How a Mutiny on the Somers Changed America

“No case of the century, prior to the assassination of President Lincoln, aroused as much interest and passion.”

I’m fortunate to have spent much of my career at American Heritage magazine, whose spacious franchise is everything that ever happened on this continent. I’ve also written some popular (or so I hoped) histories on various subjects — the Battle of the Atlantic in World War II, Henry Ford, the creation of Disneyland, and when in the spring of 2020, the COVID virus settled in for its long stay, I was searching for a rich source from which to mine a book.

One morning I woke up with the word or name ”Somers” in my mind. It struck a distant American Heritage chord, and I went to the magazine’s valuable web site and found an article called “Panic on the High Seas,” which had appeared in 1961, drawn from a book by Fredric F. Van De Water, The Captain Called it Mutiny.

As I read the story both titles came to seem increasingly appropriate.

Here’s what I found out:

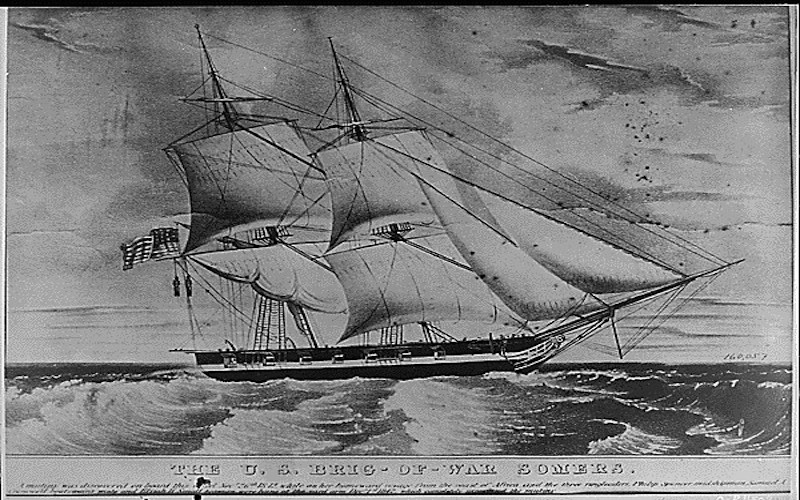

On the evening of December 14, 1842, the United States brig-of-war Somers sailed into New York Harbor at the end of an unusual voyage. Our modernizing Navy was looking to shed some old traditions, among them the ancient way of training its sailors, which had always been simply to drop them aboard a ship. To be sure, any adolescent could learn plenty about his new life by going through even a single storm at sea, but the Navy was outgrowing its learning-by-doing youth. The Somers had been chosen as America’s first seaborne school, dedicated to offering young sailors systematic training rather than hoping they’d simply absorb it during the course of the working day.

But this worthy aim was not what had made the Somers’ voyage remarkable. Her captain, Commander Alexander Slidell Mackenzie, came ashore into the Brooklyn Navy Yard with astonishing news. The shipful of teenagers under his command had almost carried off a mutiny that would have left many of the 120-man crew murdered, along with all but one of the officers. That was just the beginning. The mutineers would then have turned the Somers into a pirate ship (she would make a perfect one: with her 10 heavy guns she could outfight any merchant ship and, being perhaps the fastest vessel in the American service, outrun any warship).

In the New York of the 1840s, a town whose life was nourished by the sea, pirates were not the chummy rapscallions one can visit today in a Disney park: they were remembered as well-armed, well-trained bands of assassins that specialized in arson, maiming, plunder, murder, and rape.

So thank God for Captain Mackenzie, who staved off calamity, said the New York Herald-Tribune, “with a boldness and decision” that “can only be paralleled in the early history of the Roman Republic.”

The Herald’s rival Enquirer added to the praise sparkling through the entire city press: “Sufficient is known already to establish a beyond a question the necessity, imperative and immediate, however dreadful, of the course pursued by commander Mackenzie, than whom, a more humane, conscientious and gallant office does not hold a commission in the navy of the United States.”

But what was “dreadful” about Mackenzie’s course? He’d hanged three of the mutineers: harsh, certainly, but surely better than losing the Somers, most of her crew, and then the other ships the newly-minted pirate ship would have attacked.

There the matter might have rested had not a letter appeared a few days later in a Washington, D.C. newspaper.

Captain Mackenzie’s account of the events had his ship simmering on the verge of combustion, with every passing day bringing the crisis closer, until, at the last possible hour, he destroyed the mutinous beast.

The new letter told a different story: the accused head of the plot had been in double irons at the time of the executions, so closely confined that he couldn’t have stood upright, let alone lead an uprising; that the ship had been cruising in perfect peace for days through the densely-populated Virgin Islands whence help could have been summoned in a few hours if needed; that there had been no disturbances among the crew when the three mutineers, Boatswain’s Mate Samuel Cromwell, Seaman Elisha Small, and Acting Midshipman Philip Spencer, were noosed and hanged.

The letter’s tone was crisp and calm throughout, setting forth its account with lucid economy, never suggesting the writer had any personal connection with the events it detailed. Save for one sad hint: of Philip Spencer the writer says that the paper gave his age as “over twenty. Had he lived, he would have been nineteen the twenty-eighth of January next.”

The letter was signed only with a cryptic initial “S” but the identity of its author soon got out: He was John Spencer, one of the most powerful legal minds of his day and President John Tyler’s secretary of war; Philip Spencer was his dead son.

No chance now that the story would soon blow over; rather, as the great naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison remarked, “No case of the century, prior to the assassination of President Lincoln, aroused as much interest and passion.”

The case revolved around its two principals, Captain Mackenzie, who had carried out the death penalty arrived at by a council of his officers that he had convened in a sort of mock-court martial, and Philip Spencer, whom he believed to be the chief conspirator.

Mutineer or not, Spencer was a difficult fellow, moody, slyly insolent, surly to his fellow officers but overly gregarious with the crew. His academic life had been lethargic enough for his father to send him to sea; about the most constructive thing the boy had done as a student was to donate to the school library a lurid history of buccaneering called The Pirate’s Own Book.

Pirates and piracy had long fascinated Philip Spencer. The hobby cost him his life.

Captain Mackenzie’s account of the events had his ship simmering on the verge of combustion, with every passing day bringing the crisis closer, until, at the last possible hour, he destroyed the mutinous beast.

A couple of months into the voyage he waylaid the ship’s assistant purser, James Wales, swore him to secrecy, and, with the two crouched in one of the few corners of privacy the small brig afforded, said that Spencer and his confederates would seize the ship, swing the guns inboard to cover the decks, butcher the officers, and lead those crewmen who had been allowed to keep their lives into a paradise of looted treasure and fragrant tropical isles. He would make Wales one of his officers. Did that please the purser?

Wales said it did. Then, as soon as he could get away, he hurried to tell the first lieutenant, Guert Gansevoort (American literature is in this officer’s debt, as he persuaded his cousin Herman Melville to go to sea). Of course Gansevoort immediately reported the plot to Captain Mackenzie.

Who thought it was a joke. The scheme, he said, “seemed to me so monstrous, so improbable, that I could not forbear treating it with ridicule. I was under the impression that Mr. Spencer had been reading some piratical stories, and had amused himself with Mr. Wales.”

This mature and rational response was fleeting. In a matter of hours the captain was seeing ominous signs everywhere. He took no comfort from the presence of his officers, whom he soon had on night-long armed patrol, regularly pacing past Midshipman Spencer, now chained and sitting on an arms chest, while rumors crackled throughout the vessel and a miasma of panic began to rise from its planks.

But there was no mutiny. The three accused ringleaders were hanged and buried at sea, and the Somers returned to a storm of publicity, a court of inquiry, and a court-martial of Captain Mackenzie.

The court of inquiry was just that: an exercise to determine facts; it could prefer no charges. The court martial, on the other hand, put Mackenzie on trial for his life. It is a little surprising how eagerly the captain pushed for it, until one sees that Philip Spencer’s father was doing his formidable best to get his son’s executioner in front of a civil rather than a military court.

The elder Spencer was sure a naval trial would go easier on one of its own, and that is what happened. The captain wasn’t exactly exonerated, but the case was found “not proved.” The Navy’s feelings about it are reflected by the fact that for a generation the Somers mutiny was a taboo subject at officers’ mess-table discussions.

After a few weeks of reading I found myself wondering if there was a book in this. True, it was the U.S. Navy’s only mutiny (if mutiny it was); and the incident did lead directly to the founding of the U.S. Naval Academy which, a century later, proved the seedbed of the most powerful fleet the world has ever known. Nevertheless, I was worried that it might boil down to a mere anecdote, and a rather depressing one at that.

As I started on the book in earnest, I immediately encountered two sources whose value I was too dense to spot quickly.

The first came from Captain Mackenzie himself. It turned out he had written in the 1830s a highly popular book about his travels in Spain. The Navy has long been a bit suspicious about seafaring authors unless their subjects are gunnery or estuaries, but two centuries ago the service was proud enough of Mackenzie’s success to order copies of his Spain book put aboard every U.S. warship along with Nathaniel Bowditch’s Practical Navigator.

Well, good for Mackenzie. But this didn’t make me any more eager to read a three-volume (!) collection of archaic travel reminiscences. And, by God, once he’d finished with Spain the captain had sat down and given England the same treatment.

It took me a while to realize what a singular stroke of luck this was for me. So much that happened aboard the Somers on her lethal cruise flowed from the captain, and here I was studying a long-dead, mid-level naval officer who had bequeathed me hundreds of pages of first-person narrative from which to tease clues about his character and personality.

They were certainly there. One example may suffice.

Captain Mackenzie is patriotic; the book swarms with tributes to the American flag; he is energetic and observant; he is unfailingly moralistic. There is little from which a reader might predict the catastrophe to come when he took Philip Spencer aboard.

Yet here and there he shows a relish for violence that approaches the prurient. Outside of Tarragona, highwaymen stopped Mackenzie’s stagecoach. The driver gave them his purse and begged for his life. Instead, one of the bandits began to beat him on the head with a rock. Writes Mackenzie, “…The murderer redoubled his blows until, growing furious in the task he laid his musket beside him, and worked with both hands upon his victim. The supplications which blows had first excited, blows at length quelled; they had gradually increased with the suffering to the most terrible shrieks, then declined into low and inarticulate moans, until a deep-drawn and agonied gasp for breath, and an occasional convulsion, alone remained to show that the vital principle had not yet departed.”

Meanwhile, a second robber set about Pepe, the mule boy, with a knife, the blows described with unsettling thoroughness: “I could distinctly hear each stroke of the murderous knife, as it entered the victim; it was not a blunt sound, as a weapon that meets with positive resistance, but a hissing noise, as if the household implement, made to part the bread of peace, performed unwillingly its task of treachery.”

Although a priest in the carriage “hid his face within his trembling fingers,” Mackenzie’s “own eyes seemed spellbound, for I could not withdraw them from the cruel spectacle.”

Of course he was an unwilling witness. But at other times he sought out such spectacles. He attends a public execution in France, “and the feeling of oppression and abasement, of utter disgust, with which I came from it, such as to make me form a tacit resolution never to be present at another.”

That resolution lasts until he reaches Madrid, where he sees “a short notice that the proper authorities would proceed to put to death two evildoers,” and goes on to give a ten-page account of their hanging.

Once again, remorse and disgust. And once again he then takes himself to witness another death, this one a garroting: “It was sure to be a spectacle full of horror and painful excitement; still I determined to witness it. I felt sad and melancholy, and yet, by a strange, perversion, I was willing to feel more so.”

One does remember Captain Mackenzie’s execution tourism as he orders his three mutineers hoisted from the deck of the Somers.

The value of another crucial source was at first opaque to me, and here my reluctance came from simple peevishness about having to read tiny type. But that was all there was on offer in the pages of the transcripts of the court of inquiry and the court-martial.

At least it did not take me long to realize that for the small price of having to squint I was able to eavesdrop on what people actually said. Any newspaper of the 1840s, in reporting a harsh conversation, would run something like “he rounded on his adversary with an oath…” In a trial transcript, he will call him ”a son of a bitch.”

The language lives on the page. Here is Wales giving damning testimony about Spencer, having been asked if the midshipman had said anything of his plans for “the small boys” aboard the Somers. “Yes, sir; he said that small fry eat a large quantity of biscuit, that they were a useless article aboard a vessel, and that he should make ‘way with them.” And on Spencer trying to curry favor with the crew: Wales had seen him “hand out two bunches of segars at a time…And I have seen him give tobacco and segars to the smaller boys, saying, when he gave it to them, that ‘he knew it was contrary to the rules of the vessel to give it to them, but if the commander would not let them have it, he would accommodate them.’”

Here Midshipman Perry, of the famous nautical family, grows passionate when asked if the Somers could have gotten help from a friendly port. “It was discussed as to whether she could be taken into St. Thomas, and I, in answer, said I would rather go overboard than go into St. Thomas for protection—that I would never agree to a thing of that kind.”

Why?

“Because I thought it would be a disgrace to the United states, the navy, and particularly to the officers of the brig; my reasons were that if an American man-of-war could not protect herself, no use in having any.”

Despite their minuscule type, these transcripts were a godsend, their energetic question-and-answer format helping to lend momentum to the narrative.

My book is finished and, for the moment at least, Covid has subsided. But sometimes, when I’m on the fringes of sleep, I still hear those distant voices.

_____________________________

Sailing the Graveyard Sea: The Deathly Voyage of the Somers, the U.S. Navy’s Only Mutiny, and the Trial That Gripped the Nation by Richard Snow is available from Scribner.

Richard Snow

Richard Snow spent nearly four decades at American Heritage magazine, serving as editor in chief for 17 years, and has been a consultant on historical motion pictures, among them Glory, and has written for documentaries, including the Burns brothers’ Civil War, and Ric Burns’s award-winning PBS film Coney Island, whose screenplay he wrote. He is the author of multiple books, including, most recently, Sailing the Graveyard Sea.