How a Dictionary Got Into the Marriage Equality Debate

And Why Lexicography Matters—Sometimes Too Much

It was Friday, morning-break time, and I was not just tired; I was beat, wiped, whipped, laid out, done in, dead. Usually during morning break, I got up for a bit of a stretch, walked around, refilled my coffee. I was working from home at the time and sometimes indulged in a little wander around my yard—a hard reset before I got back to work. Today, however, I had ignored the nice weather and instead put my head on my desk, forehead pressed to the Formica and arms covering my skull. I had joked with one of my yoga-loving co-workers that I was developing a series of poses we could do at our desks—a head-in-hands slump over galleys called Drudge’s Hunch, the arms-over-head seated stretch called Fluorescent Salutation, the hand-out position used to catch the fire door so it didn’t slam and bother everyone was Worrier’s Pose. My current pose was called Nuclear Fallout.

It had been two weeks of workplace hell. I was attempting some deep, yogic breaths (facedown on my desk—not the ideal position), intently listening to the sounds of my home office: the bone creak of the house corner being pushed by wind, the borborygmus1 rumble of a delivery truck idling outside, that goddamned mockingbird that had built a nest in the eaves right outside my office and was currently doing the Top 40 Birdcalls of North America on repeat. In a few minutes, I heard my email program bing, then bing again. I turned my head and peeped out from under my arm; Peter had sent me a link to a video, followed by about 15 exclamation points.

I ducked my head back under my arm and tried to be as Zen as possible, but curiosity got the better of me. I clicked the link and was taken to a clip from The Colbert Report. “Folks,” Colbert began, “turns out my old nemesis is back.” As he pulled a Collegiate up onto his desk, I maneuvered the mouse over to the pause button and jabbed violently. Noooooope, I thought, no, I can’t watch this. Not after the last two weeks. But the screen had frozen at an odd point, and I felt slightly uncomfortable staring at a grimacing Stephen Colbert. I relented. I slid my glasses up to the top of my head and rubbed my face vigorously. My forehead throbbed where I had been pressing it to my desk.

Colbert was finishing up a joke about “zymosan” when I focused on the screen again. He was saying that we had changed the definition of “marriage,” and added a new meaning: “the state of being united to a person of the same sex in a relationship like that of a traditional marriage.” This was true. “That means, gay marriage,” he explained. “I’m beginning to suspect that Merriam and Webster were conjugating more than just irregular verbs.”

I snickered. It had been the first honest laugh I’d had in a while.

The segment was only three minutes long, but I devoted the rest of my break to it, then wandered—a changed woman—out of my office and into the house. My husband was sitting at the dining room table, headphones on, scribbling out a horn arrangement. I stood next to him until I had his attention. I smiled incandescently, radiant; my face was damp with tears; the world smelled beatifically of roses. He raised an eyebrow in expectation.

“Welp,” I said, “I’ve made the big leagues. I’ve been parodied by Colbert.”

Lexicographers like to justify our existence by saying that words matter to people, and that the meaning of words matter to people, therefore lexicography matters. This is only a bit of a lie: if a word matters to a person, it’s most likely because of the thing that word describes and not because of the word itself. Sure, everyone has a word (or a handful of words) that they adore because they love the sound, the feel, the silliness or silkiness of the word; I defy anyone to say the word “hootamaganzy” aloud and not immediately fall in love with it, regardless of what it means.2 But scanning through the top lookups on any dictionary website shows that most words that interest us do so because we are unclear about the thing to which they are applied or we want to use the definition to run a litmus test on the situation, person, event, thing, or idea that that word was used of.

We know this bit of behavioral trivia not because this is innate knowledge lexicographers have about how people interact with their dictionaries but because of Internet comments. As dictionaries have moved online, lexicographers have developed a direct connection with users that they’ve never had before. The one thing that is most striking about all these comments—good, bad, ugly, and uglier—is that lots of people are really interacting with language in the etymological sense, expecting a mutual and reciprocal discourse from the dictionary definition.

“The general public—particularly in America—has been trained to think of the dictionary as an authority, and so what ‘the dictionary’ says matters.”

Lexicographers are the weirdos in the room: they’ll rhapsodize about the word itself, talk endlessly about the etymology or history of usage, give you weird facts about how Shakespeare or David Foster Wallace used the word. But ask them to comment on the thing that word represents, and they fidget. Ask them to do that with a word whose use and meaning describe systems, beliefs, and attitudes that have shaped Western culture, and they will do their damnedest to leave the room as quickly and quietly as possible.

The problem is not so much that lexicographers are objectively disordered when it comes to words (though they undeniably are). It is that the general public—particularly in America—has been trained to think of the dictionary as an authority, and so what “the dictionary” says matters. “The dictionary,” in a bid for cultural relevance and market share, is the one who has trained the public to think this way, but what we hold ourselves to be authorities on has changed dramatically since we started this gambit.

This has bitten us in the ass a few times.

In the late 1990s, we undertook a revision of the Collegiate Dictionary in which we added about 10,000 new entries. The new edition, the Eleventh, was released in 2003, and in an attempt to get people actually to buy dictionaries and not just talk about them, we highlighted some of the new entries in a marketing campaign and handed out “New Words Samplers” like candy at a parade. People wrote in for a few weeks asking about the new entries, and we had lively e-mail discussions with correspondents about “phat” (which, contrary to widespread belief, is not an acronym of “pretty hips and thighs” or “pretty hot and tempting”)3 and “dead-cat bounce” (which despite looking like a phrase is actually considered a word for entry purposes).4 But not all 10,000 new entries were highlighted; lots of new information lived in that dictionary for a long time before people found it.

One of the new additions was a second-level subsense—a sub-subsense—at the entry for “marriage” that was designed to cover uses of “marriage” that referred to same-sex marriage. We had hundreds of citations sitting in the files for this use, and more and more were coming in daily as states were debating the legality of gay marriage. The definition we settled on was “the state of being united to a person of the same sex in a relationship like that of a traditional marriage.”

Given the nature of the thing being described, we were very careful with how we defined that use of the word. We felt, reading through the citational evidence at the turn of the millennium, that it would be best to cover gay marriage in a separate subsense instead of broadening the existing definition of “marriage” (“the state of being united to a person of the opposite sex as husband or wife in a consensual and contractual relationship recognized by law”). The reasons straddled that line between the thingness and the wordness of “marriage” in ways that make lexicographers sink into Drudge’s Hunch. In 2000, while we were writing the Collegiate, the legality of same-sex marriage (the thing) was hotly debated; no state in the union had passed a law that allowed same-sex marriage, though several had challenged constitutional bans on same-sex marriage and one (Vermont) had passed a law allowing same-sex civil unions. Heterosexual marriage, however, was legal nationwide. So it’s not surprising, then, that the vast majority of our citations for the “romantic partnership” uses of the word “marriage” touched on the legality of the thing “marriage.” One thing being called “marriage” was legal, and another thing being called “marriage” was in a state of legal flux, but “marriage” was used to describe both things.

There was also a lexical marker that swayed us toward dividing this into two separate subsenses: “marriage” was increasingly used with modifiers to tell us what sort of marriage the writer was referring to. Prior to the 1990s, “marriage” was, relatively speaking, seldom modified by words like “gay,” “straight,” “heterosexual,” “homosexual,” or “same-sex.” But by 2000, all these words were common modifiers of the word “marriage”; by 2003, when the Eleventh Collegiate was released, “gay” and “same-sex” were the top two most frequently used modifiers of the word “marriage.” This signals two interesting (and seemingly contradictory) facts about the word “marriage”: that it was being used of a union between gay people, which accounts for the modifiers “gay,” “same-sex,” and “homosexual,” and that people were also seeking to differentiate between same-sex marriage and heterosexual marriage, which accounts for the use of modifiers like “heterosexual” and “straight.” If we had seen more use of the unmodified “marriage” of any committed couple, regardless of their genders, that would signal to us that the “gay” marriage sense and the “heterosexual” marriage sense were merging into one. Modifiers mark a philosophical—and, in this case, lexical—divide.

We were one of the last major dictionary makers to make this change to our dictionaries: the vagaries of dictionary production cycles meant that The American Heritage Dictionary and the Oxford English Dictionary both entered definitions or usage notes that covered same-sex marriage in 2000. The Oxford English Dictionary went with a usage note at its existing definition (“The condition of being a husband or wife; the relation between persons married to each other; matrimony”) that read, “The term is now sometimes used with reference to long-term relationships between partners of the same sex,” with a cross-reference to the entries for “gay.” The American Heritage Dictionary revised the first sense of its entry for “marriage” in 2000 to “A union between two persons having the customary but usually not the legal force of marriage,” and then in 2009 to “The legal union of a man and woman as husband and wife, and in some jurisdictions, between two persons of the same sex, usually entailing legal obligations of each person to the other.” Dictionary.com had also already entered a definition that covered the same-sex meaning: “a relationship in which two people have pledged themselves to each other in the manner of a husband and wife, without legal sanction: trial marriage; homosexual marriage.” Our decision was neither unique nor, in dictionary circles, controversial. It was boring, lexical. We gave it due thought, entered it, and moved on. The language is a big place: you can’t stop in one spot for too long. We moved ahead into the second half of the alphabet. The world, meanwhile, was spinning circles in court.

You cannot look at the evolution of the word “marriage” without looking also at the evolution of the thing itself. Though words have a life of their own, they are tethered to real-world events. Throughout the late 1990s, states began passing amendments to their own constitutions limiting marriage to a union between one man and one woman. In 1993, the Hawaiian Supreme Court ruled that denying marriage licenses to same-sex couples violated the equal protection clause of the Hawaii Constitution, which became the trigger for H.R. 3396—the bill known as the Defense of Marriage Act. By the time the Eleventh came out in July 2003, two states had already passed domestic partnership and civil union legislation, with one more soon to do it (Merriam-Webster’s home state, Massachusetts), and four states had, through judicial action or legislation, declared that marriage was restricted to one man and one woman. That left 43 states on the table. The War on Marriage was in full swing.

Not that we saw much of it in the dictionary offices. “We never heard a peep,” notes Steve Kleinedler. “Nothing. I kept expecting it, but . . .” He trails off, his hands opening into a shrug. A handful of questions about the new subsense began to trickle in to the Merriam-Webster editorial e-mail, but it was a literal handful, and they were mostly questions about when we updated the entry. A small grump of correspondents complained—but to be honest, fewer correspondents complained about the changes we made to the entry for “marriage” than complained about the inclusion of the word “phat” in the Eleventh Collegiate. The culture war seemed to have passed us by.

The operative word in that sentence is “seemed.”

On the morning of March 18, 2009, I padded into my home office with a large cup of coffee and booted up my work e-mail. I blew on my coffee while the e-mail loaded, then blew again; the e-mail was taking a very long time to load. When the program crashed, I groaned and took a huge, scalding gulp of coffee. An e-mail program crash could mean only one of two things: (1) the servers and building were on fire or flooded, or (2) there was a write-in campaign afoot. I rebooted my computer and fervently prayed for number 1 to be the case. My computer dinged to life, and the e-mail began downloading again, which meant the building was not on fire; I covered my face and mooed in despair. The resident mockingbird heard me and answered with a litany of birdsong.

Write-in campaigns are the inevitable product of a strong conviction that someone or something is wrong, a woefully misguided sense of grassroots justice, and unfettered Internet access. A person discovers an entry they don’t like in the dictionary, and they petition 900 of their closest friends to write to us and tell us to remove or revise that entry. Those 900 people then post the write-in request to their blogs or social media profiles, and then 900 of their closest friends write in about the word they want removed or revised. It’s like a perverse, linguistic pyramid scheme: everyone pays in a little and gets nothing in return except for the person at the top (me). I get a ton of e-mail to answer.

When the morning e-mail loaded, I saw why my computer had balked: sitting in my in-box were hundreds of e-mails, most of them with subject lines like “Definition of marriage” and “OUTRAGED!” While I scanned the numbers, my e-mail program binged again: 15 new e-mails in the last two minutes. I slunk into Drudge’s Hunch and wished for a swift and painless death.

The first thing an editor must do in the face of a write-in campaign is figure out where the e-mail is coming from. Fortunately, one of the first people to write in, frothing with rage, handily linked to one source of their displeasure: a story published on the conservative news site World Net Daily titled “Webster’s Dictionary Redefines ‘Marriage.’” The article began, “One of the nation’s most prominent dictionary companies has resolved the argument over whether the term ‘marriage’ should apply to same-sex duos or be reserved for the institution that has held families together for millennia: by simply writing a new definition.”

I carefully scooted my keyboard and coffee cup to one side and then placed my head on my desk and groaned. No, no, no: we were not involved in this cultural argument. Leave the dictionary be.

The article included a one-minute video that, from the get-go, makes it clear that this was not just about recording a word’s use for some folks. Over ominous music, the question appears: “What do you do if the dictionary does not support your definition of a word?” I knew where this was going—straight to Panictown. The video flashed some various definitions of “marriage” on-screen to make its point: that marriage has been described as “permanent” and between a man and a woman. Then it showed the new definition we had added in 2003, and suggested that we changed the definition of “marriage” because we didn’t agree with what the institution of marriage was: permanent and between one man and one woman. The definition faded to black, and the video ended with a giant “WAKE UP!” which grew until it swallowed the screen.

Reluctantly, I clicked back to the article. It went on to note that a dictionary from 1913 made no mention of same-sex marriage and, in fact, offered biblical support for marriage. At this, I began cackling, desperately. Of course one of our dictionaries from 19135 didn’t mention same-sex marriage: it wasn’t a common use of the word “marriage” back then! And of course it offered example sentences from the Bible. If you were literate in the United States during that time period, you were likely familiar with the Bible, because it was one of the few books that even the poorest families had on their shelves, and so was used didactically in educational settings.

The article claimed we refused to comment—“Hey, that’s a lie, I have to respond to everything that comes in!” I yelled at the computer—but noted that an editor denied any agenda to a World Net Daily reader.

Upon reading this, my stomach slid into my shoes and tried to hide under the desk. I bet I knew that editor:

“We often hear from people who believe that we are promoting—or perhaps failing to promote—a particular social or political agenda when we make choices about what words to include in the dictionary and how those words should be defined,” associate editor Kory Stamper wrote in response.

“We hear such criticism from all parts of the political spectrum. We’re genuinely sorry when an entry in—or an omission from—one of our dictionaries is found to be offensive or upsetting, but we can’t allow such considerations to deflect us from our primary job as lexicographers.”

Stamper justified the redefinition, too. “In recent years, this new sense of ‘marriage’ has appeared frequently and consistently throughout a broad spectrum of carefully edited publications, and is often used in phrases such as ‘same-sex marriage’ and ‘gay marriage’ by proponents and opponents alike. Its inclusion was a simple matter of providing our readers with accurate information about all of the word’s current uses,” Stamper wrote.

I took a deep breath, and began searching through my e-mail replies while half of my brain ran circles around my head, screaming in terror. I found the very lengthy response I had sent months earlier to a reader and compared it with what had been quoted in the article. Yes, that was exactly what I had written. They had quoted a big middle chunk of my reply without altering it. I exhaled, and only then did I realize I had been holding my breath.

I looked at the very first e-mail that came in after the article ran. It began, “Sirs: Your company decision to change the definition of the word ‘marriage’ to include same-sex perversion is an utter disgrace.” In the meantime, while I had been reading the article and watching the video, 50 more e-mails had come in. With an acid pit opening in my stomach, I decided to see who else was calling for God’s judgment on the dictionary. Time to go googling for controversy.

One of the first hits I turned up was from a web forum that quoted my very first correspondent, Hal Turner. He had a blog, where he had posted his response to us and encouraged all his listeners and readers to share their upset with us. Something scratched deep in my brain; I knew that name, where had I heard that name? I opened up a new browser window and searched for Hal Turner and discovered where I had heard that name before: I had read and marked an article in The Nation about him:

In 2003 Turner said US District Judge Joan Humphrey Lefkow was “worthy of being killed” for ruling against white supremacist leader Matthew Hale in a trademark dispute. The day after Lefkow’s husband and mother were found murdered on February 28, Turner penned an article for the far-right chat room Liberty Forum outlining tips to help white supremacists avoid scrutiny from federal agents. “So what can we, as White Nationalists (WN), expect as a result [of the killings]?” Turner wrote. “Frankly, a SHIT STORM!”

The rationalizing nerd part of my brain spoke up. But look, it reasoned, at least he didn’t advocate violence against dictionary editors, right?

I went back to the original browser window and clicked a link to the forum that had re-posted his blog post. There was a short inscription to introduce the re-post and set the tone for readers: “fucken [sic] gay homosexual pervert pedophile sodomizing faggot shit-eaters.” I shoved the keyboard aside and slid into Nuclear Fallout position.

After a few deep breaths, and bolstered by the decision that, come hell or high water, I was absolutely going to have two beers tonight, I closed out the hate forum and went back to the WND article to scan for comments. I caught the author’s last name and the silken thread of my sanity snapped cleanly. It was “Unruh,” which means “smooth” in Old English. Mr. Smooth.

I cackled for a long enough time that my husband set aside his work, came downstairs, and poked his head into my office. “Are you okay?”

“No,” I laughed, “no, I am not, and I will not be so for—” Here I looked at my e-mail and made a quick calculation on how long it would take me to answer all 500, nope, now 513 complaints about “marriage.” “I will not be okay for at least three days. Assuming nothing else comes in.” Two beats, then my e-mail binged obligingly, notifying me of new mail. Only the universe could have such impeccable comedic timing. I redoubled my laughter.

My husband furrowed his brow. “Hon . . .”

“Hey,” I said, suddenly serious, “you didn’t drink the last two beers in the fridge, did you?”

The complaints about this subsense of “marriage” came down ultimately to one common sore spot: gay marriage (the thing) was not legal or moral, and so our revisions to “marriage” (the word) were also not legal or moral. Enough people felt passionately about this that the defining batch I had been working on prior to March 18, 2009, ended up being three weeks late.

“Jerkery, like stupidity and death, is an ontological constant in our universe.

There’s certainly nothing wrong with feeling passionately about language; hell, if lexicographers feel passionate about anything, it is most certainly language. But people who start up and perpetuate write-in campaigns to the dictionary are usually grossly mistaken about what a change to the dictionary will actually accomplish. They believe that if we make a change to the dictionary, then we have made a change to the language, and if we make a change to the language, then we also make a change to the culture around that language. We see this most poignantly in requests to remove slurs of various kinds from our dictionaries. If you remove “retarded” from the dictionary, people tell us, then no one will smear someone as “retarded” ever again, because that word is no longer a word. I am the unfortunate drudge who must inform them that we cannot miraculously wipe out centuries of a word’s use merely by removing it from the dictionary.

To letter this sign with a slightly larger brush: removing a word from the dictionary doesn’t do away with the thing that word refers to specifically, or even tangentially. Removing racial slurs from the dictionary will not eliminate racism; removing “injustice” from the dictionary will not bring about justice. If it were really as easy as that, don’t you think we would have removed words like “murder” and “genocide” from the dictionary already? Jerkery, like stupidity and death, is an ontological constant in our universe.

It’s easy to scoff at that notion, but before you do, consider this: dictionary makers themselves are the ones who have created this monster.

The prevailing attitude toward words in the 19th century, you will remember, was that right thinking led to right usage, and right usage was a hallmark of right thinking. American lexicographers had, to a certain extent, bought into this notion. Even Uncle Noah gets into the act: he makes it clear in the preface to his 1828 dictionary that his work is a natural extension of American exceptionalism, the same doctrine by which the nation “commenced with civilization, with learning, with science, with constitutions of free government, and with that best gift of God to man, the christian religion.”6 But in the end, it wasn’t American exceptionalism that gave rise to the notion that the dictionary was an authority on language and life: it was marketing.

It begins, for Noah Webster and the American dictionary as an institution, with Joseph Worcester. Joseph Worcester was an American lexicographer and, to Noah’s mind, Webster’s protégé. He was one of the nameless assistants to Webster during the compilation of the 1828 and also produced his own abridgment of Johnson’s dictionary, supplemented with a popular pronouncing dictionary of the day. Webster hired Worcester to help him complete an abridgment of the 1828, knowing that he had to find a way to make money off his magnum opus. Worcester assisted him and then promptly released his own dictionary in 1830, A Comprehensive Pronouncing and Explanatory Dictionary of the English Language. Webster was livid—hadn’t he given Worcester his start?—and more to the point Worcester’s dictionary was suddenly in direct competition with Webster’s dictionaries to capture the hearts, minds, and (most important) extra cash of America’s schoolchildren and their families. Worcester’s more conservative approach to the language, which preserved more of the British spellings and pronunciations of words, earned him a number of fans.

And thus begins the Dictionary Wars of the 19th century. Webster went on the offensive with the best tool in the 19th-century marketer’s arsenal: the scalding anonymous letter to the editor. Webster (or someone representing his interests) started the volley with an anonymous letter published in the Worcester, Massachusetts, Palladium, in November 1834, accusing Worcester of plagiarism and implying that those who bought his dictionaries were not only getting an unoriginal work but also supporting a common thief and materially injuring an American patriot:

[Worcester] has since published a dictionary, which is a very close imitation of Webster’s; and which, we regret to learn, has been introduced into many of the primary schools of the country. We regret this, because the public, inadvertently, do an act of great injustice to a man who has rendered the country an invaluable service, and ought to recieve [sic] the full benefit of his labors.

Worcester defended himself, and the hostilities were on.

When George and Charles Merriam bought the rights to Webster’s dictionaries in 1844, they knew that they couldn’t continue to sell the dictionary at the price that Webster himself had sold it—20 dollars, exorbitant for the age.7 Their first order of business was to revise the 1841 edition of Noah’s AmericanDictionary into a single-volume dictionary that could be sold for six dollars—a sum that, while still a bit steep, was much more in line with what the average consumer could afford in the mid-19th century. The whole point of doing so was to keep up with Worcester. The sale of Webster’s work had been on the decline since Worcester had published his 1830 dictionary, and when Worcester came out with another dictionary in 1846, A Universal and Critical Dictionary of the English Language, all hope seemed lost.

The Merriams didn’t care about the Webster legacy. Market share was at stake, and so they resorted to the marketing tactics of the 19th century: hyperbole and smear.

The hyperbole begins as soon as the 1847 edition of A nAmerican Dictionary of the English Language is published. Advertisements placed in the Evening Post of New York give an extensive list of the new American Dictionary’s merits but end with this:

The work contains a larger amount of matter than any other volume ever published before in the country, and being the result of more than 30 years’ labor, by the author and editors, at the low price of $6, it is believed to be the largest, cheapest, and best work of the kind ever published.

By contrast, ads for Worcester’s 1846 Universal were staid and stately. No typography tricks, no bluster: just a lengthy explication on the goals and methods of the lexicographer, followed by a few encomiums and testimonials that appealed to the taste and judgment of the discerning reader. But these ads were few and far between. Most mentions of Worcester’s Universal in the papers of 1846–1848 were in ads placed by booksellers that often contain no more information than the title of the dictionary itself.

The Merriams, on the other hand, continued their lexicographical putsch. Ads full of interesting typography blared, “The largest, best, and cheapest DICTIONARY in the English language is, confessedly, WEBSTER’S.” Worcester’s publishers steadfastly refused to bow to the vulgarity of cheap advertising, while the Merriam brothers went bonkers for it. “Get the best!” ads in 1849 proclaimed and never really stopped.

Meanwhile, the race was afoot: Worcester was working on a new dictionary, and one of the higher-level editorial staff at the G. & C. Merriam Company heard it was going to have illustrations in it. The Merriams went into action: they slapped some illustrations in a slightly expanded reprint of the 1847, called it a “New Revised Edition” of Webster’s American Dictionary, and started the campaign blitz for its 1859 release all over again. Worcester released his massive dictionary, A Dictionary of the English Language,8 in 1860 to great acclaim, and his publishers had, in the years leading up to its release, tried to hop on the tagline train with “Wait, and get the best.” But by then, the Merriams had plastered their ads with interesting typography and illustrations all over the papers. “Get the best” was expanded to “Get the best. Get the handsomest. Get the cheapest. Get Webster.” And, as advertising is designed to do, vast claims were made about what owning one of these dictionaries would do for you: “A man who would know everything, or anything, as he ought to know, must own Webster’s large dictionary. It is a great light, and he that will not avail himself of it must walk in darkness.”

Combine all these things—the mudslinging and character assassination, the outsized commendations of each book, the claims about what owning one of these tomes will do for you—and you can see why the dictionary is considered not just an educational but a moral book in many people’s minds. Later dictionary marketing campaigns did nothing to discourage people from thinking this way. “The last 25 years have witnessed an amazing evolution in Man’s practical and cultural knowledge,” an ad for Webster’s Second New International claims in 1934. “No one can know, understand, and take part in the life of this new era without a source of information that is always ready to tell him what he needs to know.” Sales pamphlets for the Third didn’t tone down the grandiloquence, either: “Hold the English language in your two hands and you possess the proven key to knowledge, enjoyment, and success!” In 1961, Mario Pei, in reviewing the Third for The New York Times Book Review, finishes his review with “It is the closest we can get, in America, to the Voice of Authority.” A new marketing tagline was born: Merriam-Webster used “The Voice of Authority” in its marketing materials well into the 1990s.

It was the marketing and sale of the Third that made the connection between the dictionary, usage, and morality crystal clear.9 Reviewers of the Third threw up their hands in horror (often over things that were imagined) and declared that the English language as we knew it was finito. Critics called it “a scandal and a disaster” and “big, expensive, and ugly” and said that it was indicative of “a trend toward permissiveness, in the name of democracy, that is debasing our language.”10 But the criticism wasn’t just bell tolling for English: it was a warning that the Third marked a change in our way of living.

Jacques Barzun, a well-known writer and historian, ripped into the Third as a culture changer in his review of it for TheAmerican Scholar. “It is undoubtedly the longest political pamphlet ever put together by a party. Its 2662 large pages embody—and often preach by suggestion—a dogma that far transcends the limits of lexicography. I have called it a political dogma because it makes assumptions about the people and because it implies a particular view of social intercourse.” Evidence of that dogma? Entries that note that “disinterested” and “uninterested” are sometimes used synonymously, regardless of what usage commentators think. “The book is a faithful record of our emotional weaknesses and intellectual disarray,” Barzun concludes.

Pei began to have second thoughts about the Third in the summer of 1962 and wrote a piece for the Saturday Review in 1964 that was the culmination of those thoughts. It is a circumspect diatribe on Anglicized pronunciations, the peculiarities of in-house style sheets regarding punctuation and spelling, and the usual faffing about the labels “standard,” “nonstandard,” and “substandard.” But he frames the issue about a third of the way into his article: “There was far more to the controversy than met the eye, for the battle was not merely over language. It was over a whole philosophy of life.” The creation of The American Heritage Dictionary in the 1960s wasn’t just a linguistic response to the Third but a calculated cultural response to it. One ad for the first edition of The American Heritage Dictionary showed a long-haired young hippie; the ad copy read, “He doesn’t like your politics. Why should he like your dictionary?”

“Actual human lexicographers would rather hide under their desks than be reckoned culture makers.”

It is human nature to want to justify your own opinions by appealing to an external authority, and I can back that assertion up by eavesdropping: “my dad says,” “my priest told me,” “it’s the law,” “I read an article that says,” “doctors claim,” to infinity and beyond. It’s why advertisements tell you to “ask your doctor if ” their drug is right for you; it’s why teachers make students cite their sources when they write.

Dictionary companies had no problem setting themselves up as an authority on life, the universe, and everything throughout most of their history, because doing so ultimately sold books. Actual human lexicographers, on the other hand, would rather hide under their desks than be reckoned culture makers. In fact, and in spite of their publishing house’s own marketing copy, they have been deliberately avoiding the cultural fray since at least the mid-19th century. Noah Porter, the editor in chief for Webster’s 1864 American Dictionary of the English Language, sent notes to the staff warning against using quotations from antislavery sermons in the dictionary, because a reference book was not the place for them. Nonetheless, people still assumed that the dictionary was a cultural and political tool: an 1872 article in the McArthur, Ohio, Democratic Enquirer that compares the 1864 with previous editions actually asks, “Why does Dr. Porter ignore the Constitution of the United States?” Dr. Porter, it must be said, was merely writing a dictionary.

When I scanned the e-mail that had come in about the word “marriage,” it seemed like not much had changed in 137 years. We were accused of partisanship, of bowing to the “gay agenda,” of giving in to pressure to be politically correct instead of just plain correct, of abandoning common sense and Christian tradition. Noah Webster was turning in his grave with shame, I was told. People weren’t just angry; they were frothing mad. “You have crossed the line where you are irresponsible and attempting to pollute the minds of MY CHILDREN . . . BACK OFF!” one woman warned. I was invited to personally rot in hell no fewer than 13 times. I was told to get a life, get a fucking life, to fuck off and die, and also to swallow shards of glass mixed in acid. The e-mails were, almost to the letter, uninterested in actually knowing why we entered this new subsense of “marriage.” They didn’t care about the mechanics of language change; they cared about the mechanics of culture change. The existence of this definition was not merely recording a common use of “marriage” (the word); it was a declaration that same-sex marriage (the thing) was possible, and an engine by which same-sex marriage (the thing) would be firmly cemented in our society. Comments on Internet forums echoed the same thought. Jim Daly, the president of the Christian organization Focus on the Family, wrote a blog post highlighting the change to the definition. “The majority of voters in states across the U.S. have consistently rejected the idea of same-sex ‘marriage,’” Daly notes in a comment on the post. “As such, it could be argued that Merriam-Webster is shaping culture through their online dictionary.”

Our marketing director sent me a very quick note on the first day of the onslaught: set aside any e-mails that make actual threats against the company or my person. “Just in case,” she said. I forwarded her e-mail along to our senior publicist, Arthur Bicknell. “I’ve got a guy in here who is calling us all faggots and telling us we deserve to die. Is that actionable? And does this mean I finally qualify for hazard pay?”

Arthur and I had endured a number of write-in campaigns together—he called us Brother Perpetual Spin and Sister Accidental Scapegoat—but this one was particularly difficult. Every bit of spittle-flecked vitriol that he and I received on a daily basis was horrifying; we both felt dehumanized by it. The hateful comments weren’t just directed toward gay people. One e-mailer asked if the next thing we were going to legislate was letting different races marry (sorry, the Supreme Court actually beat us to that one, thanks for writing), and another’s e-mail handle was like a glossary of white nationalist tropes.

When you deal with that level of hatred and anger for weeks at a time, there are two paths of sanity open to you: quit your job, or crack jokes. I needed the money, so humor it was. I forwarded one e-mail to Arthur that read, in part, “Marriage is the union of one man and one woman. They are made to fit together and can serve no purpose other than to bring about Aids and spiritual death.” “And this is why you proofread your hate speech,” I commented. “REPENT OF YOUR HOMOSEXUAL MARRIAGE!” one e-mailer bellowed, and I forwarded it to my husband: “This is news to me, but okay: I repent.”

But the animosity and personal attacks meant the har-dee-har facade I had put up was prone to crumbling. The Sunday after the write-in campaign started, I was milling around after church when a friend approached to tell me she had seen my name in the news. I didn’t respond at all but tried to look nonchalant; I am sure that I looked ready to kick off my shoes and sprint away at the first sign of torches and pitchforks. The first day of the write-in campaign, my mother-in-law sent me an e-mail that began, “I was casually listening to the 700 Club,” and before I read any further, I closed out the e-mail, then the e-mail program, then my browser, and then stabbed at the computer’s power button until the screen went dark, just for good measure.11

Fortunately, it seemed like most of my correspondents were less interested in scaring the shit out of me and more interested in maintaining the sanctity of marriage. A large number of the cor- respondents in my in-box also mentioned that same-sex marriage (the thing) wasn’t legal in most states, and by entering this definition of “marriage” (the word), we were influencing the legality of same-sex marriage. It was clear that same-sex marriage cases were going to appear before the Supreme Court of the United States at some point in the future, and everyone knows that the members of the Court look at dictionaries when deciding a case.

They do, in fact—a study has shown that their use of dictionaries in deciding cases has increased through the Rehnquist and Roberts courts—but their use is inconsistent, prone to personal whims, and, most important, always secondary. A 2013 study analyzing the Court’s dictionary use in criminal, civil, and corporate law cases found that the justices tended to use dictionaries to bolster an opinion that was already held, rather than confirming the objective meaning of a word. The justices also tend to prefer certain dictionaries, some of which have been arguably out of date since 1934 and inarguably out of print since 1961:

During our 25 year period, the heaviest dictionary users in our dataset include Justices Scalia, Thomas, Breyer, Souter, and Alito. The dictionary profiles for these justices are individualized and distinctive. Justice Scalia opts more heavily for Webster’s Second NewInternational and the American Heritage Dictionary, general dictionaries that have been characterized as prescriptive in the lexicographic literature.12 Justice Thomas relies disproportionately on Black’s Law Dictionary. Justice Alito is partial to Webster’s Third New International and the Random House Dictionary, both regarded as descriptive. Justices Breyer and Souter are more eclectic: each is a frequent user of Black’s but Breyer also invokes Webster’s Third and the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) with some regularity while Souter turns more often to Webster’sSecond. Indeed, even the justices who make disproportionate use of one or two dictionaries are eclectic in that they frequently cite other dictionaries in particular cases. This pattern is consistent with a practice of seeking out definitions that fit a justice’s conception of what a word should mean rather than using dictionaries to determine that meaning.

The justices even joke about dictionaries while in session. In the oral argument for Taniguchi v. Kan Pacific Saipan Ltd., counsel for the petitioner notes that the defendant only appeals to one dictionary for a definition of “interpreter”—Webster’s Third:

JUSTICE SCALIA: Webster’s Third, as I recall, is the dictionary that defines “imply” to mean “infer”—

MR. FRIED: It does, Your Honor.

JUSTICE SCALIA:—and “infer” to mean “imply.” It’s not a very good dictionary. (Laughter)13

There are a number of pivotal court decisions regarding same-sex marriage in America, but four Supreme Court cases take center stage: Lawrence v. Texas (2003), which, while not ruling directly on gay marriage, set the stage by overturning state laws prohibiting sodomy in Texas (and, by extension, 13 other states); Hollingsworth v. Perry (2013), which upheld the Ninth District Court of Appeals ruling that overturned Proposition 8 (a California ballot measure and state amendment banning same-sex marriage); United States v. Windsor (2013), which held that the part of the Defense of Marriage Act that restricted “marriage” and “spouse” to heterosexual couples was unconstitutional under the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment; and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), in which the Court decided that the fundamental right to marriage for same-sex couples was guaranteed by both the due process clause and the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

All four cases were heard after changes to the definition of “marriage” were made to every major dictionary in use. In all four of the cases, in both oral arguments and written decisions (and dissents), a dictionary definition of “marriage” was only cited twice, in Obergefell v. Hodges. They appear in Chief Justice Roberts’s dissent in support of a restrictive definition of marriage (the thing, not the word); he cites Webster’s 1828 and Black’s Law Dictionary from 1891. Also cited are James Q. Wilson’s Marriage Problem, John Locke’s Second Treatise of Civil Government, William Blackstone’s Commentaries, David Forte’s Framers’ Idea of Marriage and Family, Joel Bishop’s Commentaries on the Law of Marriage and Divorce, Robina Quale’s History of Marriage Systems, and Cicero’s De Officiis (in translation). There are four written dissents; only Justice Roberts’s calls upon dictionary definitions.

If legislatures and courts are looking at dictionary definitions, it’s not the definitions that are swaying their opinions. To quote the 2013 study again, “The image of dictionary usage as heuristic and authoritative is little more than a mirage.” But try convincing people upset over the Court’s decision to redefine marriage that that’s the case.

Two weeks after the kerfuffle began, I sat at my desk, wheezing with much-needed laughter, as Stephen Colbert deftly skewered the whole write-in campaign. Every joke and punch line landed like a water balloon on a hot day. “The most sinister part is,” he continued, “Merriam-Webster made this change back in 2003.” Here I hollered at the screen—“Oh God, yes! Thank you!”—while he continued. “Which means that for the past six years of my marriage, I may have been gay-married and not known it.”

The floodgates opened and I sobbed with laughter, delighted that someone else was open throatedly mocking the whole situation. The little bits that I heard between my braying—calling us “same-sexicographers” who might “engayify” other straight words—were a balm unto Gilead, just the right response to two weeks of being told I was single-handedly bringing judgment down upon this great nation because I happened to answer an e-mail about the word “marriage.”

We continue to get a handful of e-mails complaining about the definition for “marriage” in the Collegiate, but around 2012 the substance of the complaints changed. Now we get just as many complaints that the two subsenses aren’t combined into one gender-neutral sense as we do that gay marriage is ruining America.

The definition, as of this writing, is still divided into those two subsenses. Language always lags behind life. Even after Obergefell v. Hodges, people still debate the dictionary definition of “marriage,” waiting for the Voice of Authority to prove them right once and for all.

Us “same-sexicographers,” however, have moved on. We’re well into the letter N at this point.

1. bor·bo·ryg·mus \ˌbȯr-bə-ˈrig-məs\ n, pl bor·bo·ryg·mi \-ˌmī\ : intestinal rumbling caused by moving gas (MWC11)

2. It’s another name for a hooded merganser. Don’t worry if you don’t know what a hooded merganser is, because that doesn’t detract from the wonder of “hootamaganzy.”

3. phat \ˈfat\ adj phat·ter; phat·test [probably alteration of 1fat] (1963) slang : highly attractive or gratifying : excellent < a phat beat moving through my body—Tara Roberts> (MWC11)

4. dead-cat bounce n [from the facetious notion that even a dead cat would bounce slightly if dropped from a sufficient height] (1985) : a brief and insignificant recovery (as of stock prices) after a steep decline (MWC11)

5. This dictionary, Webster’s Revised Unabridged, is actually a warmed-over version of Webster’s International Dictionary from 1890. The Revised Unabridged doesn’t cover a lot of modern linguistic territory, like “automobile” or “airplane,” and its definition of “Republican” mentions slavery and Lincoln.

6. The word “Christian” never appears with an initial capital in the entirety of the 1828. This is likely a holdover from Johnson’s styling of the word “Christian” in his dictionary (from which Webster “borrowed” liberally, ahem). Worcester capitalized “Christian” in his 1830 Comprehensive Pronouncing and Explanatory Dictionary of the English Language.

7. To give you a sense of how much money 20 dollars was in New England at that time, here is an ad from the January 11, 1829, Fitchburg (Mass.) Sentinel for W. M. Gray, a grocer on Main Street: “One Dollar will Buy 25 lbs. Rolled Oats or 10 Packages Rolled Avena, or 14 lbs. Nice Rice, or 25 Cakes Good Laundry Soap, or 12 lbs. Pure Lard, or 12 lbs. Salt Pork, or 15 lbs. Muscatel Raisins, or 30 lbs. Best Flour, or 2 gallons Best Molasses.”

8. It goes without saying that Worcester’s dictionary name was in homage to Johnson’s dictionary and a direct refutation of Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language—the name of the latter being equal parts homage and repudiation. Johnson fetishism runs deep in lexicography.

9. There are far better writers who have undertaken a full study of the production, sale, and fallout from the Third, and if the subject interests you, I would recommend you read those books (particularly Morton’s Story of “Webster’s Third” and Skinner’s Story of Ain’t) in addition to this one. Alas, I have but one book to write, and that book ain’t it.

10. Gil claims that no editors gave much credence to all this critical foofaraw. “Our problem was getting a Collegiate out, not worrying what some ignorant journalists thought.”

11. It turns out that she had heard a report about Finland and thought of me.

12. It makes perfect sense that Justice Scalia would have preferred The American Heritage Dictionary, because he was a member of its Usage Panel.

13. Not quite: The Third doesn’t say that “imply” and “infer” mean the same thing, though it does use the word “implication” in one definition of “infer” and “inference” at one definition of “imply.” The firewall between “imply” and “infer” is a fairly recent invention; the two words have had close meanings since at least the 17th century, when that slacker Shakespeare used “infer” to mean “imply” and vice versa.

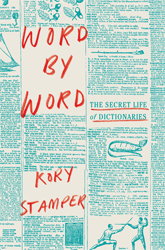

From Word by Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries. Used with permission of Pantheon. Copyright 2017 by Kory Stamper.

Kory Stamper

Kory Stamper is a lexicographer at Merriam-Webster, where she also writes, edits, and appears in the “Ask the Editor” video series. She blogs regularly on language and lexicography at her website, and her writing has appeared in The Guardian and The New York Times, and on Slate.com.