“Horseshit!” Yes, Marlon Brando, Eclectic Bibliophile, Wrote in His Books

Rebecca Rego Barry Digs Through the Actor’s Personal Library as it Heads to Auction

All images credited to Bonhams

In Marlon Brando’s most famous acting roles, he plays the strong, violent type: Stanley Kowalski in the A Streetcar Named Desire; longshoreman Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront; and, of course, gangster Don Corleone in The Godfather. That notoriety sometimes spilled over into accounts of his real life, too—when Truman Capote profiled him in the New Yorker in 1957, he portrayed Brando as a “self-absorbed” and “partly educated” mumbler.

Capote was unfair at best, vicious at worst. Brando had indeed left school without a diploma and suffered a mild form of dyslexia, according to his biographer, William J. Mann, author of The Contender (2019), but he was intent on educating himself. “Fellow actors would come upon him as he lugged home eight, nine, or ten books that he’d picked up at used bookstores,” he said.

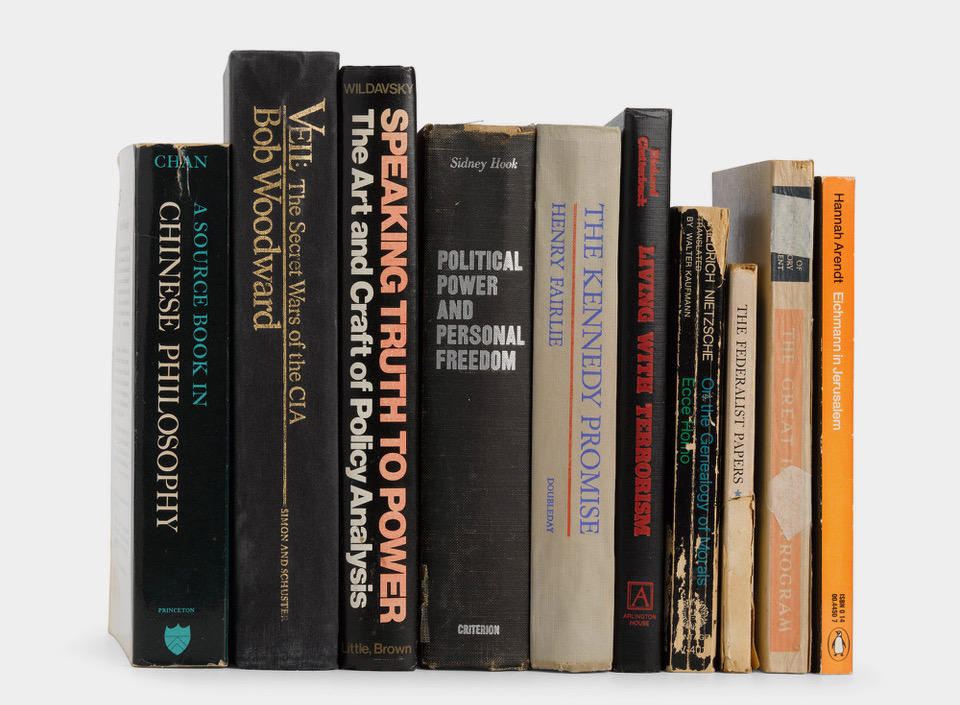

Brando’s personal library of 3,000+ books, headed to auction in Los Angeles on June 8, shows a broad-minded and attentive reader, in subjects spanning art, literature, psychology, politics, and more, with notes (“Horseshit!”) often scribbled in the margins. “I think he always had this sort of reputation for being a kind of thug . . . but you know, that wasn’t him at all,” said Helen Hall, entertainment and music specialist at Bonhams auction house.

Hall is well-acquainted with the actor’s library. When Brando’s estate first went to auction in 2005, it was she who packed up the books from his Mulholland Drive mansion. “The majority of them were all on bookshelves above his bed, a whole wall of bookshelves with his bed in the middle of it,” she explained. Most of the books sold then to one Brando fan, who has now decided to let them go.

Brando had indeed left school without a diploma and suffered a mild form of dyslexia, but he was intent on educating himself.

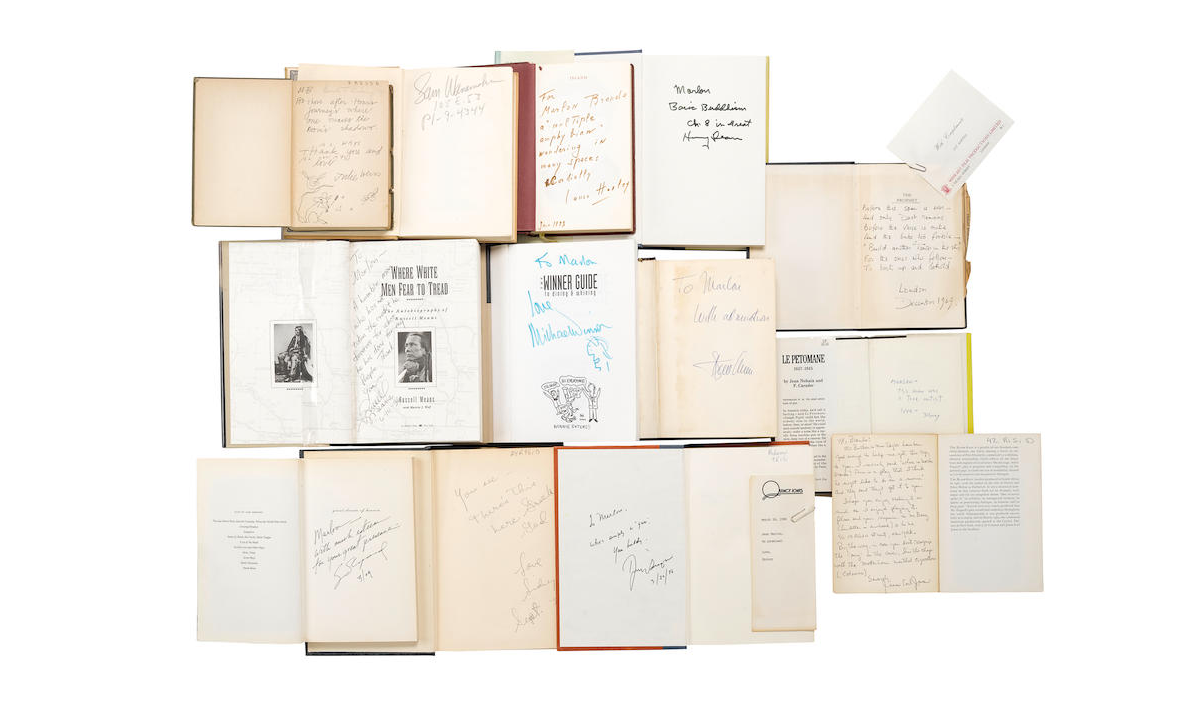

Most of Brando’s books will be offered in themed lots containing dozens or hundreds of books in each. As one would expect, his library boasts a fair amount of books inscribed to him by the author or presented to him by celebrity friends. Among those 315 volumes grouped together for an estimated $15,000-25,000 is a 1968 biography of French mime/flatulist, Le Petomane, inscribed in blue ink to Brando from Johnny Depp: “Marlon = This man was a True artist. Love = Johnny.” The two actors had worked on a few films in the mid-90s and became fast friends.

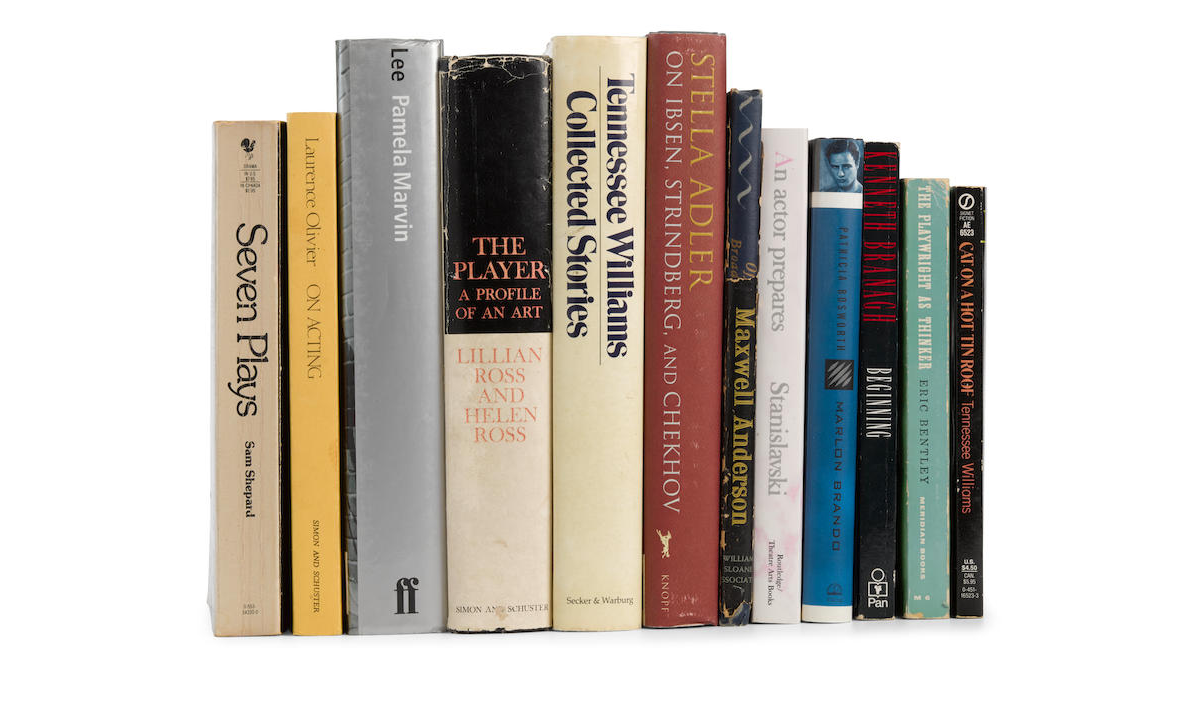

The books that can be linked to the two-time Academy Award winner’s career are likely to conjure the most collector interest. The scripts and movie memorabilia, particularly related to The Godfather and Apocalypse Now will surely fetch the big bucks, but the gathering of 95 books on acting, film, and theater, “some with portions of the text underlined and highlighted or with notes in the margin in Brando’s hand,” might get closer to the man himself. If he bought his copy of Maxwell Anderson’s Off Broadway: Essays about the Theater (1947) when it was first published, he might have been reading it backstage during Streetcar’s Broadway run; he was known to keep a shelf of reading material in his green room. Here too are later editions of books by his teacher and mentor, Stella Adler, and Russian actor/director Konstantin Stanislavski, whose performance techniques Adler introduced to Brando.

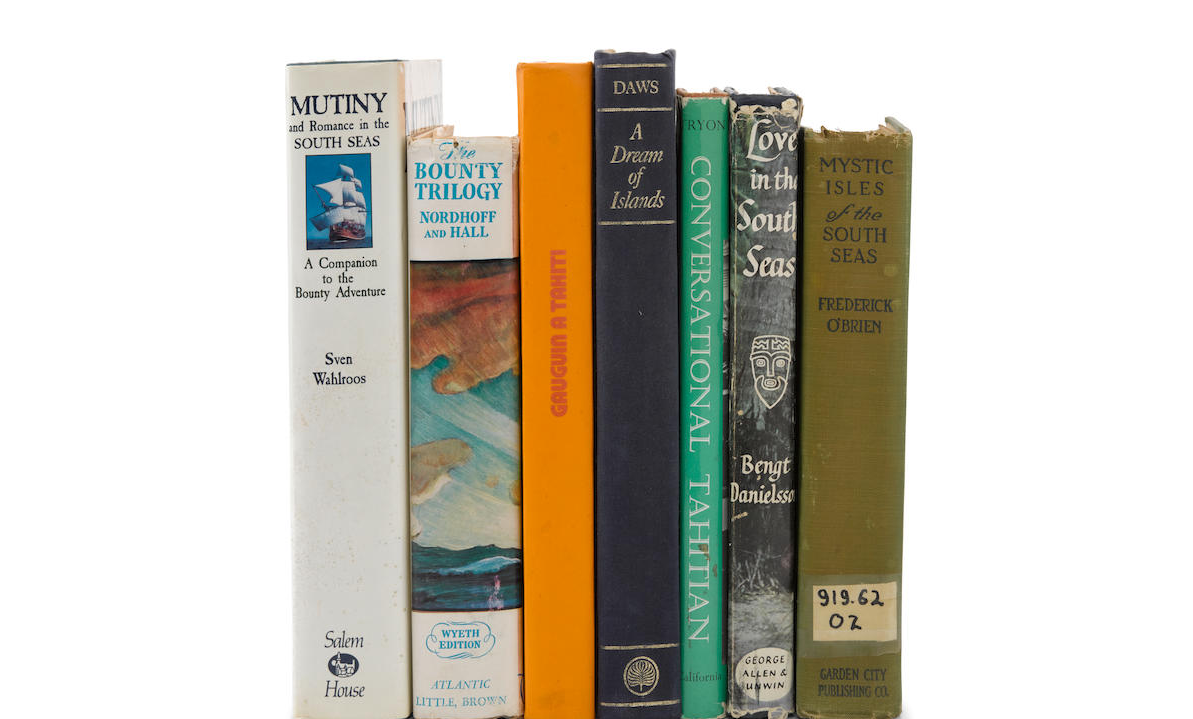

Fifty books about Tahiti sounds like a lot, but, Hall explained, Brando’s interest could be pinned to the 1962 remake, Mutiny on the Bounty, in which he played head mutineer Fletcher Christian. (Fun facts: Brando’s second wife starred in the original 1932 Mutiny film, and his third wife played in the later version.) He was so enamored of French Polynesia, he bought an island, Tetiaroa, today the site of a luxury resort named The Brando that could really impress its guests by spending $1,000-1,500 to buy these books and install them as a resort library, no? Featured in this cluster are books about coral reefs and Gauguin.

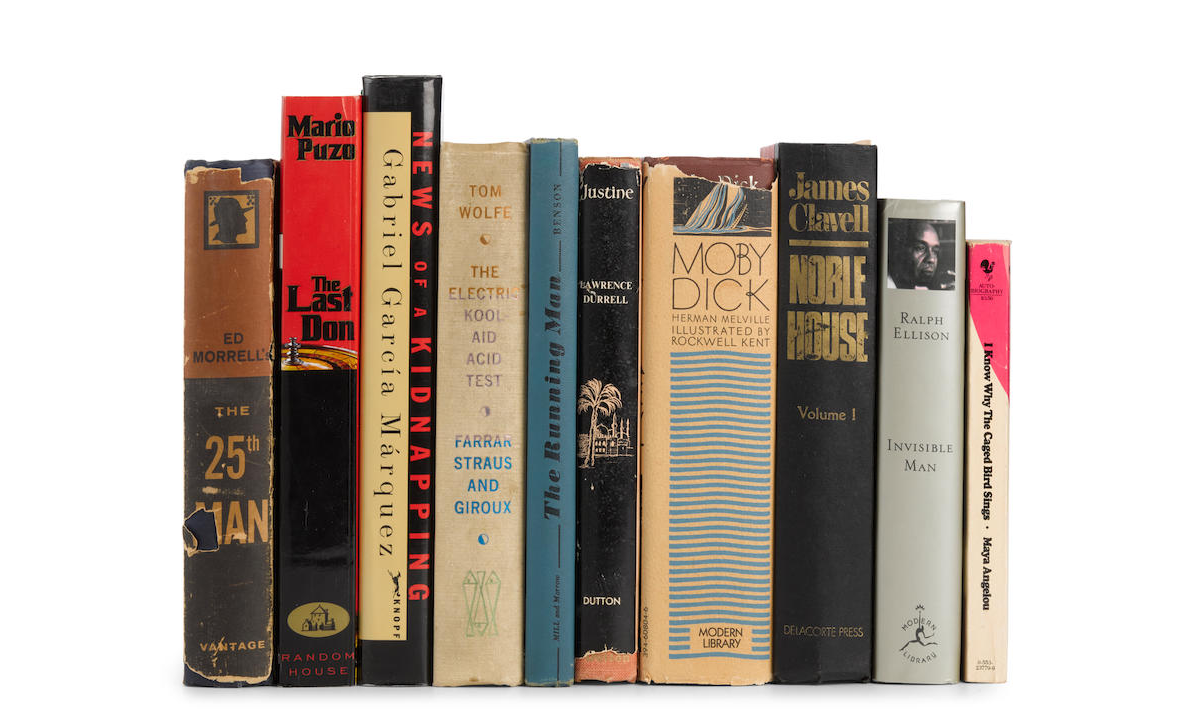

Brando didn’t care much for novels, said Mann, preferring poetry, but still his library wasn’t without highbrow fiction and contemporary literature, again bearing his marginalia. Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Maya Angelou, and Ralph Ellison merited a place alongside about 260 other volumes, though it’s hard not to focus on Mario Puzo’s The Last Don. Its presence proves Brando was keeping up with the author, after their momentous collaboration turning Puzo’s earlier book into the role of a lifetime for Brando. According to Mann, it took the actor “a year to get through The Godfather, after which, of course, he knew it could be his comeback.”

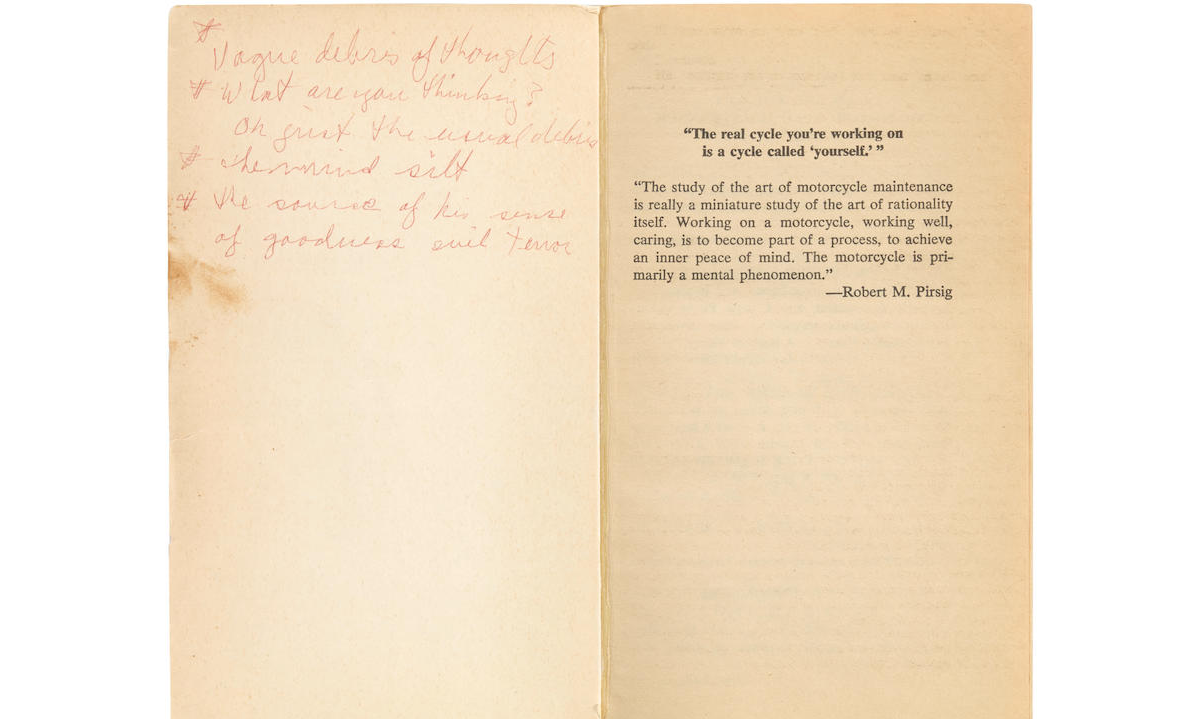

Beyond the film-related or film-adjacent books, another side of Brando emerges, as well—a philosopher and an ally. “Among the most dog-eared and annotated books [in his library] were books on philosophy, psychology and politics: Jung, Kant, Freud, Thoreau, Arendt, Rousseau, Hawking’s A Brief History of Time…,” said Mann. “More than any film role or acting award, Brando desired to understand life and the purpose of living.” At the upcoming auction, 330 books on psychology, self-help, and nutrition and 185 books on politics, law, and philosophy bear this out. Perhaps also the 75 tomes on theology and religion, or his copy of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, on the inside front cover of which he wrote, “Vague debris of thoughts . . . What are you thinking? Oh just the usual debris . . .”

He worried about fascism and racism and was involved in the civil rights movement, working with author James Baldwin on various initiatives, said Hall, while describing a collection of Baldwin materials for sale. Brando jotted notes (“Keep the story tense”) on Baldwin’s Blues for Mr. Charlie script. The author anticipated that the play, loosely based on the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, would be adapted to film with Brando’s backing, but it never got off the ground.

Brando’s collection of books on Native American and Indigenous peoples is not among those going to auction, with some exceptions, specifically one Hall mentioned as particularly poignant, found in the “presentation” lot: Where White Men Fear to Tread, the autobiography of Oglala Sioux activist Russell Means, who inscribed the book’s title page, “To Marlon – A humble man who has not taken the credit he deserves for what he has done for my People. Thank you.” Movie buffs may recall that Brando refused to accept his second Oscar in 1973, sending actress Sacheen Littlefeather in his place to protest the portrayal of Native Americans in film.

What Brando’s books ultimately demonstrate, from gardening to geography, is the man’s thirst for knowledge and his prolific mind. His books were not, on the whole, collector’s editions or decorative objects, they were true reading copies that reveal the brains behind the legendary brawn—and maybe even a piece of his heart.

Rebecca Rego Barry

Rebecca Rego Barry is the author of Rare Books Uncovered: True Stories of Fantastic Finds in Unlikely Places and the editor of Fine Books & Collections magazine. On Twitter @rrb_writer.