How a Guesthouse in Florida is Creating a Trans Community

A Visit to the Only Retreat Dedicated to Gender-Nonconforming Clients

Four guys are sitting on voluptuously padded recliners watching Breaking Bad on a huge flat-screen television with their legs elevated and drains attached to their chests. A copy of GQ with a cover of Katy Perry showing lots of cleavage is strewn on the coffee table. Meanwhile, their caregivers are busy preparing lunch in the nearby communal kitchen.

Tristan, a blonde former navy lieutenant from St. Petersburg, Florida, is here with his mother, Theresa, who is in her late sixties. He has two tattoos on his shoulder blades: one that says momma’s baby and the other that says daddy’s girl.

There’s a couple from Calgary, in Canada: Len just finished college, and Linda works as a drug treatment counselor. Both are 23, from Chinese immigrant backgrounds, and have been best friends since they were ten years old, and romantically involved with each other for the past year.

Len saved for a year to be able to afford surgery, placing loose change and spare bills from tips he made as a restaurant server in a box every week. They’re both from large Asian families who have not been accepting of their choices, yet they’re living at home, waiting for the day when they can afford to move in together. And there is Jackie, from London, who is here with his best friend, Christian, a gay man.

New Beginnings Retreat, an 8,900-square-foot pink Spanish-style stucco house in a gated community in Broward County, Florida, is the only accommodation in the United States, and probably the world, that caters exclusively to transmasculine and gender-nonconforming clients, most of whom are undergoing chest masculinization.

“Guys deserve to recover in privacy among each other,” says Leland Koble, who established the guesthouse in 2011 with his wife Bonnie, a nurse. Six to eight guests stay here for a week at a time. For $124 to $144 a night they get a room with two beds and a bathroom, access to a shared kitchen, transportation to all doctor appointments, and an instant community.

Leland and Bonnie talk about forging a “brotherhood” among young transgender men in transition. A map of the world hanging on a wall in the living room is covered with pins that mark guests’ places of origin. Most states in the nation are represented, with a denser concentration on the two coasts, and especially in the South, Europe, Canada, and Australia. China, Japan, and even Mauritius are pinned too.

The guesthouse offers individuals undergoing top surgery practical help during the recovery week, but it also offers social support and an opportunity to bond with other budding men—and their largely female caretakers. Sally and her partner, Pete, who are both in their mid-twenties, have come from Topeka, Kansas. They were in a lesbian relationship until Pete decided to transition a few years ago.

Billy, from small-town Tennessee, is here with his fiancée, mother, and grandmother. While he declined to be interviewed, his mother, who is about 40, tells me that some people in her church “object to changing one’s sex.” They believe that “God made them this way,” she says. “But if you had children who were Siamese twins, wouldn’t you try to correct it?”

All had gone to great lengths to save for surgery, and received little or no help from their families. They work as insurance adjusters, restaurant servers, and technicians. For the most part, they live in the regions they grew up in and want to stay there if they can, because they’re hooked into their families, if they’re lucky enough to have families that accept them, or they simply have no place else to go. It’s all worth it, they believe. They’re out as transgender to those closest to them, and they are careful about whom they share that information with. Some have managed to successfully integrate their gender transition into their work lives. Others are not as fortunate.

“[New Beginnings] doesn’t advertise its presence in the community, but the very fact that it is here, nestled in a gated community comprising upper-middle-class families, is a bold act.”

Pete and Len were forced to take time off and retool themselves. Although it is now more possible for transgender men to openly disclose their intention to transition and still keep their jobs, that is not true across the board. (Fifteen percent of transgender people surveyed in 2015 reported that they were unemployed, at least three times the national average; the unemployment rate was highest among transgender people of color).

New Beginnings is, like many of the individuals who stay here, one local activist tells me, “stealth in plain sight.” It doesn’t advertise its presence in the community, but the very fact that it is here, nestled in a gated community comprising upper-middle-class families, is a bold act. In the past, individuals would show up in San Francisco or Philadelphia for surgery and “crash on each other’s couches” and care for one another, says Ben Singer, a longtime activist for transgender health. Its relative luxuriousness, and indeed its very existence, is a sign of the growing clout of the transmasculine population.

For Leland, the guesthouse, which in its five years of existence has accommodated more than 600 individuals, is a business as well as a calling. “If you’re doing it for the right reasons, and your motivations are right, money and stuff come to you,” he says. “I don’t have to think, ‘I have to make X amount of dollars this year to survive!’ You know what I’m saying? It just rolls for me, and it has always been that way. I’ve always been fortunate.” The guesthouse is run as a nonprofit corporation. Guest fees cover the bulk of its operating expenses, and donors make up the difference.

In addition to the guesthouse, there is a chest binder exchange program; a “big brother support system,” placing former patients in touch with one another; a physician and therapist referral network; and a safe house for transgender people in “desperate need of housing and a place to start over.”

Leland, who is in mid-fifties, is stocky, has short-cropped hair, and projects authority. A thick gold chain loops around his neck, and he is wearing square silver-rimmed glasses, a Lacoste shirt, and baggy blue jeans. As we talk, phones ring, deliveries pile up, and guests mingle in the kitchen. “A couple of guys need to be picked up at the mall,” he tells Bonnie. “Okay, sir,” she replies. When they first got together 12 years ago, Bonnie asked whether she could call him “sir,” to which he replied: “I like that. It’s got a nice ring to it,” and she has called him that ever since.

The idea of establishing a guesthouse for those who are altering their female bodies occurred to Leland as he was sitting in a waiting room waiting to consult with a plastic surgeon to have his own breasts removed. Leland grew up as a girl in small-town Iowa, population 1,000, in the 1960s and ’70s. “I was not like all the other girls,” he says. “I identified as a boy. When I turned 12, developed breasts, and got my period, I knew it wasn’t me. I always felt more comfortable as a boy than a girl.”

While he was waiting to speak with the surgeon, someone from Italy and “someone from England, or something like that” were in the waiting room talking about the challenges of arranging transportation and hotels during their surgery week, Leland remembers. Then one day, as he recovered at home, it came to him. “I think I have a great idea,” he said to Bonnie. “I want to start a guesthouse for people transitioning.” So he went out and found a house to rent—a mansion, really—put a business plan together, and it worked. “I’ve always been the kind of person that attracts people in the sense that I’m a competent person. I have an idea, I set my mind to it, I do it. That’s it.”

*

A few of the people who are staying here have biceps, covered in elaborate tattoos, which rival those of the most dedicated cisgender male bodybuilder. There is something both deeply subversive and at the same time traditional about this place.

“All the muscle flexing and displays of testosterone-fueled hair growth one finds here at times is for a good cause, says Leland: it builds brotherly ties.”

Marriage seems to be very important to many of those who come here. When you enter the house, the first thing you see is Leland and Bonnie’s framed marriage certificate, lovingly placed next to an autographed photograph of Michael Jackson and one of his gloves. For another thing, a number of the guys I met here are trying very hard to be, well, guys.

Even though he is clearly experiencing discomfort, I overhear one pumped-up guy talk about the surgery he had the day before: “Piece of cake,” he brags, “though I’m glad I don’t have to do it again!” he says with a smile. The day after his bandages came off, Tristan, who had 38C breasts, proudly shows off as though they were battle scars the deep red lines that shot across his chest. All the muscle flexing and displays of testosterone-fueled hair growth one finds here at times is for a good cause, says Leland: it builds brotherly ties. Particularly during the early part of the transition process, some trans men try to emulate the appearance, manners, and habits of hypermasculine cisgender men in order to prove to others (and themselves) that they’re men too.

Those who come here to embrace their inner maleness are lovingly cared for by their wives, girlfriends, and mothers. A mother from Orlando, Florida, writes in the guestbook: “This week is epic in my son’s life. He says it’s like a dream. I say it’s a magical reality long awaited. NBR have provided the perfect retreat for this dream come true. As a mom, I never worried thanks to you. Moms worry even when there’s no surgery involved. My son, his fiancée, and I feel renewed here. You have taken the fear out of recovery. What you are doing here is a blessing to us all.” She signed her name with a peace sign and a heart.

When I ask Sally from Topeka what drew her and Pete here, she says, “I’m just supporting my husband.” Sally and Pete have been together “going on four years,” she says. At first, she considered herself a lesbian—when she was in college: “you had to take on a label,” she says. She was never a “gold star lesbian,” exclusively dating women. Now those labels matter even less, she says. Since she and Pete got together, they haven’t really been a part of a queer, or trans community. “It has always been just the two of us doing our thing,” she says.

Many of those who stay here say it’s the first time they’ve encountered other transgender men. In one testimonial, a guest writes: “I made lifelong friends with people who I’m happy to call my brothers, my fellows, as well as their partners and parents. I felt as though I finally belonged somewhere.” Lex, visting from Southern California, writes in the guestbook: “The opportunity you offer is such a great experience, especially for those who seem alone in this journey,” who do not have a support system to help them through the transition process.

Sally, who works for mental health services for the state of Kansas, tells me she appreciates the “happy vibe” at the house. At home outside of Topeka, she says, “we don’t fit in any part of the queer community really. And unless we become really verbal about what we are, who we are, where we come from and all of that, we won’t fit into that.” They would like to be out one day about their history and the fact that Pete is transgender, but they can’t be. It would jeopardize their jobs.

Pete worked as a corrections officer before he went to college and became a customer service representative for a financial services company. In his spare time, he does powerlifting and Olympic lifting at a local gym, but he had to quit his job in order to transition. His health insurance didn’t cover top surgery anyway, so they’re paying out of pocket. “We’ve just kind of been squirreling money away,” says Sally, and “couponing.” And they sold their extra vehicle to help raise the cash. They’re planning to have kids within a year or two, once they become more financially secure.

“Top surgery changes their lives for the better,” Leland says of those who have stayed here. “They seem to be very productive, much happier. A few are even having children.”

For all his good-natured bluster, however, when it comes to how he sees himself in the gender landscape, Leland is more equivocal. “I’m not really a woman. But I’m not trans either,” he says. He doesn’t take testosterone to masculinize his voice or face because his cardiologist recommended against it—the doctor said it would increase his chance of having a heart attack, so he says, “I’m staying in the middle. I have a woman’s body from here to here,” he says, pointing from his waist to his toes. “There, I’m my mother.” But when it comes to his chest on up, he says, “I’m my dad.”

“I don’t know if I identify as trans.” If he were younger, he probably would, he tells me. Instead, he just wants to help those who feel similarly estranged from their bodies.

“It’s not an easy place. I’m not in an easy place. People say, shit or get off the pot. Go one way or the other, and I’d be much better. I’m in a very confusing place for everyone. No one gets it. They’re like, ‘What? Are you a boy or a girl?’ But I just identify as me.”

__________________________________

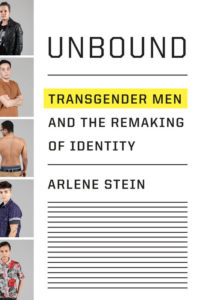

Adapted from Unbound: Transgender Men and the Remaking of Identity. Used with permission of Pantheon. Copyright © 2018 by Arlene Stein.

Arlene Stein

Arlene Stein is a professor of sociology at Rutgers University and director of the Institute for Research on Women. The author of six books, she received the Ruth Benedict Prize for her book The Stranger Next Door. Her most recent book is Unbound: Transgender Men and the Remaking of Identity. Stein has written for The Nation, Jacobin, and The New Inquiry, among other publications. She lives in New Jersey.