All evening, Stewart has behaved properly. Of this he is certain. Now it is late though, and night coaxes him into its arms. They are in his father’s car, his mother in the front seat, he in the back, driving to his father’s house in the country, where they will stay until morning.

Soon it will be Christmas, and this is a special occasion. His father invited them to a ballet, a performance with soldiers and swords and sugar plum fairies in flowing white gowns. “Promise me you do your best to be good,” his mother instructed today, as they were getting ready to drive to his father’s house from their apartment in Denver. His father lives at the edge of a forest with towering trees. “If he gives us the check, I buy you the coloring pens you want from the store.” Heike had explained her plan to Stewart painstakingly, going over every detail. She needs his father to give them two thousand dollars so they can buy a new car and drive to California together. Otto, her bug, is too old to travel this great a distance.

The moon is full, the freeway empty and open. Looking out the window, Stewart conjures images of wild animals—a lion roaring into his face, a puma, black and sleek, chasing him in the night— but the car is warm, and his eyelids are heavy. Each time he drifts off, he catches himself. He knows his father doesn’t want to have to carry him into the house.

The fields, covered in snow, glow under the sky. This is the time, Stewart knows, when fairies emerge from the woods and dance like confetti, when mice form their armies.

“I love The Nutcracker so much,” his mother says. “They play it so beautiful.” Stewart rests his cheek on the window’s cold glass, feels the moon’s palm on his skin.

“Beautifully,” says his father, his voice like a blade. “Beautifully,” she repeats. Stewart says the word too, silently. Sometimes, when he and his mother are driving at night, Stewart will point out things he sees in the distance. A caravan of elephants. A haunted castle. A giant octopus moving toward a river. Usually she’ll play along, pretending to see the things he describes. Now, though, there is nothing outside. He does his best to keep watch, to find shapes in the fields—once or twice he spots a wolf or a fox or maybe a tiger crouching in the snow, then dashing for cover—but it becomes harder and harder to keep his eyes open.

“Stewart,” his father says. “Wake up now, kiddo. Don’t make me say it again.”

His mother is sitting at the kitchen table, practicing the corrections his father wrote in pen on a sheet of lined paper.

The dog’s fur is brown. (Never “The fur of my dog . . .”) There are three of us. (Never “We were three”)

We were on the scooter, but then we got in the van. (In vs. On)

If I have enough butter, I will make a pound cake. (Not “would have”)

I bought a new dress. How does it look? (Never “look like”) I feel happy today. (Never reflexive!)

She holds the paper in one hand and balances Stewart on her lap with the other. He watches her mouth as it moves, her cheeks and her chin, and he’s reaching out to touch one of the curlers in her hair when a rat bursts through the window above the sink, its claws shattering the glass like a dragon enraged. The rat is large as a bear, yet what Stewart hears is not the sound of glass breaking, but something grating: the sound of wheels on gravel. Even before he opens his eyes, he knows they are close. He wills himself awake, sits up straight and tall.

The rat’s bulging eyes, its pointed whiskers and teeth, the sharp claws, still inhabit his mind as he sees, through the window, the outline of soaring pine trees, so close he is certain their snow covered branches will graze the car’s body.

“There is nothing to be afraid of,” his mother once told him. “The forest is full of magic and wonder. When I was a girl, Omi and I hiked for hours in the woods, collecting blueberries and strawberries and then, at the end of the summer, raspberries so ripe they turned to juice in your fingers. When we returned home, Omi put the fruit in a pot on the stove and boiled the berries with sugar until our tiny hut smelled like it was made from warm syrup.”

Night air fills his lungs, like menthol or flames, and he waits next to his mother while his father opens the door. The house is a fortress of wooden beams and concrete, surrounded by bushes and shrubs covered in snow. Once they’re inside, Stewart’s mother folds his clothes, helps him put on the pajamas she brought over in her grocery store bag. His bed is a mattress laid out under a huge printing press, made—his father told him—in England during the reign of a king who beheaded nine men, including his own uncle and brother.

“Did he do his reading today?” his father asks.

His mother hesitates. “Today? Not today, but every other day we have been reading.”

“Well, it has to be every day.” His father stands like a warrior in his undershirt and white briefs.

Stewart knows what his mother is thinking. First thing in the morning I must read with my son. There will always be groceries to buy and pants to wash out. Already his walkjanker is get ting too small. I should have bought him something warmer in wool.

“Stewart,” his father says, “come here.” He strides to the book shelf and picks out Grimm’s Fairy Tales. “Why don’t we read one of these stories.”

“But, Raymond, look what time it is. The boy should be already in bed.”

“He’s fine, Heike. Aren’t you, kiddo? Come over here, son.”

Stewart walks toward his father, whose undershirt is tight across the muscles of his chest. They sit on the couch, and his father asks which story he wants to read. Stewart studies the table of contents; the words seem to dance on the page.

“How about Hansel and Gretel?” his father asks. His mother has told him the story many times, each version slightly different from the previous.

His father finds the page and puts the book on Stewart’s lap. Stewart’s hands are already sweating. “Once upon a time,” he begins, “there was a poor woodcutter who lived on the edge of a big forest”—he sounds each word out slowly, even the words he has seen before—“with his wife, who was not . . .” He pauses, looking at the word.

“You know this,” says his father. “Es-pe-k-a-ly,” Stewart tries.

“Especially,” his mother says. She is standing a few feet away, gripping her nightgown.

“Don’t help him, Heike.”

The next word is just as hard. Stewart isn’t sure how to say it. He mouths the letters to himself, but everything jumbles. He knows what goes on in the story. It’s about a mother and father who are poor and can’t feed their children.

“Stewart, you’ve got to pay attention. This is only the first sentence.”

“B-eee-out-i-ful,” he says, sounding out the word almost inaudibly as the letters begin to float into the air.

“I can’t hear you,” his father says.

Stewart tries again, using all of his strength. He struggles to hold the pages in place, wills each letter still.

“B-EEE-OWT-I-FUL is not a word, Stewart. Do you know what B-EEE-OWT-I-FUL means?”

His body is hot, as if someone had turned on a furnace. His father’s arm weighs down across his shoulders and neck.

“Raymond,” his mother says. “Please. This is too much.” Stew art knows his mother wants to say more. If she had gotten the money this afternoon, she could take Stewart and leave. Why did I not ask for the check when my lipstick was nice and my hair had not flown away? Today was so windy. It made me a mess.

“Quiet, Heike.”

Stewart’s throat contracts. If he lets even the smallest bit of air into his mouth, he knows he will cry. He strains to keep his eyelids wide, like a surfacing fish.

“Come on, Stewart. Start the sentence from the beginning, and think about what word makes sense in context.”

Stewart reads the words to his father, one by one, making sure no letter moves. When he gets to especially, he freezes. He knows his mother just told him the answer. He makes the e sound and the sp sound. Then it happens again—the tail of the y curls up from the paper, reaching out toward him, like the tail of a lizard or an iguana or a black dragon. It lassoes his neck, tugging the l and the a and the i, pulling free from the page. He watches the letters peel up—the word, then the sentence itself, like a streaming ribbon, slippery as a minnow.

“Stewart! Don’t fart around. You just said it.”

Something breaks in his throat. His breaths come short and fast, like choking or the collapsing of lungs.

“Okay. That’s it! Go outside until you calm down.” “Outside?” says his mother. “He can’t go outside. It’s the middle of the night!”

He’s afraid his father might hit her. When his father starts yelling, his stubbled face often turns lava red.

“Outside, Stewart.”

He feels the sounds coming out of his father’s mouth. He gets up from the couch, his pajamas wet on his skin. His mother looks around for her shoes. He walks toward the front door, and she hurries over to him. She puts his arms into the sleeves of his jacket, then helps him open the door. She steps outside with him, but his father says, “No, Heike—you stay here.” She pauses, looking at the man, then back at her son.

“You be okay,” she says. “Nothing will happen. Think of what Mommy has said.”

The air envelops him like a sea made of ice. His eyes adjust to the night. Above him, the sky glows with stars and the luminous moon: large and white and perfectly round.

Once there was a boy who was lost in the woods, and he walked and walked in the night. The villagers all thought he would not find his way home, and they took lanterns and went out into the forest to look for his footprints. Hour after hour, they searched for their Bübchen. The later it got, the brighter became the stars and the moon. They cast light so the boy could see in the night, and they kept him company out in the snow. The boy did not grow afraid—he sang songs to himself, and, as he sang, the animals came out of the forest. The owls and squirrels and deer brought him baskets of food. Do not be afraid, the moon said to the boy. I am here to protect you.

Stewart watches the moon. His mother is right. If you look closely enough, you can see a man’s face. It smiles at him. He sees the stars stretching out toward him, reaching down through the trees. Inside the house he hears his mother crying. “Why are you like this to us? I made myself beautiful. Is this not the outfit you thought I should wear?”

He listens for his father’s response but hears nothing at all. A few months ago, Stewart was visiting his father for the week end, and they went to see Mary Poppins. His father bought him licorice and soda and told him they could sit in any seat Stewart chose. “I bet your mother doesn’t buy you licorice when you go out,” his father said. Later, as they were driving home, he asked Stewart a question: “Your mother still taking baths together with you? Tell me the truth.”

Stewart didn’t respond. His eyes were closed, and he was starting to dream. “I’m waiting, Stewart. Don’t be like your mother now.”

He wasn’t sure what to say; he was thinking about the bubbles that piled up on top of the water. He liked it when his mother put a beard on his cheeks or a cap on top of his head. He was thinking about the way she poured the green gel into the water as it filled up the tub.

“It’s okay, son. I know this hasn’t been easy on you.”

He wonders whether his father is standing on the other side of the door now, waiting. Perhaps he has gone into the bathroom to pick at his teeth. Maybe he will change his mind and make his mother stand outside too. If they both have to sleep in the woods, they can build a house made of snow, like the Eskimos do in the North. They can use branches from pine trees to keep themselves warm.

In the distance, the ground spreads out like a carpet of silver. The moon begins to approach, step by step. “Come closer,” it beckons. “It’s okay.”

Stewart sees the branches in the woods sway back and forth. He wonders whether the trees move in the wind because they are trying to stand close together, for warmth, or whether they are trying to dance. Each tree in a past life was a famous ballerina who was graceful and nimble and beautiful.

Stewart is at the far end of the gravel driveway when he hears his father call his name. He stops, the voice distant and small. “Stewart?” his father repeats. “You still out here, kiddo?”

He turns and sees the man, in socks, in the doorway, a half figure looking into the darkness. “You better come back inside. It’s getting late. I made up your bed.”

“We’re waiting for you,” the moon says to him. “The dancers are ready to start.” Up ahead, he sees two reindeer come out from the bushes, and several squirrels; they are carrying something for him, a basket of Zwetschgenkuchen and Pfeffernüsse and perhaps something else. He walks quickly, snow thick underfoot, his father’s words lost in the night.

__________________________________

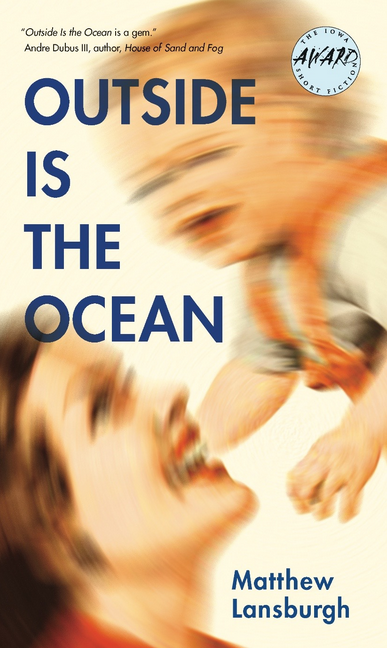

From Outside Is the Ocean. Used with permission of University of Iowa Press. Copyright © 2017 by Matthew Lansburgh.