How a Small French Newspaper Began the Tour de France

Adin Dobkin on L'Auto, the War Torn Year of 1919, and the Beginning of the Legendary Bike Ride

Henri Desgrange watched the celebrations pass by on rue du Faubourg Montmartre. Crowds renewed themselves along the blister of a road through Paris’s ninth arrondissement, on the Seine’s right bank. The editor stood, stiff. His soldier’s posture had not yet left him. When he’d held his unit’s colors, his face set for the army photographer, it had taken effort to stay as rigid as his soldiers, three decades younger than Desgrange. Anyone who knew him would say he thought nothing of the gap in their ages.

Stasis didn’t suit him. Desgrange always appeared in constant motion: his white hair swept back over his still dark, wayward brows, his chin cocked out, his eagle nose just barely upturned, as if to focus on some prey. He had watched his neighborhood dim in the preceding years, though that day it was, for at least a moment, reborn. The powder-blue dressing rooms and gilt mansions of les Grands Boulevards, their extravagant rose gardens concealed behind modest steel fences, all remained a short walk away, but the artists who had once made their homes nearby had moved to the city’s left bank and carried Paris’s cultural mass with them.

The occasional salon and cabaret still opened its doors on fall evenings like this one, however, and new jazz clubs had moved into the shuttered spaces between, buoyed by the unending tide of the city. Desgrange, the editor-in-chief of the sports daily l’Auto, could look out his office window and see the corridor that led to Bouillon Chartier’s entrance where waiters scribbled out customers’ receipts on unfussy paper tablecloths. He’d sometimes take his journalists to the restaurant after editorial meetings, when a walk to boulevard Montmartre felt too far with the evening’s deadlines. If he turned his head to the left, he could just make out the second-story awning of Gaumontcolor. The cinema’s neon lights cast a faint glow on the opposite wall; geometric shapes snapped in and out of existence on the pavement underfoot.

Anyone waiting outside the theater that day was subsumed by the passing bodies who crowded the Faubourg Montmartre street. Few were willing to miss the celebrations that continued into the late afternoon. For the first time in years, the streetlights remained lit as the evening aged but did not wane; they cast a glow on the people’s newly freed movements well into the night.

Parisians, Americans, British, Belgians—most anyone who found themselves in the French capital—amassed on the streets that day to celebrate the armistice signed between the Allied countries and Germany. They arrived knowing the fighting on the western front had ended at 11:00 am, though most who crowded onto the avenues had not yet heard what the document’s terms were. Whatever clauses and subclauses had been agreed on by their leaders and those on the table’s opposite side mattered little to the people’s immediate celebrations: it was enough that the thing was through.

No matter the conditions of the armistice, no matter how much Germany paid for those four years, the document couldn’t make up for the war’s cost.

No matter the conditions of the armistice, no matter how much Germany paid for those four years, the document couldn’t make up for the war’s cost. Like the rest of France, Desgrange had been consumed with the war. It had stamped his existence, left no corner un-inked. And his country? The war had threatened to tear it from its foundation, to cart off its remains, to expand Germany’s excision of territories and to break apart the alliance France had formed with Great Britain.

he country’s borders had not collapsed any further in the war—they’d expanded—but the conflict had succeeded in its first aim: to uproot the ground in tracts of land to Paris’s northeast. In doing so it shattered those young men, and plenty of old ones, too. Men who had been sent away in those first days of fighting with spirit in excess. Their stamina hadn’t lasted as long as the war did. Those men couldn’t be blamed; they had volunteered for a tragedy few had expected or prepared for, even those who led the aggressors.

A few saw how war had changed in the 60 years before 1914, in the cast artillery guns and industrial train tracks that ran like roots behind units in the Crimean War and in Vicksburg’s trench networks in the American Civil War. The Great War revealed those logistical and engineering lessons as ruinous, if inevitable, advances to warfare. Little could have protected the men on the front, short of killing every last German who had stepped onto their country’s trampled ground. Underfoot, the land carried each side. It held as they advanced and retreated, back and forth, but after four years it was broken: its roads dredged up and its farmlands and forests fallow. Negotiating with German generals and politicians might have spared lives, but after the war had slowed, burrowed into the clay, no conversation could have brought back those poilus Desgrange had funneled through l’Auto’s offices.

Desgrange paused. His fingers hovered over the keys. The paper’s founding message, written by him and published in l’Auto’s first issue on October 16, 1900—19 years ago—said the newspaper would avoid political issues, in contrast to its many competing sports dailies. He and l’Auto’s advertisers had seen an opportunity to differentiate themselves from Le Vélo, their widest-circulating opponent, whose writers and editors regularly waded into domestic political conversations. Le Vélo’s editor-in-chief, Pierre Giffard, had come to the defense of Alfred Dreyfus in its pages, to the chagrin of Le Vélo’s conservative advertisers. Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army, had been convicted of selling military secrets to the Germans.

At the time of Giffard’s defense, those who supported Dreyfus hoped to reopen his case and overturn the conviction, while anti-Dreyfusards thought that doing so would weaken people’s faith in France and its government. An antisemitic undercurrent ran throughout. At the time of the affair, Desgrange was a public relations representative of Clément-Bayard automobiles, itself a Le Vélo advertiser. He had already left his days as a professional cyclist behind. He had not broken from the sport entirely, though.

Only a few years before he had become the director of Parc des Princes, an arena with a cycling track in the city’s western suburb of Boulogne-sur-Seine. Desgrange wrote articles and opinion pieces about physical education and sports for Le Vélo and other publications outside his regular public relations duties. As the Dreyfus Affair continued, he remained publicly mute, a quality that appealed to his employer, Adolphe Clément-Bayard.Soon after Giffard declared his support of Dreyfus in his newspaper’s green-tinted pages, Clément-Bayard, the founder of the company bearing his name, brought Desgrange into discussions between Le Vélo’s advertisers. Clément, like the other corporations who advertised in the paper, had publicly disagreed with Giffard’s slant in Le Vélo’s coverage. Clément and the others had pulled their advertisements in protest. They had little desire to return that money to Le Vélo anytime soon.

Instead, they hoped to create a competing sports daily that would sate the public’s interest in athletics without the political coverage that had fragmented readership. Clément believed Desgrange could be an ideal editor for the new paper: he was a cyclist who had achieved some public acclaim after setting records in the hour, the 50 and 100 kilometers, and the 100-mile lengths on bicycles. He had written columns and books on his own experiences. As a public relations manager, he knew how to deal with journalists, even if he wasn’t one himself. The advertisers didn’t want to consider anyone else for the job; they offered the editor-in-chief position to Desgrange. He accepted.

They hoped to create a competing sports daily that would sate the public’s interest in athletics without the political coverage that had fragmented readership.

L’Auto’s founding message well represented its early stance toward politics, even before the war broke out. “What we wanted to say is said,” Henri wrote to l’Auto’s readers of the Dreyfus Affair, though the paper had said nothing until that point. He didn’t comment on Dreyfus again. The advertisers of the new sports daily, yellow tinted in contrast with Le Vélo’s green, were satisfied with their investment.

L’Auto’s founding and the Dreyfus Affair were far from Desgrange’s mind that November evening. His enemies, those his readers and advertisers shared, weren’t fellow Frenchmen but foreigners. He saw little chance a civil war would erupt between his fellow citizens who hated the Germans and those who thought they were being treated too harshly in their defeat. The few who believed that were in the minority and most were smart enough to recognize it and watch their own language. Le Vélo had shuttered in 1904 and the war had created a common enemy, one all of Paris could agree upon—Desgrange was free to write as he pleased.

Given the celebrations on most every Paris street, in countless small towns on the city’s outskirts, and in trenches that had been rendered worthless, l’Auto’s major advertisers like Jacques Braunstein at Zig-Zag and the Palmer Tire executives wouldn’t mind their ads abutting another of Desgrange’s political columns. They had remained loyal to the editor over the years. They had trusted him to expand the newspaper’s circulation in its first years as it competed directly with Le Vélo, and had stuck by him once Le Vélo had closed, quotas on materials had restricted l’Auto’s coverage, and its reporters—fighting-age men—had been called to the front. The newspaper’s readers had more pressing concerns than what l’Auto covered, cycling and gymnastics, running and yachting. But the sporting events Desgrange and his correspondents wrote about, those that continued in the wartime years, provided those readers with a release from the events that filled the pages of other newspapers: the movements of battleships, the arrest of foreign spies not far from where they lived, the deployment of units filled with sons, husbands, and fathers.

In l’Auto’s early days, Desgrange worked to live up to his advertisers’ initial confidence. His public relations experience, however, hadn’t carried him far in the newsroom. He had few ideas for stories and didn’t have much knowledge on how to manage a team of journalists. He only followed what others in the industry did and hoped the absence of something—political coverage—would be enough to drive readers to l’Auto. His brash writing hid a caution in business manners: whenever possible, he preferred others take risks in developing new projects while he waited to see whether their ventures would pay off. Given that plenty of other sports dailies were still in the market, even after Le Vélo faltered, l’Auto’s circulation stalled in those first years. The newspaper’s future had been uncertain enough that Desgrange’s job had been threatened. The advertisers expressed their hope he would turn things around, a sign that anyone without his relationships would have already been fired from the job. The threat wasn’t enough to change Desgrange’s nature, but it at least opened him to others’ ideas.

Desgrange held an editorial meeting in response. He asked the journalists who worked under him and those administrators on the business side of the paper for their ideas on how l’Auto could grow its subscription base. Géo Lefèvre, a 26-year-old cycling and rugby correspondent whom Desgrange had hired away from Le Vélo, spoke up. Lefèvre’s previous employer had sponsored sporting competitions and provided exclusive coverage of the results: Paris–Roubaix, Bordeaux–Paris, Paris–Brest–Paris. The three were one-day cycling events that Le Vélo helped organize and run. By offering readers exclusive interviews with the contestants and by following the cyclists on each section of road, Le Vélo encouraged nonsubscribers to pick up the paper on race days. Some, they hoped, would even subscribe after seeing the surrounding reporting.

The one-day cycling races worked well for the newspaper’s aims: the races didn’t require much in the way of logistics and took place on regular roads instead of in stadiums—for-profit companies themselves that would have their own ideas about coverage. The events appealed to competitive cyclists but also attracted amateurs. Races any longer than one day would be difficult for cyclists who didn’t train for endurance. On a longer race, registrants would flag, but the sponsoring newspaper could extend the days it offered in-depth coverage. More adventurous than Desgrange, with less to lose, Lefèvre suggested a cycling race longer than anyone before had considered, one spanning France’s entire border. “A Tour de France,” Desgrange clarified.

The Tour had existed as part of French life even if it had never been a cycling race. Kings went on tour to inspect their more distant lands, to let those with tenuous allegiances know that they remembered them; craftsmen left their hometowns for tours to learn how others in regions not their own built cathedrals, baked pastries. Le Tour de la France par deux enfants, a book French children read in primary school, described two children’s journey around their country to find their uncle. A Tour de France race on bikes had never been considered, but it could be imagined. It was enough for Desgrange to not dismiss Lefèvre’s idea immediately.

The editor took the journalist to a café after the meeting and discussed the proposed race further. The pair decided Desgrange would bring the idea to l’Auto’s business director and cofounder, Victor Goddet, for his input. If Goddet thought it impossible, that was easy enough: the idea wouldn’t go any farther. When Desgrange went to him, however, Goddet thought it was just what l’Auto needed.

A Tour de France race on bikes had never been considered, but it could be imagined.

The Tour de France’s first years surpassed Desgrange’s guarded expectations. People left their homes to watch the cyclists on the 1903 Tour’s six stages. In time, the Tour route extended, hewed closer to France’s borders. The cyclists beat the bounds of their country. They marked France’s borders and every town they rode through, in each new clime they reached. As the cyclists biked through some of the same small towns in subsequent years, the association between that town and the Tour grew. The towns formed the Tour, and the Tour formed the towns as well as the country.

Many cyclists didn’t find the Tour appealing at first. It was unquestionably more difficult than one-day events with relatively large purses for the cyclists’ investment of time and training. The Tour was a challenge as much as a race. The average professional didn’t know whether they could finish until they rode back to Paris. Sponsors still promised cyclists’ salaries for the competition, however, and with the smaller prizes along the way, racers could justify the effort. L’Auto and Desgrange’s job were saved. Near the Tour’s end, l’Auto’s circulation ballooned, multiples of Le Vélo’s on its best days. The competing paper shuttered in 1904. Desgrange even became comfortable with the race he had once considered a gamble. He had made it part of his image: the father of the Tour de France. It was his foresight, after all, that let it occur those first years, before its concept had been proven. Géo Lefèvre—who had conceived of the race—was transferred to writing about boxing and aviation while Desgrange stayed involved with the Tour’s administration, covering it in regular dispatches as he followed its route.

On the day of the 12th Tour’s start, June 28, 1914, the archduke of Austria, Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated in Sarajevo. The cyclists were already on the road to Le Havre when Gavrilo Princip fired two shots into the archduke’s car. They rode on even after they heard the news. The race ended on its scheduled day of July 26th. On August 3rd, France entered the war; Tour winner Philippe Thys’s Belgium had already been invaded by that time. With the news, plans for the thirteenth Tour—the event that had saved l’Auto from failure—halted. The race couldn’t hope to cycle along the country’s borders.

Desgrange and the paper couldn’t afford to stagnate until the war had ended, even if the Tour couldn’t take place. L’Auto continued to cover life and sport during the wartime years, even as one after another major sporting event was canceled or held with smaller crowds and diminished competitors. In his columns, H. Desgrange was replaced by H. Desgrenier, a thin pseudonymous veil. The paper’s founding promise of reporting unaffected by politics fell away with the other vestiges of the prewar landscape.

Desgrange’s columns darkened. “This is our work!” he began in his August 15th column, just before Desgrange had turned into Desgrenier. German politicians “alone are amazed to see France draw up against the German brute, they who haven’t bothered to study, for twenty years before the war began, our moral and physical evolution.” He barely distinguished between German leaders and German men who had been conscripted in the fight against France. He continued writing columns supporting France’s decision to fight as the war went on, when his country’s prospects were dim and plenty of other Frenchmen were supporting politicians’ few attempts to resolve the war quickly and peacefully. He continued after he volunteered for the military in April of 1917, at the age of fifty-two, sending his columns back by post. He only let a few close friends and his mistress know his decision. He privately hoped to carry out the mission he had been writing about since the war’s start, to do his part in reclaiming the French lands that had been lost after the Franco-Prussian War and to fight the Germans who would have his country reduced even further.

L’Auto’s front page was at times a small altar to former Tour competitors. The name of a cyclist from the 1914 edition of the race would appear. “Lapize falls on the field of honor,” “Death of Lucien Petit-Breton: the end of a great champion—the accident—his main victories.” In the editor’s bold pen, cyclists who had died in the war were memorialized. Those reading the obituaries were safe behind the lines, celebrating in Paris while their country’s heroes had been brought down in the war. They should remember them, Desgrange wrote in his columns, celebrate them, do anything but forget them.

He ended the obituary of Octave Lapize, the 1910 Tour champion, who had been shot down eight kilometers behind French lines in a dogfight, with one last proclamation: “Hourlier, Comès, Faber, Bouin, Engel! And now Lapize!” he wrote, listing the cyclists killed in the war. “O heroic dead, victims of this Teutonic barbarism, receive splendidly this beautiful son of superb France. He will be, like you, worthily avenged!” Three winners of the Tour had been killed in the war; others had been maimed. Countless not-yet professionals and aspirants who might have someday competed in the race died in the front’s churn.But the war had ended, and the crowd outside l’Auto’s office flocked past.

The people of France, or at least those who read him, had come to expect something from Desgrange: a salve for those preceding years, someone who recognized the hardships they had gone through, would continue to go through, who wasn’t afraid to place blame for those hardships. He was a voice of confidence who could direct their attention, someone who recognized, knew personally, the costs they had endured and the spirit that had stayed with them despite the war’s toll. He couldn’t disappoint them by letting its end pass without comment.

”Ah! My dear country, what suffering we’ve paid to purchase your resurrection,” Desgrange typed. “And what funeral hours next! What grief! The despair we had when the German brute took advantage of us with his methodical planning!” Desgrange drew his conviction from the same source he had found those years back, at the war’s outset, when he’d told French boys to not take mercy on the German soldiers but to shoot them where they stood. “Let us draw a line. Let us live.” He paused once more. “Goodbye to the Boche, and hello to your home!” Desgrange knew some towns along the front would need to be rebuilt entirely. The land around them might never be useful again. Local politicians and whoever chose to return home might find new uses for the fallow ground—more factories, perhaps, like those that had sprung up far from the trenches, supplying the battle lines with all they needed. Bricks or cement could pave over the cratered landscape. People might be able to turn those onetime towns into bustling cities that could supply new factories with the workers they would need. Or the land might stay as it was that day, a memorial spanning hundreds of kilometers where visiting crowds could look in from its edges, few desiring to intrude any farther.

Some towns—Ailles and Courtecon, Moussy-sur-Aisne and Allemant, Hurlus and Ripont and Nauroy and others—were given to the war as martyrs. The government had already deemed them irreplaceable, at least in physical terms. Next to nothing stood where streets once ran through their center. The towns, politicians decided, could be moved elsewhere; they could be re-created with old plans and local memories—whose house stood next to the butcher, which town hall features should be preserved and which were always complained about, and so on—but they couldn’t exist where they once had been. At the Meuse–Argonne, Desgrange had witnessed that putty knife of the war, flattening the landscape and whatever features had once existed. The people wouldn’t leave the war behind; nothing could cause them to do that, not entirely. But maybe their eyes could be directed elsewhere, at least for a time. Let them see that the scarred country still had its strength, its élan, even if that sinew was not what generals thought it to be in the war’s first days.

Nine days had passed since the armistice’s signing. The November 20th edition of Le Temps arrived on newsstands in the morning fog. Headlines said that on Thursday, the German naval fleet would likely be surrendered to the Allies, barring any delays. On the newspaper’s final page, between advertisements for the bookstore Berger-Leverault and Vin de Vial tonic, the editors noted small events not worthy of including on the front page. In two days, poet Jean Richepin would hold a lecture on American life at the Sorbonne; the Société de Auteurs held their general assembly the evening before; the Maisons Laffitte horse track on Paris’s outskirts would enter the final week of its annual season. Small bits of lifelike grass on tilled ground broke through. These scraps were marginal, but they at least existed. Pronouncements and congratulations from liberated towns decorated its borders. Proclamations from foreign leaders, congratulating the French for all they’d done for the world, filled whatever space remained.

Paperboys unbundled and stacked the daily edition of l’Auto at newsstands. An article discussed how Henry Farman, a French airplane designer, had revealed plans for an aircraft that could transport twenty people in its hollow fuselage. The Six Days of New York bicycle race—scheduled to take place in Madison Square Garden December 2nd to 7th—would return after being canceled in the preceding years. Organizers hoped this year’s race could reclaim just some of its previous glory. Robert Dieudonné penned a new short story, “Pot of Varnish,” which Desgrange published. The editor-in-chief’s column appeared on the center of the front page. It still carried the byline H. Desgrenier. The article concerned the project Desgrange had worked on during the war, before he had volunteered for the front: national physical fitness. An announcement, written in fine print to accommodate its lengthy contents, took up the two rightmost columns of the front page and extended four more onto the second. It described plans for an upcoming race, what documents interested cyclists would need to register, their arrival locations in various cities, and the itinerary of what had already been an ambitious race, in what was bound to be, according to Desgrange, its most ambitious edition.

____________________________________________

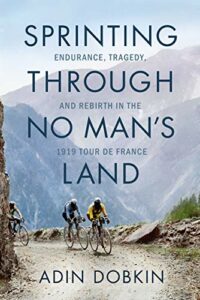

Excerpted from Sprinting Through No Man’s Land by Adin Dobkin. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Little A. Copyright © 2021 by Adin Dobkin.

Adin Dobkin

din Dobkin is a writer and journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, the Paris Review, and the Los Angeles Review of Books, among others. Born in Santa Barbara, California, Adin received his MFA from Columbia University.