House Cats and Wild Cats Aren’t Actually That Different

John Gray on the Complex Relationship Between Humans and Felines

At no point were cats domesticated by humans. One particular type of cat—Felis silvestris, a sturdy little tabby—has spread world-wide by learning to live with humans. House cats today are offshoots of a particular branch of this species, Felis silvestris lybica, which began to cohabit with humans some 12,000 years ago in parts of the Near East that now form part of Turkey, Iraq and Israel. By invading villages in these areas, these cats were able to turn the human move to a more sedentary life to their advantage. Preying on rodents and other animals attracted by stored seeds and grains and snatching waste meat left behind after slaughtered animals had been eaten, they turned human settlements into reliable food sources.

Recent evidence points to a similar process taking place independently in China around five millennia ago, when a central Asian variety of Felis silvestris pursued a similar strategy. Having entered into close proximity with humans, it was not long before cats were accepted as being useful to them. Employing cats for pest control on farms and sailing vessels became common. Whether as rat-catchers, stowaways or accidental travellers, cats spread on ships to parts of the world where they had not lived before. In many countries today, they outnumber dogs and any other animal species as cohabitants of human households.

Cats initiated this process of domestication, and on their own terms. Unlike other species that foraged in early human settlements, they have continued to live in close quarters with humans ever since without their wild nature changing greatly. The genome of house cats differs in only a small number of ways from that of its wild kin. Their legs are somewhat shorter and their coats more variously colored. Even so, as Abigail Tucker has noted, “Cats have changed so little physically during their time among people that even today experts often can’t tell house tabbies from wild cats. This greatly complicates the study of cat domestication. It’s all but impossible to pinpoint the cats’ transition into human life by examining ancient fossils, which hardly change even into modernity.”

Unless they are kept indoors, the behavior of house cats is not much different from that of wild cats. Though the cat may regard more than one house as home, the house is the base where it feeds, sleeps and gives birth. There are clear territorial boundaries, larger for male cats than for females, which will be defended against other cats when necessary. The brains of house cats have diminished in size compared with their wild counterparts, but that does not make house cats less intelligent or adaptable. Since it is the part of the brain that includes the fight-or-flight response that has shrunk, house cats have become able to tolerate situations that would be stressful in the wild, such as encountering humans and unrelated cats.

One reason cats were accepted by humans was their usefulness in reducing rodent populations. Cats eat rodents, and thousands of years ago were already eating mice that had eaten grain from human food stores. Yet in many environments cats and rodents are not natural enemies, and when they interact they often share a common resource such as household garbage. Cats are not very efficient as a means of pest control. House mice may have co-evolved with house cats, and learned to coexist with them. There are photographs of cats and mice together, only inches apart, in which the cats show no interest in the mice at all.

A more fundamental reason why humans accepted cats in their homes is that cats taught humans to love them. This is the true basis of feline domestication. So beguiling are they that cats have often been seen as coming from beyond this world. Humans need something other than the human world, or else they go mad. Animism—the oldest and most universal religion—met this need by recognizing non-human animals as our spiritual equals, even our superiors. Worshipping these other creatures, our ancestors were able to interact with a life beyond their own.

Unlike other species that foraged in early human settlements, cats have continued to live in close quarters with humans.Since their domestication of humans, cats have not needed to rely on hunting for their food. Yet cats remain hunters by nature, and when sustenance is not available from humans they soon return to a hunting life. As Elizabeth Marshall Thomas writes in The Tribe of Tiger: Cats and Their Culture, “The story of cats is a story of meat.” Big or small, cats are hyper-carnivores: in the wild, they only eat meat. That is why big cats are so endangered at the present time.

The rise of human numbers means expanding human settlements and shrinking open spaces. Cats are highly adaptable creatures, thriving in jungles, deserts and mountains as well as the open savannah. In evolutionary terms they have been extremely successful. Yet they are also extremely vulnerable. When their habitats and sources of food cease to be available, they are forced into conflicts with humans they are bound to lose.

Hunting and killing their food is instinctive in cats, and when kittens play it is hunting they are playing at. Cats need meat to live. They can digest vital fatty acids only when these are found in the flesh of other animals. The meat-free life of the moralizing philosopher would be death to cats.

How cats hunt tells us a good deal about them. Apart from lions, which hunt in packs, cats hunt alone, stalking and ambushing their prey, often at night. As ambush predators, cats have evolved for agility, jumping and pouncing in the pursuit of smaller prey. Wolves—the evolutionary ancestors of dogs—hunt for larger prey in groups held together by relationships of dominance and submission. Male and female wolves may mate for life, and both take care of offspring. None of these features of wolf behavior is found in cats. The way cats relate to one another follows from their nature as solitary hunters.

It is not that cats are always alone. How could they be? They come together to mate, they are born in families and where there are reliable food sources they may form colonies. When several cats live in the same space a dominant cat may emerge. Cats may compete ferociously for territory and mates. But there are none of the settled hierarchies that shape interactions among humans and their close evolutionary kin. Unlike chimps and gorillas, cats do not produce alpha specimens or leaders. Where necessary, they will cooperate in order to satisfy their wants, but they do not merge themselves into any social group. There are no feline packs or herds, flocks or congregations.

That cats acknowledge no leaders may be one reason they do not submit to humans. They neither obey nor revere the human beings with which so many of them now cohabit. Even as they rely on us, they remain independent of us. If they show affection for us, it is not just cupboard love. If they do not enjoy our company, they leave. If they stay, it is because they want to be with us. This too is a reason why many of us cherish them.

How cats hunt tells us a good deal about them. Apart from lions, which hunt in packs, cats hunt alone, stalking and ambushing their prey, often at night.Not everyone loves cats. In recent times they have been demonized as “an environmental contaminant . . . like DDT,” which spread diseases such as rabies, parasitic toxoplasmosis and the pathogens responsible for the Black Death. Bird droppings pose a greater risk to human health, but one of the commonest accusations against cats is that they kill so many birds. The case against them is that they disrupt the balance of nature. Yet it is hard to explain hostility to cats in terms of any risks they may pose to the environment.

The danger of disease can be countered by programmes such as trap-neuter-return (TNR), widely implemented in the US, in which cats living outdoors are brought to clinics for vaccination and spaying and then released. The risk to birds can be diminished by bells and similar devices. More to the point, it is strange to single out one branch of a nonhuman species as a destroyer of ecological diversity when the major culprit in this regard is the human animal itself. With their superlative efficiency as hunters, cats may have altered the ecosystem in parts of the world. But it is humans that are driving the planetary mass extinction that is currently underway.

Hostility to cats is not new. In early modern France it inspired a popular cult. Cats had long been linked with the devil and the occult. Religious festivals were often rounded off by burning a cat in a bonfire or throwing one off a roof. Sometimes, in a demonstration of human creativity, cats were hung over a fire and roasted alive. In Paris it was the custom to burn a basket, barrel or sack of live cats hung from a tall mast. Cats were buried alive under the floorboards when houses were built, a practice believed to confer good fortune on those who lived there.

On New Year’s Day 1638, in Ely Cathedral, a cat was roasted alive on a spit in the presence of a large and boisterous crowd. A few years later Parliamentary troops, fighting against Royalist forces in the English Civil War, used hounds to hunt cats up and down Lichfield Cathedral. During popeburning processions in the reign of Charles II, the effigies were stuffed with live cats so that their screams would add dramatic effect. At rural fairs a popular sport was shooting cats suspended in baskets.

In some French cities, cat-chasers put on a livelier show by setting fire to them and pursuing them as they were burning through the streets. In other entertainments, cats would be passed around so that their fur could be torn off. In Germany the howls of cats tortured during similar festivals was called Katzenmusik. Many carnivals concluded with a mock trial in which cats were bludgeoned half to death and then hanged, a spectacle that evoked riotous laughter. Often cats were mutilated or killed as embodiments of forbidden sexual desire. From St Paul onwards, Christians viewed sex as a disruptive and even demonic force. The freedom of cats from human moralities may have become linked in the medieval mind with the rebellion of women and others against religious prohibitions on sex. Against the background of this kind of theism it was almost inevitable that cats should be seen as embodiments of evil. Throughout much of Europe they were identified as agents of witchcraft and tormented and burned along with or instead of witches.

The practice of torturing cats did not end with the witchcraft craze. The 19th-century Italian neurologist Paolo Mantegazza (1831–1910), professor at the Istituto di Studi Superiori in Florence, founder of the Italian Anthropological Society and later a progressive member of the Italian Senate, was an avowed Darwinian who believed humans had evolved into a racial hierarchy with “Aryans” at the top and “Negroids” at the bottom. The distinguished professor devised a machine he jovially entitled “the tormentor.” Cats were “quilted with long thin nails” so that any movement was agony, then flayed, lacerated, twisted and broken until death at last released them. The aim of the exercise was to study the physiology of pain. Like Descartes, who refused to abandon the theistic dogma that animals have no soul, the eminent neurologist believed that the torture of animals was justified by the pursuit of knowledge. Science perfected the cruelties of religion.

That cats acknowledge no leaders may be one reason they do not submit to humans. They neither obey nor revere the human beings with which so many of them now cohabit.At bottom, hatred of cats may be an expression of envy. Many human beings lead lives of muffled misery. Torturing other creatures is a relief, since it inflicts worse suffering on them. Tormenting cats is particularly satisfying, since they are so satisfied in themselves. Cat-hatred is very often the self-hatred of misery-sodden human beings redirected against creatures they know are not unhappy.

Whereas cats live by following their nature, humans live by suppressing theirs. That, paradoxically, is their nature. It is also the perennial charm of barbarism. For many human beings, civilization is a state of confinement. Ruled by fear, sexually starved and filled with rage they dare not express, such people cannot help being maddened by a creature that lives by affirming itself. Tormenting animals diverts them from the dismal squalor in which they creep through their days. The medieval carnivals in which cats were tortured and burned were festivals of the depressed.

Cats are disparaged for their apparent indifference to those that care for them. We give them food and shelter, yet they do not regard us as their owners or their masters, and they give us nothing back except their company. If we treat them with respect, they grow fond of us, but they will not miss us when we are gone. Lacking our support, they soon re-wild. Though they display little concern for the future, they seem set to outlast us. Having spread across the planet on the ships human beings used to expand their reach, cats look like being around long after humans and all their works have vanished without trace.

__________________________________

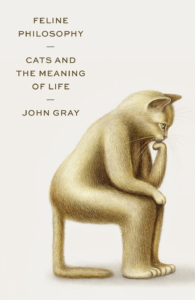

From Feline Philosophy: Cats and the Meaning of Life by John Gray. Used with the permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Copyright © 2020 by John Gray. All rights reserved.