Honoring the Unsung History of Black and Brown Farmers

Natalie Baszile on Land Ownership, Food Justice, and Community Ties

Drive east along Interstate 80 from San Francisco toward Sacramento, past vast acres of alfalfa, watermelon, and rice, and you’ll eventually come upon a two-story mural of a solitary figure squinting out across the land. Dressed in a plaid shirt, jeans, and work boots, a tuft of gray hair peeking out beneath a baseball cap, the figure kneels in a patch of sunflowers. With one hand, the figure cradles a husky yellow Labrador.

The other hand points out to the horizon.

The figure is a farmer.

He is a middle-aged man… and he’s white.

The artist who painted the 20-by-20-foot mural titled Stewards of the Soil says that she meant to pay tribute to the farmers in her community. I don’t fault her for wanting to honor them—farming is difficult work—and I acknowledge that her mural reflects the picture most people have in mind when they envision the American farmer.

And yet, every time I drive past it, I can’t help but think it tells only part of the story. Surely, somewhere across the thousands of acres, there must be a handful of Black and brown farmers. Who are they? What stories might they tell if given a chance?

My passion for the stories of Black farmers and my interest in the related issues of land stewardship and food justice were first sparked one morning years ago when I was a student at the University of California, Berkeley. Once a month, usually on a Saturday, I bought groceries for my paternal great-uncle Lewis Baszile. He was one of the few members of my father’s family to have migrated to California from Louisiana in the 1940s, and one of only two who’d settled in San Francisco. In his early seventies by the time I enrolled in Berkeley, Uncle Lewis looked forward to my monthly visits. He was usually standing in his doorway waiting for me when I pulled up in front of his house on Lyon Street.

That particular Saturday, I was running late. Rather than shop for Uncle Lewis’s groceries at my local supermarket in Berkeley, I stopped at a supermarket a few blocks down Telegraph Avenue in Oakland. I was appalled by what I encountered. Worse than the dismal lighting and dingy tiled floor was the poor quality of the produce: a few limp bunches of collards and withering mustards, shrunken heads of cabbage, bushels of shriveled green beans, and apples and pears that were dented and bruised.

The inequity between the two markets—this one in Oakland, and my neighborhood market in Berkeley—was glaring. I was infuriated and offended. How, I wondered, could the produce in the market near campus where all the white students shopped be so bountiful while the produce in the same supermarket chain just a few blocks away where the Black people shopped be so inferior?

Back then, no one I knew spoke of food justice and food sovereignty. The term “food apartheid” wasn’t part of the lexicon. I had no outlet for my frustration, no place to express my outrage. But the memory of picking through those bins of substandard produce stuck with me.

Years later, I learned that my maternal great-great-grandfather, Mac Hall (b. 1845), arrived on one of the last slave ships and was sold twice before landing on the Stamps Plantation in Butler County, Alabama. After Emancipation he settled in the tiny rural settlement of Long Creek, near Georgiana. He was a merchant, blacksmith, beekeeper, and farmer, and eventually owned 680 acres of land thick with peach orchards. The family homeplace was only 50 miles from the Tuskegee Institute.

The inequity between the two markets—this one in Oakland, and my neighborhood market in Berkeley—was glaring.

Five of Mac Hall’s grandsons, whom everyone referred to as the Hall Brothers, learned carpentry and brick masonry at Tuskegee. Years later, they carried those skills with them when they migrated to Detroit, Michigan, where they built two-story brick houses for themselves and their family members in Royal Oak Township. Like their grandfather, they cherished their connection to the soil and understood the value in owning and taking care of land.

Their cousin, my grandfather Mamon, and his wife, Willa Mae, continued the same tradition of property ownership. They bought 11 lots around Royal Oak Township. After Mamon was killed in a car accident, Willa Mae sold the lots when she needed extra money. In the end, she sold all but one, which she kept for her vegetable garden. To this day, my mother, an avid gardener, grows collard greens in a corner of her backyard. “Staying connected to the soil,” she likes to say, “is in our DNA.”

It’s no surprise, then, that years after I graduated from Berkeley, news coverage of Black farmers converging on Washington, DC, to protest against the USDA’s discriminatory practices reignited my passion for Black farmers’ stories. I followed the proceedings of the famous class-action lawsuit Pigford v. Glickman. That passion and a growing curiosity about the lives of today’s Black farmers led me to write Queen Sugar, which is set in the sugarcane belt of South Louisiana.

In writing Queen Sugar, I wanted to tell the story of a Black farming family like the one from which I’d descended. The novel was my attempt to stop the clock, to remind readers that Black people have always had a deep connection to the land. I wanted to celebrate farming as a noble endeavor and encourage readers to continue to pass their families’ land down through generations. Queen Sugar is a declaration that Black land matters. It reminds us that if we can remember our history, we can reclaim the legacy that our ancestors fought and sacrificed for.

Today, those same passions and curiosities have led me to help preserve and celebrate the voices of the Black and brown farmers and land stewards who remain. Every week, it seems, a new article hits the newsstands sounding the alarm about Black land loss and the dwindling numbers of Black farms and landowners. I believe it’s not enough to name the problem: we must solve it.

Thankfully, hope is not lost. Black farmers continue to persevere, often in spite of the obstacles and discrimination they’ve faced. And a new generation of Black farmers and farmers of color has taken up the mantle, determined to carry us forward. They call themselves “the returning generation,” and they are fierce and unapologetic in their quest to reclaim their legacy. Like their forefathers and foremothers, they understand the value of land stewardship. They are building community and appreciate the opportunity farming provides to pursue entrepreneurship and to assert a new level of independence and sovereignty.

This country was built on the free labor of enslaved people whom carried their agriculture expertise with them when they arrived on America’s colonial shores. Black people’s labor and knowledge of agriculture built this country. Farming is part of our national identity; it is central to America’s origin story. We Are Each Other’s Harvest is my attempt to elevate Black and brown farmers’ voices and stories; to celebrate their resilience, ingenuity, and creativity; and to honor people like George Washington Carver, Fannie Lou Hamer, Booker T. Whatley, who started the Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) movement, and Booker T. Washington, who understood farming and agriculture as a path to liberation.

Plenty of Black and Indigenous people of color have devoted their lives to this movement, and they have far more experience and knowledge about farming than I do. Dozens of organizations, local and national, urban and rural, as well as activists and forward-thinking policymakers, continue to work tirelessly on behalf of Black farmers, veterans, and farmers of color.

I have tried to gather stories from a range of people—old and young, rural and urban, southerners, westerners, and northeasterners, landowners and stewards—who encourage us to remember our roots and reclaim our legacy. I could easily spend the next five years crisscrossing this country, meeting people and chronicling their experiences. Perhaps, one day, I’ll do that.

For now, as we find ourselves reeling with the devastating effects of climate change, wealth disparity, and global pandemics, it’s my hope that this work contributes to the ongoing conversation about farming, sustainability, food justice and food sovereignty, land stewardship, intergenerational wealth, and community.

I hope it shines a light on the systems that continue to rob Black and brown people of their birthright; that it encourages people of color to reclaim our legacy and reinvigorates our commitment to self-determination; that it motivates people to devise solutions to the ongoing challenges farmers face; and that it resets the narrative around labor, inspiring communities of color to reimagine what it means to be connected to the soil.

__________________________________

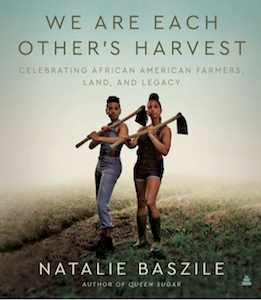

Excerpted from We Are Each Other’s Harvest: Celebrating African American Farmers, Land, and Legacy. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins. Copyright © 2021 by Natalie Baszile.

Natalie Baszile

Natalie Baszile is the author of the novel Queen Sugar, which was a San Francisco Chronicle Best Book of 2014, longlisted for the Crooks Corner Southern Book Prize, nominated for an NAACP Image Award, and adapted for television by writer/director Ava DuVernay and co-produced by Oprah Winfrey for OWN. Baszile holds a M.A. in Afro-American Studies from UCLA and is a graduate of Warren Wilson College’s MFA Program for Writers. She lives in San Francisco.