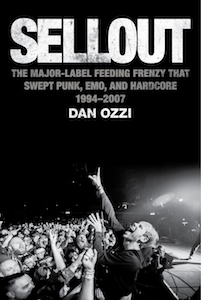

How 11 Punk Bands Took a Leap of Faith, Sold Out, and Shaped Music History

Dan Ozzi on the Impact of Nirvana's Nevermind and the Major-Label Feeding Frenzy that Followed

They arrived with their business cards and with their checkbooks. They descended on dingy rock clubs and dimly lit bars. They talked a smooth game and their shirts were tucked into their jeans. They were major-label A&R scouts and, by 1993, they were everywhere.

The punk scene had names for these sorts of people. They were the corporate villains mocked in song lyrics and torn apart in fanzines. They were called vampires and leeches, and their sole mission was to suck the life out of independent bands and leave them dry. They were the enemy. And now here they were in the flesh, on the lookout for fresh meat.

This wasn’t the first time that the majors had tried to sink their teeth into the genre. A&R reps had first come sniffing around punk rock during its birth in the mid-70s, making unlikely stars of rock ’n’ roll’s antiheroes. Warner nabbed the Ramones, Virgin picked up the Sex Pistols, and CBS had the Clash. Punk infiltrated the system and planted its flag in pop culture. As it grew more popular, its countercultural ethos became part of the mainstream. But the moment was fleeting. After the punk explosion died out toward the end of the decade, due to dwindling cultural cachet and the deaths of some of its figureheads, major labels largely left the underground alone. Once there was no more money to be wrung out of punk, they turned their focus to emerging genres like new wave, R&B, and glam metal.

Throughout the 80s, few bands from the punk, hardcore, and alternative rock realms were even blips on the radars of major-label A&R reps, and with good reason. Much of the music lacked commercial appeal, often deliberately so. Of the handful of bands that were palatable enough to get called up to the majors—Hüsker Dü, the Replacements, Sonic Youth—none of them exactly proved themselves to be winning financial investments. Most were viewed internally at labels as prestige signings—a way for a company to buy themselves some cred and win the respect of critics.

And so, mainstream music and underground rock existed independently of each other for more than a decade without much overlap. On one end was the lucrative establishment, which helped artists dominate Billboard charts, MTV, and national press, and on the other, an autonomous network of small clubs, indie labels, promoters, and distributors struggling to get by. Aside from the anomalies of R.E.M. and U2, who successfully transitioned from college radio to Top 40 stations, there was little crossover between factions. The lines were drawn in crisp black and white.

Then a band from Aberdeen, Washington, came along and wrote an album that flipped the world upside down.

*

No one saw Nirvana coming. When Geffen/DGC Records took a chance on the band’s sophomore album, Nevermind, in September 1991, expectations were modest, with only 46,000 copies shipping to stores in the United States. But thanks to the trio’s small but rabid cult following on the indie rock circuit, the album quickly caught on with young listeners. Aided by minimal marketing, it debuted on the Billboard 200 chart at number 144 and climbed steadily over that month—to 109, then 65, then 35. Once MTV started airing their video for “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” its momentum couldn’t be contained. After just eight weeks, Nevermind had gone platinum.

Following a decade of bombastic, sex-crazed hair metal bands and shiny, mass-market pop acts, the raw and unpretentious Nirvana was the perfect candidate to usher in the fresh look, sound, and attitude of the 1990s. With his dirty Converse sneakers, the band’s greasy frontman, Kurt Cobain, kicked the door open on a new era of rock that prided itself on authenticity and anti-commercialism. As a nation of despondent Gen Xers latched on to Nevermind, Nirvana’s major-label debut organically took on a life of its own. When asked by the New York Times how DGC had created a phenomenon that was soon to unseat King of Pop Michael Jackson at the top of the Billboard charts, label president Eddie Rosenblatt shrugged. “We didn’t do anything,” he admitted. “It was just one of those get-out-of-the-way-and-duck records.”

Nevermind’s meteoric rise put the last nail in the coffin of the 1980s and torched any lingering hair metal popularity. Leather pants and teased hair gave way to ripped jeans and flannel shirts. “Cum On Feel the Noize” was out; “Come as You Are” was in. Radio stations, MTV, and record labels had a newfound interest in guitar bands that were grittier and edgier. Tastemakers ravenously combed local scenes for the next Nirvana, the next Kurt Cobain, the next Seattle. Ten years of DIY culture and its entire movement had finally hit a tipping point and fundamentally changed the world. “Grunge” was now the hot new industry term, and everything in its orbit was in demand. Suddenly, the underground was financially viable, and the lines that had been black and white turned gray. Or, more accurately, green, as money started flowing into the underground from the corporations trying to buy it all up.

What followed in the wake of Nevermind has been described as a major-label feeding frenzy, an A&R gold rush, and an indie rock signing blitz. A&R reps raced one another to mine previously untapped scenes where rock music was thriving, in hopes of discovering the next breakout stars. After they’d fully pillaged Nirvana’s stomping grounds in Seattle, they searched elsewhere—DC, San Diego, Chapel Hill—and eventually landed in San Francisco. That’s where this book begins—with a catchy punk trio from the East Bay called Green Day, who inked a deal with Reprise Records in the summer of ’93 for the release of their third album, Dookie.

*

After Green Day left the indie world for the mainstream, a flood of other punk bands were given the chance to follow. A&Rs tried winning them over with fancy dinners and hefty bar tabs charged to the company card. Blue hair and piercings could be spotted in meeting rooms at label offices in New York and Los Angeles. The support system these bands were being offered was enticing—proper studio accommodations, budgets to make music videos, and placement in malls and chain stores like Sam Goody and Tower Records. For bands that considered themselves lucky to earn enough gas money to drive their Econoline vans to the next town each night, these luxuries were often well beyond the ceiling of their modest imaginations.

But with this opportunity came a catch. The insular underground communities that had incubated these musicians were not about to let their scene be ransacked again without a fight. After a decade of carving out their own space, punks grew protective of the DIY network they’d built. As they fought to secure their independence, fists were raised and spikes were drawn. Punk imposed an unofficial set of rules on itself and was unkind to those who broke them. A line was drawn in the sand: any band signing with the Big Six—Sony Music, EMI, MCA/Universal, BMG, PolyGram, and Warner Music Group—was doing business with the devil. They risked being banished, ostracized, or forever branded as sellouts.

What followed in the wake of Nevermind has been described as a major-label feeding frenzy, an A&R gold rush, and an indie rock signing blitz.

For more than a decade, punk’s second brush with mainstream interest bitterly divided the scene. The most ardent defenders of the underground grew militant toward those bold enough to break out of the communities that had birthed them. To toe the line, longtime fans found themselves turning their backs on bands to which they’d once been so devoted. Some “sellouts” got off light, with backlash that amounted to disgruntled columns in fanzines or snarky comments on the internet. For others, it meant being barred from their favorite clubs and being threatened with physical violence.

The notion of selling out didn’t originate in the 90s, of course, nor was it relegated to punk rock or even music, for that matter. For as long as people have been offered the chance to profit in exchange for compromising their ideals and morals, cynics have been there to call them out for it. But the loaded term gained traction during this period as major labels began waving dollar signs in the faces of young musicians. Whether a band had gone major or stayed true to their indie roots became a defining characteristic in how they were perceived by their peers.

This book captures the stories of 11 bands at the pivotal moment in each of their careers when they signed with a major label—how they arrived there, why they decided to go for it, and what it did to their career. Each chapter chronicles one band’s history around the release of their major-label debut album, a crucial and often tumultuous period that could make or break them. A few of these bands saw their gamble pay off and were rewarded with Grammy statues and platinum records. But for every success story, there were dozens of bands that collapsed under the pressure, leaving members beating the shit out of each other on the side of the highway. This is not an attempt to pick winners and losers, though. Too often, when art is viewed through the lens of capitalism, it is reduced to a gamble that either pays off or doesn’t. Quite the contrary. Some bands released their best and most fully realized work through major labels, even if it didn’t immediately translate into sales.

In no way is this book a comprehensive history of every punk band that made the jump. Plenty of bands with interesting major-label experiences had to be omitted. Sadly, Cave In didn’t make the cut, despite a winding career during which they transformed from a gnarling hardcore band to a polished rock group making an over-blown studio album for RCA Records. Anti-Flag is another interesting case, in which a mohawked political punk band with songs like “Kill the Rich” triggered a major-label bidding war after landing on the radar of Svengali producer Rick Rubin. Hell, Chumbawamba was a group of anarcho-punks who signed to EMI and wrote an accidental pub hit with their sing-along track “Tubthumping.” Once they were in the spotlight, they used their platform to espouse feminism, animal rights, and class warfare in interviews. Singer Alice Nutter advised people to steal their albums from chain stores and once sparked outrage when she told Melody Maker, “Nothing can change the fact that we like it when cops get killed.” That’s a story worthy of its own book.

The 11 bands documented here were chosen because they were integral in shaping the trends that propelled the post-Nirvana alternative music boom forward. Each of them helped drive commercial interest into new territories, and thanks to their efforts, the genre had room to adapt and broaden its scope, far surpassing the limits it had reached in the 70s. Punk mutated and took on new forms as the sonics and geography of it shifted, from the Bay Area pop-punk sound to the hardcore screams emanating from the basements of New Brunswick, New Jersey, to a new wave of emo that existed not so much in any regional location as on the internet.

Punk’s great sellout divide fostered one of the most heated and antagonistic eras of rock history. This is a book that explores the gray areas found where finance and artistry clash, and where opportunity and integrity collide. It’s a story in which a few distorted power chords turned into a multi-million-dollar cultural phenomenon. And it all started as the sun was setting over San Francisco one evening and three punk kids turned up at the office of their independent record label, ready to take a leap of faith.

__________________________________

Excerpted from SELLOUT by Dan Ozzi. Copyright © 2021 by Daniel Ozzi. Reprinted by permission of Mariner Books, a division of HarperCollins Publishers LLC.

Dan Ozzi

Dan Ozzi is a New York-raised, Los Angeles-based writer. Along with Against Me!'s Laura Jane Grace, he co-authored 2016's TRANNY, which was listed in Billboard's "100 Greatest Music Books of All Time." He has contributed to The Guardian, SPIN, Billboard, The Fader, and others.