How a Democracy Descends Into Murderous Fascism: On Pinochet’s Chile

Philippe Sands Explores the Similarities Between Pinochet’s Military Junta and the Nazis

It was October 17, 1998, a Saturday afternoon, when I heard the news on the radio, waiting for the football results. It was my thirty-eighth birthday. The former Chilean dictator, General Augusto Pinochet, has been arrested in London, the BBC reported, at the request of a Spanish judge. This was interesting, as it wasn’t every day that a former head of state was detained. The details were sketchy, but it was said that the extradition request alleged crimes of genocide, torture and disappearances committed during his years in power, from the day of the Coup that brought him to power on September 11, 1973 until he stepped down, in March 1990.

News of the arrest gave rise to anger, delight and disbelief. The Chilean government protested that Pinochet was a former President and Senator-for-Life with complete immunity. “A transgression of international norms,” his son told a crowd throwing eggs at the British ambassador’s residence in Santiago. “An act of cowardice,” claimed the Pinochet Foundation, guardian of his legacy. “He was sleeping when police arrived at his room in the clinic.”

Pinochet’s opponents, on the other hand, were thrilled. Finally, he can be questioned on the fate of our loved ones, said the president of the Families of the Disappeared. A “unique opportunity” to answer for his regime’s human rights violations, said María Isabel Allende, daughter of President Salvador Allende, who died on the day of the Coup.

“An earthquake,” wrote Roberto Bolaño, a Chilean novelist living near Barcelona.

A matter for the courts, said the British government. “The idea that a brutal dictator should claim diplomatic immunity would be pretty gut-wrenching stuff” for most people, said Peter Mandelson, a minister.

Pinochet’s opponents, on the other hand, were thrilled. Finally, he can be questioned on the fate of our loved ones, said the president of the Families of the Disappeared.

Former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher declared the arrest to be outrageous, unlawful and inhumane, carried out “at dead of night” on a sedated Pinochet. It put all former leaders at risk, inhibiting decisions that might cause a leader to “appear before a foreign court to answer for it.” Those who wield “absolute power” would be less likely to relinquish it, “for fear of ending their days in a Spanish prison.” She was supported by Norman Lamont, a former Conservative minister who considered Pinochet to be a “good, brave and honorable soldier.”

I was a teenager at the time of the Coup and knew little about Pinochet. Over the next years, I didn’t visit Chile and the Chileans I came to know were mainly law students who took my classes, or academics exiled to Europe. I did, however, read books and see films about those times. In 1991 I saw a performance of Ariel Dorfman’s play Death and the Maiden at the Royal Court Theatre in London and I have not forgotten Juliet Stevenson’s portrayal of a woman who recognises her torturer, a memory she describes to her husband:

“Weren’t you blindfolded and sick?” [says the husband]

“I can be sick and recognise a voice.”

“A vague memory of someone’s voice is not proof of anything.”

“It’s his voice. I recognised it as soon as he came in here last night.

The way he laughs. Certain phrases he uses.”

Around that time I came to know a Chilean law professor, Francisco Orrego Vicuña, with whom I later worked on environmental issues. I was not aware he’d served as Pinochet’s ambassador in London, until that detail emerged and scuppered his election to become a judge at the International Court of Justice. He was in decent company: the writer Jorge Luis Borges was said to have lost his chance of a Nobel Prize for Literature because of the admiration he expressed for Pinochet.

Augusto Pinochet Ugarte was born in 1915 in Valparaíso, of Breton and Basque heritage. He joined the military and made his way up through the ranks. On the way, he taught in military academies in Chile and Ecuador, where he lived in the mid-1950s with his wife Lucía Hiriart. In 1970, Salvador Allende, the newly elected socialist President, appointed Pinochet as General Chief of Staff of the Army, serving under Carlos Prats, his friend and Commander-in-Chief.

For four years the DINA detained, interrogated and tortured tens of thousands of Pinochet’s opponents.

On August 23 1973, after Prats resigned, Allende promoted Pinochet to Commander-in-Chief. Eighteen days later, on September 11, Pinochet played a leading role in the Coup that toppled Allende, who committed suicide in the Moneda Palace, the home of the presidency. The events are portrayed in Patricio Guzmán’s The Battle of Chile, a trilogy of remarkable documentary films.

Pinochet, a virulent anti-communist and Germanophile, was anointed as head of a four-man Military Junta, and later President of Chile. He was supported by large sections of the Chilean population and, in the United States, by President Nixon and Henry Kissinger, who became Secretary of State a week after the Coup. They welcomed Pinochet’s government as a bulwark against Soviet influence and a means to promote free-market principles inspired by the ideas of the economist Milton Friedman and the “Chicago Boys.”

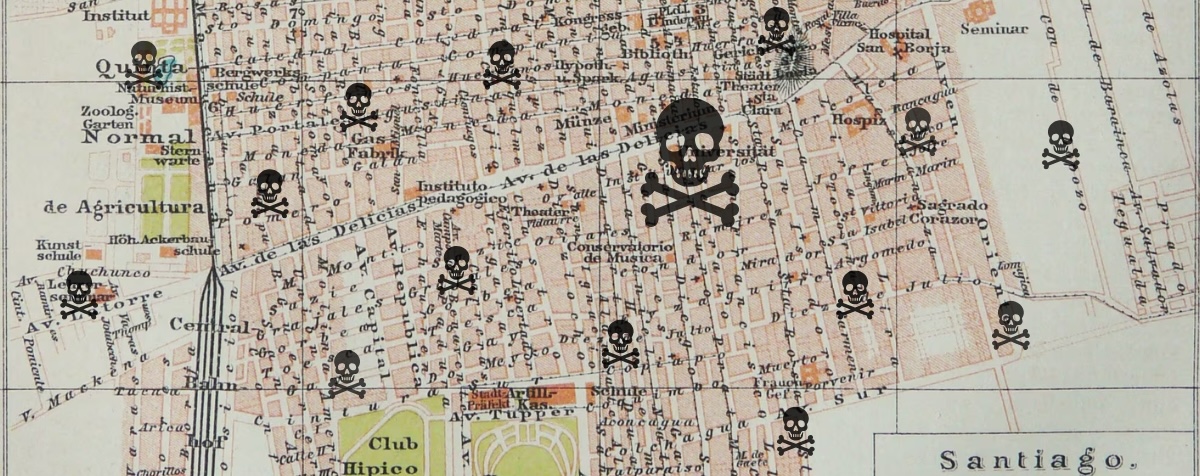

The Junta legislated to “remove Marxism from Chile,” dissolving leftist political parties and expropriating their assets. The Socialist Party building at Londres 38, in the heart of Santiago, was acquired and turned into a secret interrogation and torture centre, known as the Yucatán Barracks. Here, to avoid drawing attention, interrogators and guards dressed as civilians, uniformed personnel were prohibited and unmarked vans and other regular vehicles moved prisoners in and out. The Junta took over private companies to operate and finance its secret activities and repression.

The Junta established a secret police force, the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional, the DINA, to rein in opponents and run Londres 38 and other such places of torture and killing. As director, Pinochet appointed Manuel Contreras, a trusted Army man from the School of Engineers in Tejas Verdes near San Antonio, west of Santiago on the Pacific coast, giving him unlimited powers to destroy leftists. Every morning, Contreras reported to Pinochet who, he claimed, personally approved each DINA operation. Pinochet himself was protected by the boinas negras, the black berets, an elite military group.

For four years the DINA detained, interrogated and tortured tens of thousands of Pinochet’s opponents. Many were killed, and by September 1977, when the DINA was dissolved, more than fifteen hundred people had disappeared. Imprisonment and assassination became routine in Chile, and also abroad. “A country occupied by the dictatorship, which was directly in line with the thinking of the Nazis,” thought the poet Raúl Zurita.

Within a day of the Coup, Salvador Allende’s former ministers were sent to a newly constructed concentration camp on Dawson Island, in the Straits of Magellan, near Punta Arenas, in the south of the country.

Within a month, a Chilean Army death squad was engaged in a countrywide tour of assassinations. Ninety-seven people were killed in the operation that came to be known as the “Caravan of Death.”

Within a year, the DINA was operating dozens of detention centers. At Londres 38, on average one prisoner disappeared every day. Nearby detention centers included the National Stadium; the Villa Grimaldi; the clandestine cells at Cuatro Álamos, part of the regular facilities at Tres Álamos; and the secret Simón Bolívar Barracks, operated by the DINA’s Lautaro Brigade. The DINA acquired a house on the Vía Naranja, in a wealthy suburb of Santiago, where chemists produced sarin gas in the basement as literary salons were held on the upper floor.

The Rettig Report found that Pinochet’s leadership caused over 40,000 people to be illegally detained or tortured, and more than 3,000 to be murdered or disappeared.

The DINA operated centers around the entire country. In San Antonio there was the Tejas Verdes barracks and a little further south the torture facilities at Santo Domingo. In the far south, in Punta Arenas, the Old Naval Hospital was taken over and came to be known as the “Palacio de las Sonrisas” (“Palace of Smiles”).

A year after the Coup, the Pinochet government and the DINA acted to commit murder outside Chile. In September 1974, General Prats was assassinated in Buenos Aires. A “most capable man,” said Pinochet on hearing about the death of his old friend and predecessor as Commander-in-Chief. “I always felt affection for him.”

In October 1975, the exiled Christian Democrat leader Bernardo Leighton was the target of a failed assassination attempt, in Rome. In November 1975, on Pinochet’s sixtieth birthday, the DINA established Operation Condor, a joint project with Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay. It would target leftist leaders and democrats across South America.

In July 1976, Carmelo Soria, a United Nations official with full immunity under international law, was abducted on a central Santiago street. Two days later, the body of the dual Chilean and Spanish national was found in the city’s Canal del Carmen.

In September 1976, Orlando Letelier, Allende’s former ambassador to the United States and then Minister of Defence, was assassinated in downtown Washington, D.C.

On it went, for years, generating opposition. In September 1986, Pinochet’s motorcade was ambushed and five soldiers were killed and many others injured. The President, who narrowly avoided death, ordered a series of reprisal killings.

Two years later, in October 1988, Chileans voted “No” in a referendum that Pinochet organised to continue as President. Instead, they voted for a return to democratic rule, and in March 1990, after seventeen years in power, Pinochet stepped down, staying on as Commander-in-Chief of the Army.

A democratically elected government took office, a coalition known as the Concertación, supported by Christian Democrats and Socialists. President Patricio Aylwin established a National Com mission for Truth and Reconciliation, chaired by Raul Rettig, which reported in 1991. The Rettig Report found that Pinochet’s leadership caused over 40,000 people to be illegally detained or tortured, and more than 3,000 to be murdered or disappeared. Many put the numbers even higher.

In March 1998, Pinochet stepped down as Commander-in-Chief of the Army. He accepted the appointment of Senator-for-Life, which gave him complete immunity, as a parliamentarian, from legal proceedings in Chile.

By now, however, the cases in relation to the crimes of his government, and his own role, were stacking up. By October 1998, Juan Guzmán, a prosecutor in Santiago, was investigating Pinochet’s personal role in allegedly authorizing the “Caravan of Death” operation. As with other investigations, it could not proceed to trial, because the Amnesty Law signed by Pinochet in 1978 precluded almost all prosecutions and trials for the crimes committed by the government he headed over seventeen years.

The truth is that Pinochet felt himself to be above the law, and he had no regrets about his actions.

This was how things stood in Chile when Pinochet flew to London, a city he loved and where he felt himself to be welcomed, not least for his role in assisting the British in the Falklands/Malvinas war with Argentina, back in 1982.

The truth is that Pinochet felt himself to be above the law, and he had no regrets about his actions. I am a soldier, he liked to say, my Coup saved Chile from communism, leftist agitators and a Cuban future. In terms of style, he was not an intellectual or a thinker—unlike Carlos Prats, whom he feared for that reason—but something of a fox.

He liked Star Wars films and books about Napoleon Bonaparte, and enjoyed the company of military veterans, especially if they were old Nazis like Hans-Ulrich Rudel. “Hitler’s only mistake was to lose the war,” the Luftwaffe ace once told him. Pinochet admired his anti-communist stance, and was skeptical about the extent of Nazi crimes. He once asked a visiting West German government minister whether he was sure that six million Jews had really died. Wasn’t it only four million?

Pinochet was proud of his personal library, with books on guerrilla insurgencies, the writings of Antonio Gramsci and other Marxist theorists, and accounts of communist crimes. He had an original copy of the sixteenth-century epic poem La Araucana, written by the Spanish soldier and poet Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga, and was seemingly untroubled by its lyrical account of colonial Spain’s brutal response to the insurrection of Araucanian Indians in Chile. “Brute, unparalleled malevolence has polluted our invasion,” the poet recorded.

Pinochet’s appreciation of literature and brutality did not extend to lawyers, who made him wary. He appointed judges who would look after him, and lawyers who could protect him. He passed a law to immunize himself from risks of prosecution; the 1978 Amnesty Law gave him total protection.

The Amnesty Law, prompted by the notorious Hornos de Lonquén case, followed Pinochet’s decision to have Orlando Letelier killed in Washington two years earlier. This was a story I knew something about, as my father-in-law, André Schiffrin, published an account, Assassination on Embassy Row, and he and Letelier had been working on a book proposal at the time of his murder. “Letelier came for lunch, a few days before the assassination,” my wife Natalia once told me. “He said I had lovely freckles, a twelve-year-old girl remembers things like that.”

Letelier was murdered two months after US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger visited Pinochet in Chile, to offer support to the regime. Jimmy Carter had just won the Ohio Democratic primary, and Paul McCartney and Wings topped the music charts with “Silly Love Songs.” The Kissinger visit coincided with the ending of the ban on political parties in Spain, imposed in 1939 after General Franco’s Nationalists prevailed in the Spanish Civil War. Pinochet greatly admired Franco, who died a few months before Kissinger’s visit, and was one of the few foreign leaders to attend the funeral.

During their June 1976 meeting at La Moneda, Pinochet and Kissinger worried that communism was “springing up” again in Spain, and agreed that Chile’s Coup was merely a “further stage” of the conflict that caused the Spanish Civil War. I am “very sympathetic” to your efforts in Chile, Kissinger assured Pinochet. “We wish your government well,” the official transcript recorded.

Kissinger spoke the words in full knowledge of the massive human rights abuses being perpetrated in Chile, and efforts in the US Congress to block arms sales to that country. I want progress on human rights, he said, including constitutional limits on unlawful detentions. Only four hundred are still detained, Pinochet assured him, which wasn’t true, but Kissinger seemed uninterested in the numbers. “You did a great service to the West in overthrowing Allende.”

__________________________________

From 38 Londres Street: On Impunity, Pinochet in England, and a Nazi in Patagonia. Used with the permission of the publisher, Knopf, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2025 by Philippe Sands.

Philippe Sands

Philippe Sands is professor of law at University College London and visiting professor at Harvard Law School, and a barrister who litigates cases on international law around the world. 38 Londres Street is the third volume in a trilogy that began with the Baillie Gifford Prize-winner East West Street: On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity (2016) and was followed by The Ratline (2020). He lives in London, England.