How 11 Writers Organize Their Personal Libraries

You can't put Pynchon next to Plato (Unless They're Both Pink)

There’s a secret war raging on the internet. The stakes are high. The warriors are fierce. The battleground is your bookshelf. Do you alphabetize? Do you color-code? Do you have no system at all? You’ll have to pick a side. Obviously I’m joking, but let’s face it: if you’re reading this space, you probably have some opinions about the best way to arrange your books. You’ve also probably snooped in someone else’s personal library. After all, as Jeanette Winterson once said, “when we go to somebody’s house, what’s better than looking at their bookshelves? Nobody’s ever going to say, “Can I see the index to your Kindle?” It’s so depressing and so unsexy.” A person’s bookshelves can tell you a lot about them—their interests, their histories, their dusting abilities—and while the content is what’s most important, of course, the organization can also speak volumes. (Sorry.) Of course, I always find it particularly interesting to find out how voracious readers (and often this means writers) organize—or once organized—their bookshelves, and so to that end, I’ve tracked down the systems, current and former, of a few notable literary figures below. If it inspires you to spend an evening taking all of your books off the bookshelves and putting them back on again, well, you’re welcome.

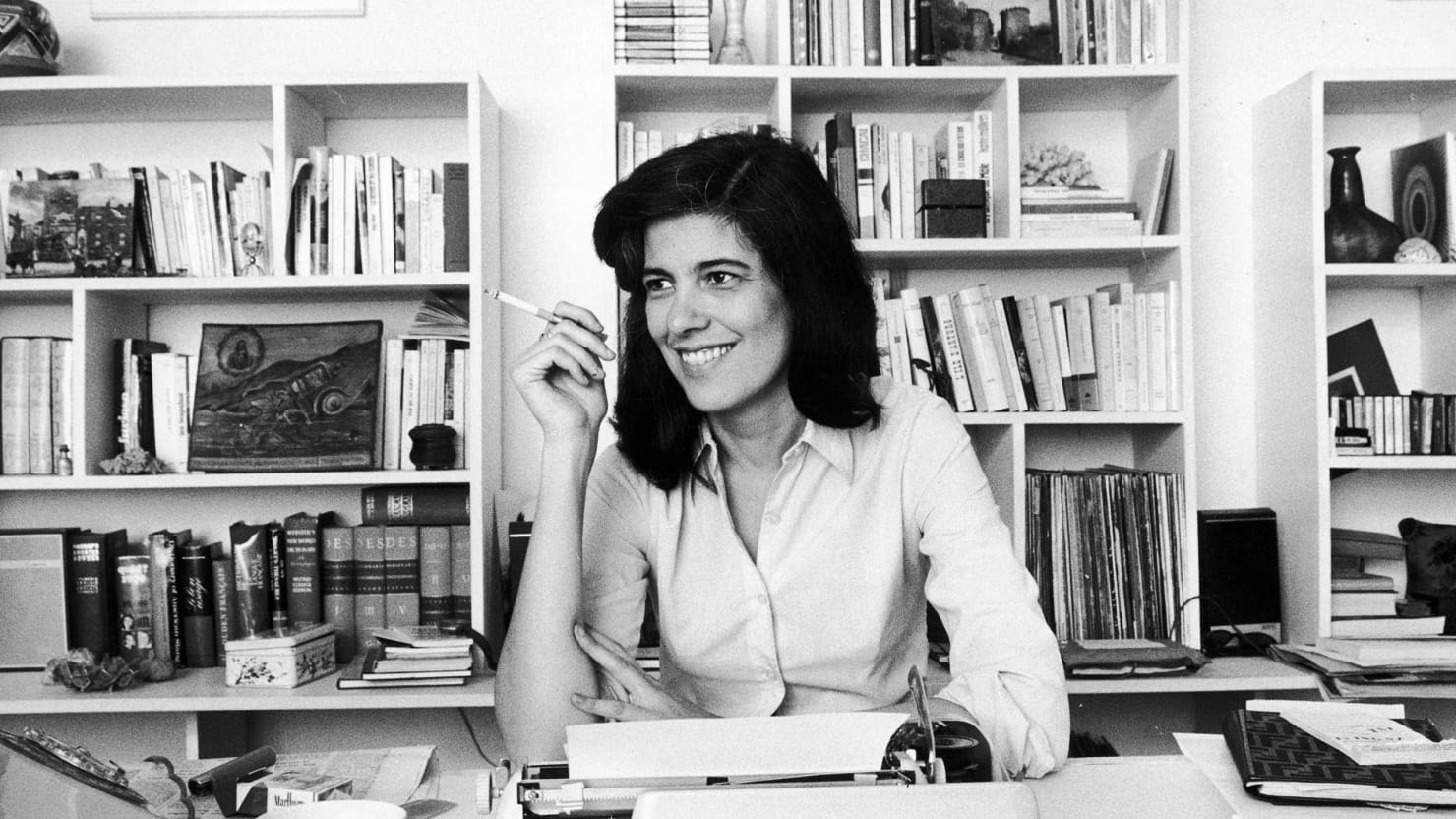

Susan Sontag at her desk.

Susan Sontag at her desk.

Susan Sontag arranged her books “by subject or, in the case of literature, by language and chronologically. The Beowulf to Virginia Woolf principle.” But never alphabetically. “I know people who have a lot of books,” she told Leslie Garis for The New York Times in 1992. “Richard Howard, for instance. He does his books alphabetically, and that sets my teeth on edge. I couldn’t put Pynchon next to Plato! It doesn’t make sense.” Instead, Sontag has a section for English literature (“You need a ladder. It starts here, and here are the Chaucerians . . . and then comes Shakespeare, Elizabethan Stuart plays, Marlowe, Middleton, Webster, the poets . . . It’s very approximate. Here’s Beckford, William Blake and then Wordsworth. . . Here’s Byron. I have all of English literature here. There’s Oscar Wilde, and there’s Meredith and Hardy. Of course, when I get into the modern stuff you can see who I read and who I don’t. For instance, I adore V. S. Naipaul.”), then Spanish, Italian, Japanese, Greek, Chinese and Russian, “ancient history, Judaism, a huge library of early Christianity, followed by Byzantium and the Middle Ages . . . philosophy, psychiatry and the history of medicine.” Her own books she tucks into a tiny room so she doesn’t have to look at them.

Yanagihara’s apartment. Photo: Sze Tsung Leong

Yanagihara’s apartment. Photo: Sze Tsung Leong

Hanya Yanagihara keeps some 12,000 books in her Manhattan apartment. She arranges them alphabetically, of course. “Anyone who arranges their books by color doesn’t truly care what’s in the books,” she told The Guardian. “I’ve always had them and collected them. I have multiple editions of certain titles so I can give them away. But I do try to do a big cull every few years.”

Ayelet Waldman and Michael Chabon. Photo: Aya Brackett

Ayelet Waldman and Michael Chabon. Photo: Aya Brackett

On the other hand, it’s probably safe to say that Ayelet Waldman and Michael Chabon care what’s in the books. “Not long ago,” Waldman told The New York Times, “my husband decided in a fit of who knows what lunatic O.C.D. to organize the books in our summer house by color, an odd move when you consider that both our sons are colorblind. The result has been that between the months of June and August, I have no idea where anything is, and am forced to just buy a second copy of any book I want to reread. A tip for book jacket designers looking to stand out: There are very few purple book jackets out there. Black, on the other hand, is sadly overused.”

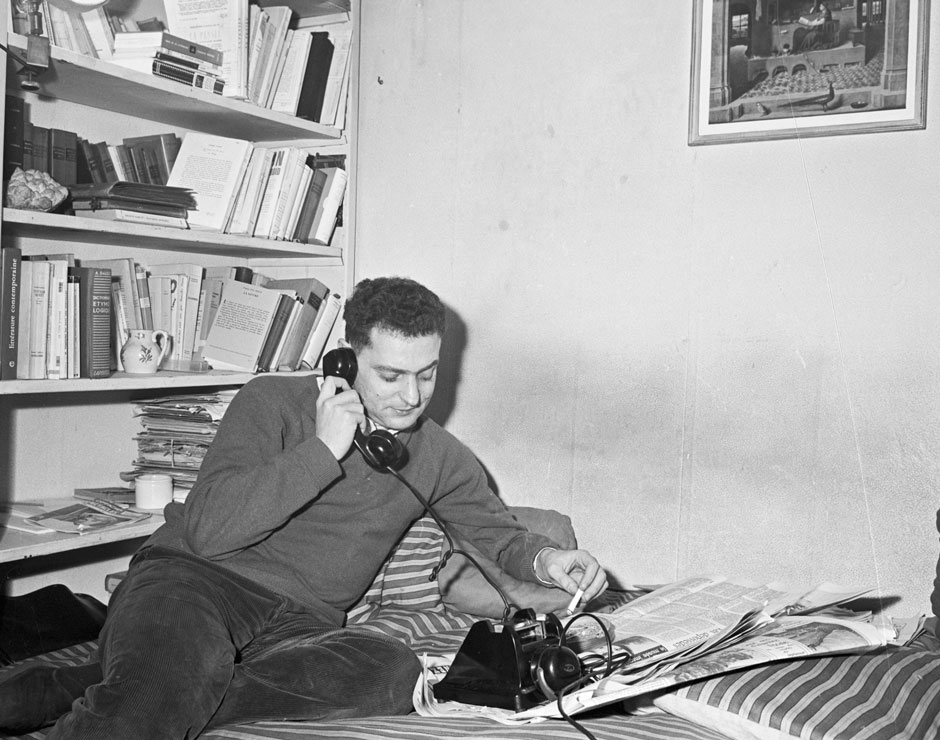

Georges Perec, in bed, near books

Georges Perec, in bed, near books

Georges Perec had a lot to say on this subject in his essay “Brief Notes on the Art and Manner of Arranging One’s Books,” first published in L’Humidité in 1978. An illuminating excerpt:

Ways of arranging books

– alphabetically

– by continent or country

– by color

– by date of acquisition

– by date of publication

– by format

– by genre

– by major periods of literary history

– by language

– by priority for future reading

– by binding

– by series

None of these classifications is satisfactory by itself. In practice, every library is ordered starting from a combination of these modes of classification, whose relative weighting, resistance to change, obsolescence, and persistence give every library a unique personality.

We should first of all distinguish stable classifications from provisional ones. Stable classifications are those which, in principle, you continue to respect; provisional classifications are those supposed to last only a few days, the time it takes for a book to discover, or rediscover, its definitive place. This may be a book recently acquired and not yet read, or else a book recently read that you do not quite know where to place and which you have promised yourself you will put away on the occasion of a forthcoming “great arranging,” or else a book whose reading has been interrupted and that you do not want to classify before taking it up again and finishing it, or else a book you have used constantly over a given period, or else a book you have taken down to look up a piece of information or a reference and which you have not yet put back in its place, or else a book that you cannot put back in its rightful place because it does not belong to you and you have promised several times to give it back, etc.

In my own case, nearly three-quarters of my books have never really been classified. Those that are not arranged in a definitively provisional way are arranged in a provisionally definitive way, as at the OuLiPo. Meanwhile, I move them from one room to another, one shelf to another, one pile to another, and may spend three hours looking for a book without finding it but sometimes having the satisfaction of coming upon six or seven others which serve my purpose just as well.

Samuel Pepys’s library

Samuel Pepys’s library

Samuel Pepys was famously meticulous about his personal library. He limited his collection to 3,000 volumes exactly, and numbered them in order of their size, 1 being the smallest, and 3,000 the largest. According to Henry Petroski’s The Book on the Bookshelf, as a space-saving technique Pepys “arranged his books in double rows, with a slightly raised narrower shelf holding taller books above and behind a line of smaller ones on the main shelf. Such raised shelves also equalize the gap between book tops and the shelf above. ” Pepys was so invested in his system that he was willing to go the extra mile to keep everything perfectly organized. “Where an otherwise matched set of books contained volumes of different sizes,” Petroski explains, “perhaps because they were printed at different times in various formats, Pepys had blocks of wood carved and decorated to match the shorter volumes and lift them up so that they matched in height their mates.” That’s commitment.

Allegra Goodman

Allegra Goodman

Allegra Goodman also goes the double-shelf route. “I organize my books chronologically within subject,” she told the Times, “so, for example, I have all my philosophy together starting with the Pre-Socratics, and I have my literature all together starting with Old English poetry and mystery plays. That’s the plan, anyway. In practice, my books are stacked everywhere, and double shelved. I am that reader who will buy another copy of something I own but cannot find. When my last child leaves for college, I’ll straighten out my books. Maybe.”

Karen Joy Fowler

Karen Joy Fowler

Karen Joy Fowler also has a private system that no one else could ever recreate. In a Locus roundtable, she explained that she has “books all over the house and many are in some kind of order and many are not. When they are in order, it is a private order that makes sense only to me and the organizing principle is social. Richard Butner and Christopher Rowe are close friends so they are next to each other and Christopher is married to Gwenda Bond, so she is next to him. John Kessel is on Richard Butner’s other side and then Jim Kelly. And so on. I taught in Cleveland many summers in a row so all the Cleveland authors are together along with everyone I met at that particular workshop, like Maureen McHugh and Christopher Barzak and Geoff Landis. Only Ursula LeGuin has so many books that she takes up an entire shelf though Stan Robinson is getting close. . . I do have books whose writers I don’t personally know, [however]. Writers I don’t know are sometimes grouped by subject matter, sometimes by my enthusiasm level and sometimes simply by how recent a purchase it is. Or not grouped at all. Setting up the system is one thing. Keeping it up is an endless task where whole bookshelves have to be shifted to fit in some new fat book where it belongs. So lots of time I don’t bother. But I am actually pretty good at turning up the book I want when I want it.”

Brian Evenson

Brian Evenson

Brian Evenson, in that same roundtable, revealed himself to be even more all over the place:

I do try to keep my books organized, but feel like over time I have competing systems that start to cancel one another out. I used to keep all the fiction I had read up at my school office in alphabetical order, but then I ran out of space and started putting it in with unread fiction at home, when I could figure out a way to shoehorn it in. To make that work, I ended up taking the genre fiction out and having a read SF/Fantasy section and a read Mystery section. But then that made me feel that I should separate those out from my unread books as well. I apparently did that in crazy ways, so that, for instance, I seem to have some of Jeff Ford’s books in my SF section and some in the fiction section, and some of those now are read and some unread. I also have sections that are press specific: a Library of America section, a Green Integer Press section, a Melville House section, a Centipede Press section, etc. Then add to that various shelfs and piles of books bought since that I don’t have a place to quite put, and that periodically I try to sort out. And that’s not even the confusing part: at least with fiction it’s still more or less alphabetized and I know that it’s probably in one of three places and if it’s not then I’m almost positive it’s in one of a half dozen more, and if its not there then I’m pretty sure it’s probably in one of the few dozen boxes of read fiction that may or may not be accurately labeled. Usually I don’t need the book bad enough to go after it if I get to that last step . . . But if I do, it’ll be there.

But believe it or not my non-fiction, fiction anthologies,and miscellaneous books are much more chaotically organized, by logics and systems that were long ago forgotten and since overlaid by other equally arbitrary systems. If I’m very lucky, I’ll go right to a book almost by instinct, or I’ll come across an interesting book by happy accident while looking for another. If I’m not, it can take almost forever to find it. I taught this semester a 19th century detective fiction class and was looking for Detection by Gaslight, a book I’d bought back in 1997 when it first came out. I remembered buying it, remembered what it looked like, even was pretty sure where I’d put it, but I ended up looking for it actively and passively for days in August before finally giving up and buying a new copy. I ended up finding just a few days ago, while looking for Delany’s Jewel-Hinged Jaw–which I still haven’t found. . .

Fran Lebowitz at the Strand. Photo: Jason Frank Rothenberg

Fran Lebowitz at the Strand. Photo: Jason Frank Rothenberg

“My books are organized first by category,” Fran Lebowitz told The New York Times. “Fiction, letters, essays. Those kinds of categories. And then there are many subdivisions. Then within categories, they’re alphabetized. I always have arguments with the guy who helps me organize my books, because I have a biography section. He says: “You can’t have a biography section. You have to have them arranged by writer. For instance, Henry James’s fiction, then the letters, the biographies, etc.” And I say: “I know. That’s the right way to do it. But that would take up too much space.” All the apartments I buy or rent are for my books, not for myself. I don’t need the space. I’m 5-foot-4. I have a whole bookcase that this guy calls “your crazy books.” The crazy book category. Those books are not alphabetized.

She also, she explained has a large reference library, with encyclopedias and lots of dictionaries (fiction goes in the living room, reference books go in the writing room). “Nobody uses these books anymore, but I do. When the second edition of the O.E.D. came out, there was nothing I wanted more. It was like $10,000. I had a friend who owned a bookstore, and I begged her to let me buy it at cost, and she did. It was still several thousand dollars, but I’m delighted to own it, even though I think it’s now free on the internet.”

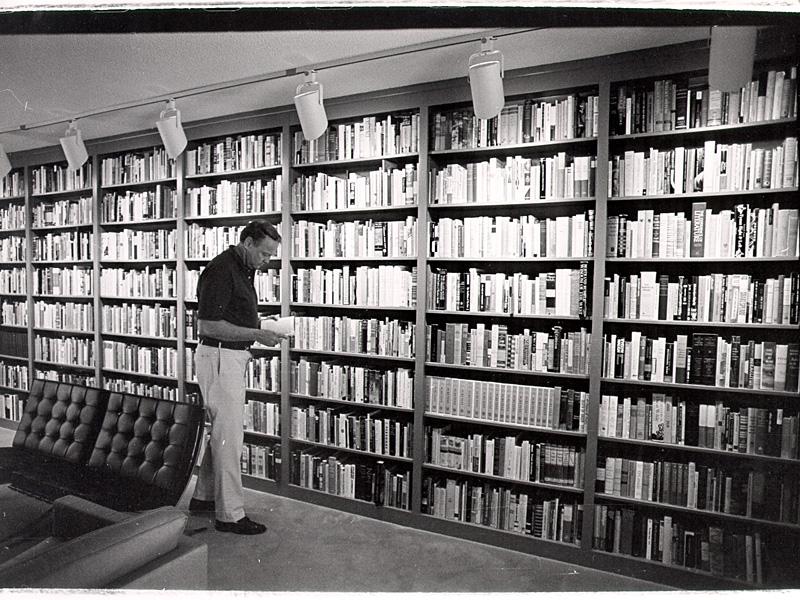

James Dickey in his library. Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

James Dickey in his library. Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

James Dickey kept track of his 20,000-volume library through “strict alphabetizing.” In 1976, he told The New York Times: “I don’t go by country or subject—I’m author‐oriented. . . Too many subjects overlap‐Robert Ardrey can be zoology or metaphysics or political science. All I need is ‘Ardrey’: everything he wrote I put under his name.”

Erica Jong. Photo: Krista Schlueter

Erica Jong. Photo: Krista Schlueter

In 1976, Erica Jong was househunting, and her book collection was scattered. “I think lot of writers arc driven to buy house in the country to have a place for their books,” she told The New York Times. But before her books were scattered to the winds, her system “began by author, by subject and by period, and went on to “cataloging by whim.” She told the Times that she stuck “all the books that reminded me of each other on one shelf, everything from novels by Colette and Jean Rhys to books by Germaine Greer and Shulamith Firestone end pretty soon it grew into a whole care of books by and about women and the women’s movement.”

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.