Thinking he would grow up to be “a veterinarian with a flashy station wagon & a flashy blonde wife, raising German Shepherds in some fancy suburb,” Sam Shepard entered his senior year at Duarte High School already knowing there was no reason for him to apply himself to his studies now—as he had never done before—so he could leave Duarte to go off to college.

Although his plan at the time was eventually to apply to the University of California at Davis, Shepard already knew he would be spending the next two years at Mount San Antonio College, the local junior college known as Mt. Sac, less than a half hour by car from his house.

Nonetheless, in what can only be described as a truly inspired bit of fantasy, Shepard later wrote an autobiographical sketch that appeared in the American Place Theatre newsletter in April 1971. In it, according to biographer John J. Winters, Shepard claimed that during this period of his life in Duarte, he stole cars, drove recklessly, and was thrown in jail for flipping off the wife of the police chief in Big Bear Lake, a resort town in the San Bernardino Mountains.

During the course of an extensive interview 26 years later in The Paris Review, Shepard further embellished his past by saying, “My history with booze goes back to high school. Back then there was a lot of Benzedrine around, and since we lived near the Mexican border I’d just run over, get a bag of bennies and drink ripple [sic] wine. Speed and booze together make you quite … omnipotent. You don’t feel any pain. I was actually in several car wrecks that I don’t understand how I survived.”

In actual fact, Duarte is about 150 miles and a three-hour drive from the Mexican border. But then, as Sandy Rogers says, “I don’t think Sam was ever a wild boy, but I remember one time he did bring home this big sawhorse with lights on it that flashed on and off, from a construction site, and put it in his room. He had absolutely stolen it, and Mom said, ‘You better take that back.’ He put it under his bed, but the lights just kept right on flashing on and off. And I’m really not aware of anything else he ever did like that.”

Shepard’s only other known act of rebellion during his senior year at Duarte High School was showing up late for a graduation rehearsal. “He had been late, and so they did not let him walk,” Sandy Rogers says. “We do have a picture of him in his cap and gown, but it was not taken at graduation.”

Shepard also wrote that his father would “probably shatter my dreams immediately.”During this period of Shepard’s life in Duarte, his father, now 44 years old, was the one who began acting out in a way no one in the family could have ignored. Precisely what triggered this behavior is impossible to say, but Sam Rogers’s deep-seated dissatisfaction with his life had already been building for years.

“My dad was an alpha male, definitely,” Sandy Rogers says. “And it was not just that people who weren’t as smart and talented as him were richer and seemed happier but the fact that he had done all the right things—coming out west and getting himself a college degree and a good teaching job—but those jobs didn’t pay shit. Just because he was teaching at San Marino High School in a rich neighborhood didn’t mean anything. He was making the same as anyone teaching at any high school. And so we never had a lot of money, but we were okay.

“What also really pissed my dad off was that even though he was the head of the language department there, he still had to do what he was told by his boss, the principal, whose name was actually ‘Mr. Dingus.’ I remember when my dad had given this kid an F and the kid couldn’t graduate because of that, and my dad said, ‘Well, he deserved less than an F,’ but the principal let him graduate anyway, and that kind of thing happened over and over again. My dad was a tough guy and a disciplinarian, and he didn’t like people stepping across his boundaries, and so all this was always very frustrating for him.”

Although Rogers was displeased with his position in the chain of command at San Marino High School, the graduating class of 1960 thought so highly of his teaching abilities that they dedicated their yearbook to him. A year later, he was awarded a Fulbright Linguistic Scholarship, which enabled him to spend the summer of 1961 studying Spanish in Bogotá, Colombia.

In a letter Shepard wrote to his grandmother after spending that summer working as a veterinarian’s assistant in West Covina, he brought up the possibility of not going to college at all but rather heading off to the Yukon to work in a lumberyard. Noting that Sam Rogers was due to return home from Colombia on Saturday, Shepard also wrote that his father would “probably shatter my dreams immediately.”

According to Shepard biographer John J. Winters, over the course of the three months Rogers spent in Bogotá, he may have fallen in love with the daughter of his host family. In Winters’s words, “There are some who say Sam Rogers left his heart in Colombia and was never the same after returning home.”

*

Known in Hindu culture as “the tree of God,” the deodar cedar has survived in the Himalayas for as long as a thousand years. Those in the dense grove across the street from the Rogers house on Lemon Avenue in Duarte were far more short-lived. And so when Sam Rogers came home from work one day to see all those majestic trees gone, his immediate reaction was more than just shock and surprise.

“They had all been cut down by the city, and it might have been because of some kind of tree disease,” Sandy Rogers says, “but my father didn’t know anything about it beforehand, and so he completely blew it. Because the neighbor across the street was on the city council, the first thing my father did was go over there and scream at those people, who of course were also friends of ours. There had been incidents before when he had been drinking, but this was different. He was devastated because there had been a forest there and now it was gone and the whole place had been completely changed. And I don’t think he ever recovered from that. For him, this was the turning point. It just really sent him over the edge.”

Whether or not the destruction of the deodars finally convinced Sam Rogers that he could no longer control his life as he had while piloting his B-24 bomber in World War II, and so he then decided there was no longer any reason for him even to continue trying, no one can say for sure. But from this point on, he did begin acting like an out-of-control alcoholic, thereby making everything just that much more difficult for him and his family. In a relatively short space of time, Rogers crashed his car into a tree.

He began going off on extended binges during which he would stay in a local motel, often with a woman he had met that night while drinking in a bar. He would then return home just long enough to dump his dirty laundry on the kitchen table along with a note instructing his wife not to starch his shirts.

How he was still able to show up to teach at San Marino High School five days a week can only be explained as the kind of behavior high-functioning alcoholics can sometimes maintain for long periods of time As Shepard described it, the final confrontation between him and his father in Duarte took on the air of Greek tragedy. During an interview with Terry Gross on National Public Radio’s Fresh Air in 1998, Shepard called the incident “a holocaust” in which “the old man” literally “destroyed the house … Broke windows, tore the doors off, stuff like that.”

According to biographer John J. Winters, Shepard wrote another account of the incident in a notebook entry dated May 20, 2008. In it, he stated that his father had smashed windows in the house, torn the front door off its hinges, and then set the backyard on fire. In his Paris Review interview in 1997, Shepard referred to his father as “a maniac, but in a very quiet way. I had a falling-out with him at a relatively young age by the standards of that era. We were always butting up against each other, never seeing eye-to-eye on anything, and as I got older it escalated into a really bad, violent situation. Eventually I just decided to get out.”

By far the single most personal statement Shepard ever made about how deeply his father’s drunken behavior affected him can be found in a story titled “Orange Grove in My Past,” from Day out of Days. In it, he writes:

I thought I had done my level best, done everything I possibly could, not to become my father. Gone out of my way in every department: changed my name, first and last, falsified my birth certificate, deliberately walked and swung my arms in exact counterpoint to the way he had; picked out clothing the opposite of what he would have worn, right down to the underwear; spoke without any trace of a Midwestern twang, never kicked a dog in the ribs; never lost my temper over inanimate objects, never again listened to Bing Crosby after Christmas of 1959, and never ever hit a woman in the face. I thought I had come a long way in reshaping my total person. I had absolutely no idea who I was but I knew for sure I wasn’t him.

“As far as I know,” Sandy Rogers says, “my dad never laid a hand on my mom. As far as I know. I swear. I never saw him touch her. In my life, he never touched her. But just like there were so many things I did not tell my brother, there was stuff that happened to Sam he never told me about or that I didn’t see. I mean, I can guess, but I don’t know. Because I cannot know.

“Now, I was there the night when my mother locked my dad out of the house, but there was no physical violence. Well, yes, there was physical violence, because my dad took a crowbar to the door. And then Sam came out of his room and said, ‘Dad!’ And then my dad turned around, and my mom began screaming, but nothing came of it except for the broken door. And my dad never set the yard on fire. Sam’s writing makes it all sound better than it really was from my point of view, but I was there when it happened.”

In the same letter to his grandmother in Illinois expressing his fears about what would happen when his father came back home from Colombia, Shepard also wrote that he intended to major in education at Mount San Antonio College. Having already signed up for the golf team, he was also thinking about trying out for track as a high jumper.

There were times when I would be with Sam, and he would say, “It’s the old man.”As he began the first of his three semesters at a school best known for its agricultural program, Shepard abandoned these plans and joined the drama club instead. He then appeared in four plays. By far, his most notable performance was as Elwood P. Dowd, the central character in Harvey, a genial fantasy written by Mary Chase that had already been made into a popular movie starring James Stewart, who was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance. A perpetually pixilated eccentric who liked to hang out in bars but who did not resemble Sam Rogers in any way whatsoever when he was drinking, Dowd is accompanied throughout the play by his best friend, a six-foot, three-inch rabbit named Harvey whom only Dowd can see.

“I saw Sam in Harvey at Mt. Sac, and he was amazing,” Sandy Rogers says. “He was just great and I think he also did some writing while he was there. Then he linked up with the Bishop’s [Company Repertory] Players at the Pasadena Playhouse and worked with them there for a little while.”

During his freshman year at Mt. Sac, Shepard also wrote his first play. Discovered in the college archives by biographer John J. Winters with the help of a current faculty member, The Mildew, a one-act comedy, occupied ten pages in the school’s 1961 student literary journal. Although the play was never performed, Winters wrote that “for a community college freshman it shows a remarkable eagerness to experiment and a transgressive sense of humor.”

But, as he also noted, “Shepard’s first play lacks a traditional ending.” Whatever The Mildew’s merits and faults may have been, Shepard still thought of himself as an actor rather than a writer and it was this self-characterization that enabled him to finally leave Duarte for good. After dropping out of Mt. Sac in the spring of 1963, Shepard worked on a horse farm in Chino, California. He then delivered newspapers from his red-and-white Chevrolet in Pasadena. It was while doing so that he saw a classified ad in the newspaper for the Bishop’s Company Repertory Players, which was looking for actors, and decided to audition for a place in the troupe.

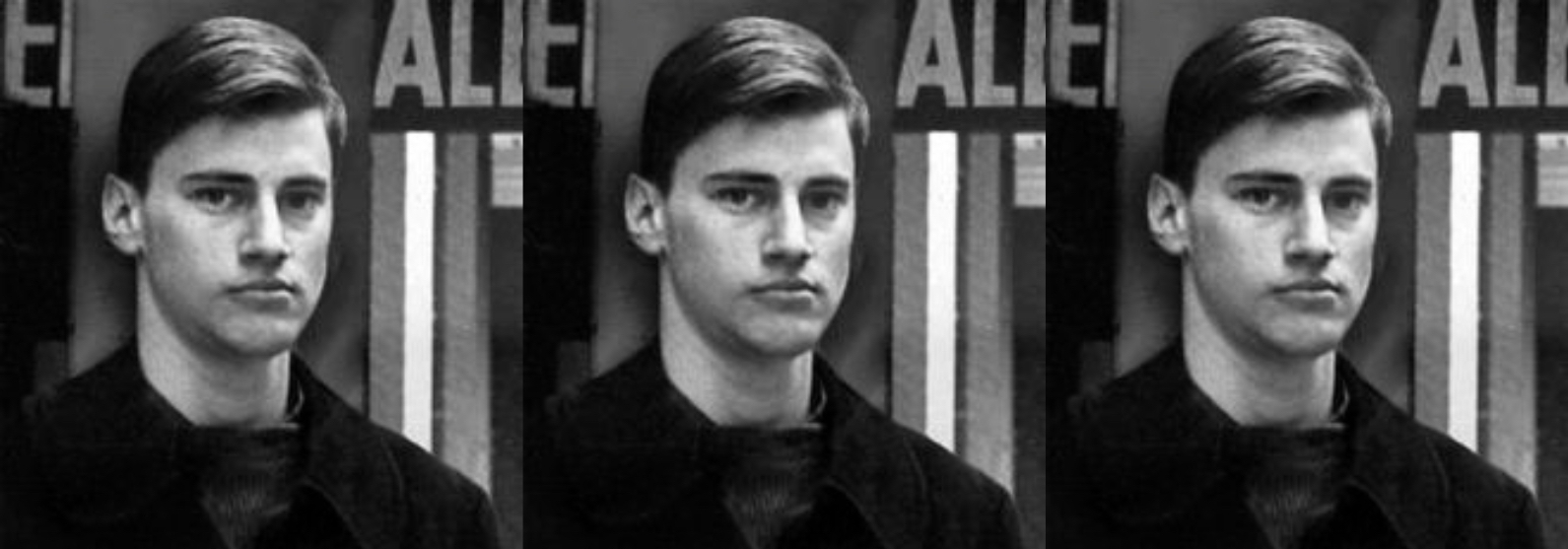

In what has become yet another integral part of his legend, Shepard was handed a book of Shakespeare’s plays at the audition but was so nervous—and so completely untrained as an actor—that he read not only his assigned dialogue but also the stage directions accompanying it. Young, eager, and good-looking, he was nonetheless hired for the princely sum of ten dollars a week to join the Bishop’s Company on its cross-country tour, which eventually brought him to New York City.

By then, Sam Rogers was no longer even living in the house on Lemon Avenue. “He kind of left and came back a couple times,” Sandy Rogers says. “And then my dad was around the area, but we didn’t know where. I remember driving with my mother one day, and there he was, walking down the street, and I went, ‘Mom, stop! I want to see Dad.’ So, my mother stopped and he was all pissed off, because he thought she had been out looking for him.”

After being married for 25 years, Sam and Jane Rogers divorced in 1968. By then, Rogers had already begun spending time with a woman who played piano in one of the local cocktail bars where he was a regular. Eventually, the two got married and moved to Altadena, but the marriage lasted for only a few years. Despite having worked at San Marino High School for 17 years, Sam Rogers was fired from his position as a teacher and the head of the language department in 1969.

“I really don’t know why or even when he got fired from his teaching job,” Sandy Rogers says, “but I do know he dropped his thermos in the teacher’s lounge one day, and there was whisky in the coffee. And he had been showing up drunk and teaching drunk. And then he took off. There were times when I would be with Sam, and he would say, ‘It’s the old man.’ Meaning that what he [Sam] was doing was because of [our father]. I will tell you this: Sam was haunted by my dad. He was definitely haunted by him.”

__________________________________

From True West. Reprinted by arrangement with Crown, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2023 by Robert Greenfield.