking up Fernande’s riz à la Valencienne (better known by its Spanish name, paella valenciana) in the apartment of Max Jacob. More often, however, Toklas simply became excited about a particular ingredient—such as wild strawberries, or the beautiful baby vegetables from the Bilignin garden—and selected a radically simple preparation that showed off that exquisite item to best advantage.

“Toklas found herself coming back, as ever, to the realization that all of her cooking was intimately related to Stein.”

As she sifted through a lifetime’s worth of recipes, Toklas found herself coming back, as ever, to the realization that all of her cooking was intimately related to Stein. It was Stein, after all, who had been at the center of every meal and gathering, who had supported and encouraged all her efforts in the kitchen, and who had provided Toklas with a new cookbook to read and enjoy each Christmas. Even during the darkest winter of World War II, while the two were holed up in Culoz, Stein had somehow managed to arrange that “the 1,479 pages of Montagné’s and Salles’s The Great Book of the Kitchen passed across the [enemy] line[s] with more intelligence than is usually credited to inanimate objects.” Toklas had adored that hefty and extravagant Christmas present, observing that “though there was not one ingredient obtainable it was abundantly satisfying to pore over its pages, imagination being as lively as it is.” During that same hungry year, Stein and Toklas discussed collaborating on a cooking-related project—for Lucien Tendret, the nephew of Brillat-Savarin and author of the brilliant and fantastical cookbook La Table au Pays de Brillat-Savarin, was the grandfather of their Culoz landlady. (The much-loved book had in fact been written in Culoz after Tendret had retired from his law practice in Belley.) Upon signing the lease for their Culoz house, Stein and Toklas were presented “a copy of this delectable book” by Tendret’s grandson, and they immediately recognized the genius of its writing. One of the most erudite (as well as amusing) French cookbooks, La Table au Pays features recipes that begin with epigraphs from Plato, and a preface that can only be described as a tour de force of gastronomic historiography. (Richard Olney would write about it frequently, and adapt several of its very complicated recipes for the home cook; Julia Child, meanwhile, owned a first edition.)

“Since the 1933 publication of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Toklas’s voice actually seemed to belong more to Stein than to herself, for Stein had captured it so brilliantly in that fine and amusing bestseller.”

La Table au Pays was all the more precious to Toklas and Stein because it described fine foods and food preparations specific to their little subregion of the Ain, known as the Bugey. The idea of translating the book into English became even more exciting when they discovered another, related text: the Tendret family recipe book—a book of everyday dishes that were entirely different from those fantastically complicated preparations Tendret had so lovingly described in La Table au Pays. These were instead the simple dishes that Tendret and his family had regularly been served by their skilled family cook. In the end, however, Stein and Toklas had abandoned the project because, as Toklas later noted, “the recipes [of La Table au Pays were] exciting to read but are not useful even today [when the war is over]. Take for instance Lobster, Breast of Chicken and Black Truffle Salad”—a salade composée requiring not only lobster, capon, and truffles but also endive, ham, and turkey.

As she prepared to write her own cookbook, Toklas was grappling with another, more fundamental problem: her identity as a writer. Throughout their life together, Stein had been the writer, and Toklas had no desire now to usurp her deceased partner in that role. Moreover, there was the question of confidence: Toklas had not published anything since she was seventeen, when she had “sold a joke for five dollars to Life.” And, in truth, since the 1933 publication of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Toklas’s voice actually seemed to belong more to Stein than to herself, for Stein had captured it so brilliantly in that fine and amusing bestseller.

The question, then, of how she might now establish her own voice (or, looked at another way, how Toklas might now live up to Stein’s earlier evocation of it) was daunting. Particularly since, as Stein had once noted (in Toklas’s voice), Toklas found writing so difficult: “I am a pretty good housekeeper and a pretty good gardener and a pretty good needlewoman and a pretty good secretary and a pretty good editor and a pretty good vet for dogs and I have to do them all at once and I found it difficult to add being a pretty good author,” The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas had ended. “About six weeks ago Gertrude Stein said, It does not look to me as if you were ever going to write that autobiography. You know what I am going to do. I am going to write it for you . . . and she has and this is it.”

Given such a precedent, could Toklas come up with an equally brilliant narrative strategy, one that could respond to Stein with the same playfulness that Stein had once responded to Toklas—and with an equal (and equally tacit) testimony that, above all else, the two were one?

Was it possible, in other words, for this cookbook to be more than a cookbook?

__________________________________

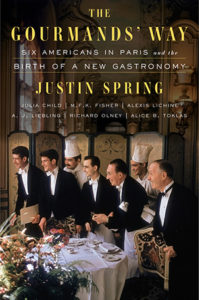

From The Gourmands’ Way: Six Americans in Paris and the Birth of a New Gastronomy. Used with permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2017 by Justin Spring.

Justin Spring

Justin Spring is a writer specializing in twentieth-century American art and culture, and the author of many monographs, catalogs, museum publications, and books, including the biographies Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Steward, Professor, Tattoo Artist, and Sexual Renegade, a finalist for the National Book Award, and Fairfield Porter: A Life in Art.