When the phone rang early on June 5, Marjorie “Hiddy” Spock had been hoping for better news. Instead, Mr. Kilgallen from the local agriculture office told her that the spray planes going out the next day would pass near her home in the morning. Despite her many requests, he just couldn’t promise that her two-acre property in Brookville, Long Island, would be spared. Spock hung up and acted fast. She packed her partner, Polly, into the car and drove her to a hotel in New York City.

Back home that afternoon, Spock pulled out the massive plastic sheeting she had bought just in case. She spread it over their vegetable and herb gardens, the fruit trees in their orchard, and the dozens of berry plantings all over the property. It took ten hours, but by midnight everything was covered.

The next day, at work, Spock began to worry about her plants wilting under the plastic’s heat. At lunch she rushed home to pull off the sheets. When she got there, they were dry. She felt a wash of relief; they hadn’t been sprayed after all.

Two days later, though, she was having breakfast when she heard the roar of an airplane engine. Stepping into the yard, she saw a low plane passing out of view. Brookville’s tall, woodland trees meant she couldn’t track it very far. But the plane returned a few minutes later, again a few minutes after that, and then again and again. She counted. The plane passed overhead fourteen times before it disappeared, leaving the smell of kerosene thick in the air.

She knew that smell meant DDT.

The plane was one of dozens commissioned to spray Long Island with DDT in the spring of 1957. The pesticide was the cornerstone of a federal program targeting the gypsy moth caterpillar. The hungry, fuzzy-headed caterpillars had been imported to the US back in the nineteenth century by a hobby scientist hoping to start a silk industry in Massachusetts.

The industry didn’t take off, but the caterpillars did. They multiplied at such a clip that by the 1880s, local residents said they could hear the sounds of them crunching and the patter of their excrement hitting the ground on summer nights. The caterpillars spread from there, feasting on the leaves of shade and fruit trees. In particularly bad summers, they stripped whole swaths of New England forest and woodland bare.

For decades, entomologists tried to limit the caterpillars’ damage and spread. They lit them on fire, hand-picked their eggs off trees, imported predator insects from Europe, and hit infested trees with lead arsenate. The caterpillars persisted. Then, in the late 1940s, a few scientists in Pennsylvania tried spraying affected trees with DDT. The caterpillars disappeared.

Successful experiments in Massachusetts and Michigan followed. Emboldened by the results, in 1956 the USDA announced a program that would spray three million acres of northeastern moth habitat over five years. Spray season would begin each May, by plane, to reach eggs deposited high in woodland canopies right when they were hatching. This, the USDA promised, would eradicate the caterpillar once and for all.

When Spock heard about the spray plans, she called the USDA’s local plant and pest control division in nearby Hicksville right away. The office’s supervisor, Lloyd Butler, was out, so she left the first of what turned out to be many messages with his secretary.

She spent the next six weeks writing letters and calling USDA offices on Long Island and at the state capitol in Albany. She begged not to be sprayed. She offered to prove that her property had no caterpillars. She asked for mercy: Polly was sick, and their spray-free vegetables, fruit, and dairy products were vital to her health. But no one—except maybe Kilgallen—seemed to care. As the spray date approached, she wasn’t quite sure what to expect, but she was not at all prepared for fourteen unannounced passes of a spray plane in a single day.

Not long after that June morning, the damage Spock feared began to set in. Their four hundred feet of pea plantings browned and died before bearing fruit. Raspberry and strawberry plants withered. Beet, chard, and lettuce leaves were shot through with holes. Pests that Spock had never seen before in their garden—potato scale, red spider mites, and slugs—suddenly turned up in droves. The wood thrushes, once numerous around their home, were gone.

She despaired over what Polly should eat and how to keep Polly’s illness from coming back. She sent a sample of their soil to a laboratory she knew of in the city to have it tested for DDT. She later sent some beets, too. The spray, she thought, was a “poisonous trespass.” Friends told her not to, but she had made up her mind: she was going to sue the government.

She begged not to be sprayed. She offered to prove that her property had no caterpillars. She asked for mercy: Polly was sick, and their spray-free vegetables, fruit, and dairy products were vital to her health.Spock had found herself on Long Island with Polly after two decades of teaching and running some of New York City’s finest private schools. She had grown up as the tall, hardy, and spirited second- youngest child of a large and well-to-do New York family. Her father was the esteemed attorney for the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad. Her older brother Benjamin had grown up to become the nation’s most famous pediatrician.

Spock herself was admitted to Smith College after high school, but she had gone to Dornach, Switzerland, instead, against her family’s wishes, to study at an institute run by philosopher Rudolf Steiner. She fell in love with Steiner’s teachings about spirituality, humanity’s connection to the Earth, and human development (Steiner created Waldorf education), and she stayed for years. She had run into Polly there—they had known each other as teenagers in New York—but it was just a passing encounter. When Spock’s father died in 1931, she left Switzerland and went back home to New York.

Spock ran into Polly again two decades later, at a Waldorf conference in New Hampshire. Spock was astounded by how little her old friend resembled her younger self. Polly, in her early forties then like Spock, was pale and shockingly thin. Spock was sure she could not have weighed a hundred pounds. Polly shared the story of her illness: for years, she had suffered gastrointestinal symptoms so severe they confined her to bed for days at a time. Grocery and restaurant food seemed to trigger it. Unable to eat, she had grown thinner and weaker. But Spock still found her charming, with a radiant warmth. Drawn to her, she offered to get Polly a teaching job and help her build up her strength.

They bought the house in Brookville together in 1951. On a physician’s recommendation, they began to grow their own food. Polly spent less and less time in bed. She put on weight. Her complexion warmed. Spock believed she was healing. She could not imagine losing those gains. When she decided to sue the government, it was to protect Polly. But it was also a decision they made together, because it was Polly’s family money they would use to cover the costs.

It wasn’t terribly difficult for the two women to find a lawyer. But it surprised Spock how easy it was to find other Long Islanders eager to sue. The retired curator of ornithology at the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan, Robert Cushman Murphy, had a home not far from theirs, in Oyster Bay. He was incensed that the spray had killed the minnows he had bred to eat mosquito larvae in his ponds. He joined Spock’s suit and knew of others who would, too.

He connected Spock with banker J. P. Morgan’s daughter, Jane Nichols, who owned dozens of acres of cropland and dairy pasture in nearby Cold Spring Harbor. He also put Spock in touch with Teddy Roosevelt’s son, Archibald Roosevelt, an army colonel and wildlife defender who lived in the same moneyed enclave. Before long, Spock had more than a dozen enraged plaintiffs and lawyers from a firm of Princeton grads in the city.

Long Island’s spraying might be complete, he pointed out, but it was just the start of a five-year program, one that violated the Fifth Amendment.Spock took the lead organizing the plaintiffs into the Committee Against Mass Poisoning, CAMP for short, headquartered in the basement of her and Polly’s home. When school let out for the summer, she researched DDT full-time, collecting scientific papers, government reports, and newspaper and magazine articles about the pesticide. Polly’s illness began to make more sense to her than ever. One doctor she found, Morton Biskind, had documented similar symptoms in hundreds of his own patients. She wrote to him right away to ask if he would be willing to explain DDT’s hazards in court. He was happy to share his papers, he said. But he wasn’t interested in being a witness. He had testified in the Delaney hearings several years before, he told Spock, and the attacks on his reputation and credibility that followed were not something he cared to face again.

Biskind pointed Spock to some of his colleagues instead. Gradually, she amassed a list of impressive doctors and scientists willing to testify. Two were physicians convinced, like Biskind, that pesticides were making their patients ill. Another had actually measured levels of chlorinated hydrocarbons in his patients’ bodies since 1950 and had found them steadily climbing. But Spock was most excited about two other witnesses: Malcolm Hargraves, a physician at the Mayo Clinic whose research showed that pesticide exposure appeared to cause leukemia, aplastic anemia, and Hodgkin’s disease; and Wilhelm Hueper, a National Institute of Health scientist who was one of the nation’s top experts on chemicals harmful to human health. “With the scientific data now assembled,” Spock told a friend, “we should win in a walk.”

Later that summer, Spock’s lawyer, Roger Hinds, introduced a motion in the Eastern District Court of New York seeking a permanent injunction against DDT aerial spraying. It named Lloyd Butler, New York State agricultural commissioner Daniel Carey, and US secretary of agriculture Ezra Benson as defendants. Lawyers for the defense asked the judge to dismiss the motion, arguing that the spraying was already complete. Hinds argued for a trial: Long Island’s spraying might be complete, he pointed out, but it was just the start of a five-year program, one that violated the Fifth Amendment by depriving plaintiffs of property and possibly lives without due process of law and by taking their private property for public use without just compensation. It also violated the Fourteenth Amendment, he argued, via illegal trespass on private property. The judge agreed to hear the case. And in February 1958, Spock and her plaintiffs went to court.

Never, he said, would anyone have suggested that alcohol consumption be compulsory. But the plaintiffs had been forced to consume DDT “against their will.”A blizzard hit the Northeast the night before the trial, blanketing Brookville under several feet of snow. When Spock woke that morning, the streets were impassable. Their house was more than a mile from the closest train station, but she didn’t dare miss their day in court. She had arranged to take two weeks off of work, and Hinds had encouraged her to bring to court the masses of material evidence she had collected: scientific papers, government reports, news items, and letters from citizens opposed to the spray campaign in other states. She tucked a thick stack of files under each arm and trudged to the station through the still-falling snow.

When she arrived at the US District Court in Brooklyn, just minutes before Judge Walter Bruchhausen called for order, Spock was nerve-racked—but also optimistic. Three judges who had heard the plaintiffs’ motions to date had all ruled in their favor, allowing the case to come this far. The case had been given calendar preference too, putting it ahead of a two-year backlog of cases. And a young reporter, William Longgood, had already written about their case for the New York World-Telegram and Sun, making her hopeful that other reporters would show up that day, too.

The morning began with Hinds’s opening statement. Spock listened to his familiar argument. He offered the court an analogy, invoking the national debate over prohibition. Never, he said, would anyone have suggested that alcohol consumption be compulsory. But the plaintiffs had been forced to consume DDT “against their will.” The government had also abused its authority by trespassing on private land and had caused “irreparable injury” in doing so. DDT surely had its advantages, he added, but they hadn’t been duly weighed against its harms.

DDT was not the problem, Baker argued; the problem was “reactionaries” fighting every new scientific advance from anesthetics to vaccines to X-rays.The defense, in response, pointed to a 1928 Supreme Court ruling that upheld the Cedar Rust Act of Virginia, affirming state authority to cut down trees on private property to prevent the plant disease’s spread. “We are not going further than that,” said Assistant US Attorney Lloyd H. Baker, representing the Department of Agriculture. Like cedar rust, the gypsy moth caterpillar was capable of causing “serious economic loss” on the order of “millions and millions of dollars,” Baker said.

DDT spraying had certainly killed birds, fish, and aquatic insects, he granted, but their populations had returned to normal within a few months. And the spraying may have forced people to consume DDT, but DDT was already widespread in the American diet. The average person in the US already had DDT in his or her fat, and government scientists had shown that this was harmless.

DDT was not the problem, Baker argued; the problem was “reactionaries” fighting every new scientific advance from anesthetics to vaccines to X-rays. “But science,” he told the court, “will not be stopped.”

Spock soon noticed, with disappointment, that no other reporters had shown up. Given the snow, it wasn’t terribly surprising. She spent the day taking her own detailed notes, a decision that would later nudge the course of history her way. But that day, all she thought of was CAMP, which had promised news of the trial to interested parties across the Northeast: home owners who had spoken out against gypsy moth spraying in Massachusetts and Vermont, her friends at Organic Gardening and Farming magazine in Pennsylvania, readers who had donated to their cause, and her farming mentor and fellow Steiner acolyte, Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, who ran a biodynamic farm in Chester, New York. Spock had a typewriter and a brand-new Thermo-Fax machine in her basement, and as she made her way home from court that evening, she made plans to head downstairs after dinner to type up the first edition of what she planned to call “Today in Court.”

Polly was feeling ill again when Spock got home, but she stopped Spock with some news. A literary agent named Marie Rodell had called the house. She represented the nature writer Rachel Carson. Spock knew and loved Carson’s work: her 1951 book, The Sea Around Us, and her more recent book, The Edge of the Sea, with its passages that captured with vivid brilliance the craggy coast of Maine, where Spock had spent her summers as a child. It seemed unfathomable that Carson had called Spock’s home. Rodell, Polly reported, had said that Carson was curious to learn more about their case and that she was especially interested in hearing about the specific evidence they had collected.

Spock’s heart leapt. She pored through her materials, selected a handful of articles and reports, and copied them on the Thermo-Fax. Then she sat down to compose a letter to Carson. “We have marshaled some pretty solid scientific men and data, and are feeling confident,” she wrote. But she wasn’t so naive as to assume the case would be open and shut. Never one to waste an opportunity, she asked whether Carson, as such a respected authority on wildlife, would be willing to serve as a witness to strengthen their case. “I think you know how grim this struggle with the US government and the whole chemical industry is bound to be,” she wrote. She sent off the packet and waited for a reply.

___________________________________

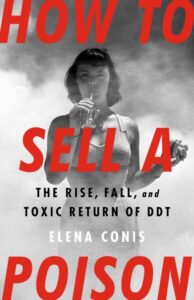

Excerpted and adapted from How to Sell a Poison: The Rise, Fall, and Toxic Return of DDT by Elena Conis. Copyright © 2022. Available from Bold Type Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group.