How a Naming Ceremony Unlocks a History of Power

Sasha LaPointe on Taking the Skagit Name of Her Great Grandmother

As I waited, my eyes wandered to the large cedarwood cabinet against the wall. I’ve known it since childhood. It used to stand in my great-grandmother’s house, and it contained cedar baskets, carvings, and small talismans. I focused on the small doll on the second shelf, the Sasha Doll. The doll had been gifted to my mother as a child. My grandmother had to special order it from a Swiss doll maker based in Germany.

There were no Native American dolls when my mother was young. Just Barbie dolls and baby dolls, blue-eyed and yellow-haired, but my grandmother had wanted her daughter to have a doll that resembled her. It was the only doll at the time with olive-tone skin, dark hair, and brown eyes. The perfect Indian baby, one my mother could hold truly as her own. Imprinted on the doll’s back in bold letters was SASHA. This is how my mother named me. This doll was my first namesake.

When I was a child I was obsessed with the Sasha Doll; I asked to take her to show-and-tell. I was proud of this strange girl, this relic whose name I bore. But I have always been a clumsy girl, and when I brought the doll to my first-grade show-and-tell, I dropped her on the pavement. When I picked her up I saw her arm had broken off. I was beside myself with shock. I picked the pieces up and tried to shove the arm back into its delicate socket. I held the two pieces together with all my might, thinking they might magically fuse back together. I can fix you, I thought. I can fix you.

To my horror the doll had to be taken to the doll hospital, to mend what had been broken. The doll doctor did what I could not and put her back together again. After she was fixed the doll and I became estranged. I’d failed her. With shame I watched my mother take the doll back and put her on the shelf. I never touched her again.

In addition to the Sasha Doll, the shelf housed cedar baskets, paintings, and old photographs. One photograph in particular my mother had shown me before. It featured a woman in silver and sepia tone standing next to a river. She looked strong. She was proud and sturdy and beautiful. “This is your great-great-grandmother Louise,” my mother told me when I was ten. “Your great-great-grandmother.” Louise was my middle name. In contrast to the woman in the photograph, I was a pale, distractible thing. Surely there had been a mistake. “You come from a long line of strength,” my mother assured me. “You carry it in your name.”

I like to think my great-grandmother knew what she was doing that day, that she knew the countercurse I would someday need.

The very vessel that held all of these artifacts came from another woman whose name I carry. Louise’s daughter, my great-grandmother, Violet taqʷšəblu Hilbert gifted me her Skagit name. To be a namesake is a great responsibility. “You’re my namesake and you’re going to do important things,” she would say to me.

There is a photograph of me at my naming ceremony, small in a blue dress, mess of brown ringlets falling around my face as I teeter precariously close to the edge of a picnic table. The photo was taken in 1986. I am three years old. My arm is outstretched as if reaching for someone out of frame and I’m smiling. I’d like to think it was my great-grandmother just out of reach, coming to gather her namesake up in her arms, but there is no way of knowing. It could have been my mother. It could have been anybody. I have white socks with ruffles and strappy shoes.

You can tell from the photo that my mother wanted me to look nice. You can also tell by the grin on my face that moments after the photo was taken I would be barefoot, that my dress would be streaked in grass stains. When remembering that day, my mother sighs, laughs a little, and says, “I looked across the yard, saw you on the table dancing next to a boombox, and I just knew you were going to be a handful.”

That day relatives passed me along in their arms. As uncles tended to the fire, as the salmon baked, friends and family tousled my hair, pinched my cheeks, and said things like “taqʷšəblu number two” and “What hard shoes to fill!”

I like to think my great-grandmother knew what she was doing that day, that she knew the countercurse I would someday need. Like the fairy godmother in Sleeping Beauty who saved her gift for last and passed to the sleeping princess the only thing that could wake her.

As a child I would long for what princesses possessed: magic, courage, enchanted slippers, and the love of brave princes. I would come to yearn for new worlds and ways to escape. What I wouldn’t realize was the power that was bestowed upon me that day, the magic my great-grandmother passed down. And it wasn’t true love’s kiss. It wasn’t a prince. It wasn’t a spell or a slipper. It was a name: taqʷšəblu. Like an incantation.

Tock-sha-blue. It comes from deep in me. Travels through parted lips out into the world and stays there.

__________________________________

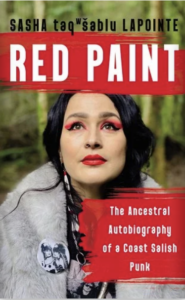

Excerpted from Red Paint: The Ancestral Autobiography of a Coast Salish Punk by Sasha LaPointe. Published with permission of Counterpoint Press. Copyright © 2022

Sasha LaPointe

Sasha taqʷšəblu LaPointe is a Coast Salish author from the Nooksack and Upper Skagit Indian tribes. She received a double MFA in Creative Nonfiction and Poetry from the Institute of American Indian Arts. She lives in Tacoma, Washington.