How a “Centuries-Old” Carpet Duped Art Dealers and Curators For Decades

Dorothy Armstrong Explores the History of Real and Fake Antique Textiles, from Central Asia to Europe

On the morning of November 7, 1933, a Viennese art-dealer named Paul Perlefter left his lodgings in the luxurious Park Lane Hotel, London with a rolled-up carpet under his arm. At around 117 inches long and 75 inches wide when unfurled, it made a compact package. Perlefter was on his way to the V&A Museum to see its curator of textiles, Cecil Tattersall.

What Perlefter showed Tattersall excited the curator so much that he wrote that same afternoon to the V&A’s Deputy Keeper of Textiles, A.B. Wace, urging the museum to buy the carpet. Within two days the request had made it to the desk of the V&A’s director, Eric Maclagan. As soon as he viewed the item, Maclagan approved the purchase. Whereas most acquisitions were ponderous affairs, this one took little more than a week from beginning to end.

The V&A paid Perlefter £310, the equivalent today of £8,000, just over $10,000. This was 25 per cent of the V&A’s entire acquisition budget for that year. In their correspondence, Wace and Maclagan acknowledged the V&A’s “depleted funds”—the Great Depression had put it under severe pressure—but asserted their conviction that the cost was justified even “in the present state of affairs.”

For thirty years, Perlefter’s carpet hung peacefully on the wall in the museum, delighting visitors with its beauty, its unusual palette, enigmatic motifs and its echoes of four empires.

This highly desired carpet was ivory, with a distinctive repeated pattern of three circles organized into a pyramid and underscored by two wavy lines, forming regular rows marching across the entire field of the carpet. The motifs and borders were knotted in red, blue, black and other shades of cream or natural wool. Carpets of this type are believed to have originated in western Anatolia in the sixteenth century. Contemporaneous Ottoman price registers record similar white-ground carpets with spots and stripes as “Selendi” type, suggesting that they may have originated in the village of that name, west of the great carpet-making center of Ushak.

To those with a taste for the esoteric, they have much to recommend them. Only around thirty are still in existence, and it is likely they were always a small-scale specialized production. Aesthetically, they are completely unlike the richly colored and busy designs of other carpets from Anatolia, offering instead a serene, pale minimalism. Their signature three-circle motif floating on a pale sea invites questions and provokes fantasies. Speculation on the history and meaning of the motif offered what has been described as “a boon for rug dealers and authors on the lookout for a lurid sales pitch.”

These spots and stripes were a favored motif of Ottoman makers and merchants, with objects bearing the design traded across the empire’s growing territory throughout the sixteenth century. It can be found on tiles from the peak of Ottoman ceramic production in İznik and woven into velvet and brocade for splendid royal kaftans. Theories abound. Some modern commentators suggest that the circles represent the triple role of Ottoman sultans as chieftain, warrior and emperor. Others see the three circles and two wavy lines as a symbol of the three continents and two seas ruled by the sultans—Europe, Asia and Africa, and the Mediterranean and the Black Seas.

But the symbol had been in use across Asia for centuries before the white-ground rugs from Anatolia were woven, and indeed long before the Ottoman Empire itself. In 1902, the scholar Wilhelm Bode suggested that it derived from an older Buddhist symbol of three jewels surrounded by fire. Bode interpreted the three circles as the Buddhist magic gems which can fulfill all material and spiritual desires, and the two wavy lines as a stylized version of the flames. He gave the motif a Sanskrit name: tschintamani, wish-fulfilling jewels. Carpets which bear it are known as chintamani to this day.

Other scholars looked to Iranian and Central Asian folklore for the meaning of the motifs, proposing that the spots and stripes might be intended to evoke the leopard and tiger skins worn by ancient warriors in those cultures. Rustam, the hero of the eleventh-century Iranian epic Shanama: The Book of Kings, famously wore a tiger-skin jerkin. The gigantic red-haired warrior fought the seven-headed White Div to save his shah, Kay Kāvus, who had been captured and blinded by the demon chieftain. Rustam needed to cut out the Div’s liver so that he could burn it and smear the ashes on Kay Kāvus’s eyes to restore his sight. In the many gloriously illustrated versions of this episode of the Shanama, Rustam is shown wearing his tiger-skin jerkin, sometimes complete with its claws.

By the time Tattersall and Wace set about making their case for acquisition in 1933, a wealth of intriguing stories were available about the meaning of the motifs in the carpet. And yet the two curators did not evoke Buddhist monks, legendary Persian heroes or even mighty Ottoman emperors to ignite the imagination of the V&A’s budget-holders. Instead they turned to Central Asia.

The Turco-Mongol emperor Timur Leng, known to the West as Tamerlane, was a monumentally successful nomadic leader, renowned and feared in late-medieval Europe. Said to be descended from Mongol emperor Chinggis (Genghis) Khan, Timur forged a vast empire across Asia in the fourteenth century. The chintamani motif has been found on coins minted in his name, and Ruy González de Clavijo, who met Timur as Henry III of Castile’s ambassador to Samarkand, believed it to symbolize the ruler’s three territories: Persia, Central Asia and India. It is said that Timur celebrated the 1366 conquest of Samarkand by dipping his fingers into the blood of an enemy corpse and printing three red circles on the door of a mosque.

Here was a seductive pitch for Perlefter’s carpet. Tattersall and Wace immediately began describing it as a carpet bearing the “badge of Tamburlaine” in their correspondence with V&A director Maclagan, despite believing that it was made in sixteenth-century Anatolia, three hundred years after Timur, two thousand miles from Samarkand and under a different empire. The curators were of course mindful that the motif had also been used by the Ottomans, but this was manifestly not an Ottoman court carpet—and so Timur offered a useful imperial alternative.

Furthermore, the Central Asian heartlands that Timur had once ruled were a very present concern in 1930s Britain. British India faced Soviet Central Asia across the Wakhan Corridor, a strip of Afghanistan only eleven miles wide at its narrowest points, which in 1893 had been designated the buffer zone between the Russian and British Empires. The fathers and grandfathers of the curators of Britain’s leading museums had spent the previous century anxiously watching the Afghan frontier as imperial Russia expanded into what had long ago been Timurid territory. There were Maclagans in the British government in Punjab in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

For thirty years, Perlefter’s carpet hung peacefully on the wall in the museum, delighting visitors with its beauty, its unusual palette, enigmatic motifs and its echoes of four empires.

And then, one day in March 1962, George Wingfield Digby, Keeper of Textiles at the V&A, received a letter from one Nessim Cohen. An art-dealer and carpet specialist in the US, Mr. Cohen believed that, far from being centuries old, the V&A’s Schwarzenberg chintamani had in fact been woven mere decades ago. Curators often receive information from the public suggesting alternative histories for objects in a museum’s care, and at first Mr. Cohen was rebuffed as just another amateur enthusiast. But he refused to let the matter go, continuing to write to the museum every six months for two years. “I am a little puzzled,” Digby wrote, “at Mr Cohen’s extraordinary persistence.”

Digby turned to (who else) May Beattie. Her suspicions were alerted from the start. Her analysis sheet notes that among the “yellow/camel” wool of the lengthwise warp (the yarns which are strung on the loom as the first step of constructing a carpet), there were three stripes of red. This looked to Beattie “like aniline”—the family of synthetic dyes that had only entered large-scale carpet production in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Demand for luxury objects exploded in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries….As prices soared, scammers and fraudsters got in on the action.

When the red warp dye was chemically analyzed in 1964, it was found to be a mixture of purpurin, first produced in 1867, and chrysophenine, first synthesized in 1885. The aniline-dyed threads were part of the foundational structure of the carpet; there was no possibility of them having been added as part of a repair. The carpet had to have been made after 1885 rather than in the sixteenth century. Beattie amended her analysis sheet to record this, unusually for her, in red ink. The carpet was quietly withdrawn from the gallery and placed in storage.

Badly stung, it wasn’t long before Digby’s ire extended to the messenger who first alerted him to Perlefter’s deception: Nessim Cohen. As he faced down embarrassing publicity in the international press, Digby wrote to a fellow V&A official in a barely legible scrawl of angst, “This is clever advertising for the dealer and ‘expert’ Nessim Cohen! […] I wonder if he doesn’t know too much about this and other of Perlefter’s carpets.”

As with all good conspiracy theories, the story of Perlefter and Cohen would soon become associated with other nefarious activities. On 2 January 1964, Digby was contacted by Labour Member of Parliament Tom Driberg, later Baron Bradwell. Driberg had long been suspected, without confirmation, of being part of the Soviet spy ring that included Kim Philby and Guy Burgess. He had louche tastes. As a young man he had been a close friend of necromancer Aleister Crowley, and in the early 1960s included in his social circle both the Rolling Stones and the East End gangsters the Kray twins. He was also connected to Nessim Cohen, and had learned of the scandal of the faked carpet through that connection. In early 1964 he sought more information from Digby, for now lost and unknown purposes. He was an inveterate collector of gossip, so maybe it was just lust to know secrets; but, given his connections with the criminal underworld, perhaps he was checking that he himself wasn’t somehow exposed in the story.

Demand for luxury objects exploded in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, driven by private collectors who had amassed huge wealth in the Industrial Revolution and by public museums established to celebrate and preserve the spoils of empire. As prices soared, scammers and fraudsters got in on the action.

__________________________________

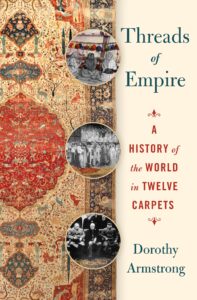

From Threads of Empire: A History of the World in Twelve Carpets by Dorothy Armstrong. Copyright © 2025. Available from St. Martin’s Press, an imprint of Macmillan.

Dorothy Armstrong

Dr. Dorothy Armstrong is a historian of the material culture of South, Central and West Asia, and for the last decade has tried to penetrate the mysteries of Asian rugs. She has published, podcast and lectured widely on carpets. She was tutor at the Royal College of Art and Edinburgh College of Art, and from 2021 has been the Beattie Fellow in Carpet Studies at the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. She is an avid collector of carpets and is as a result also an expert on clothes moths.