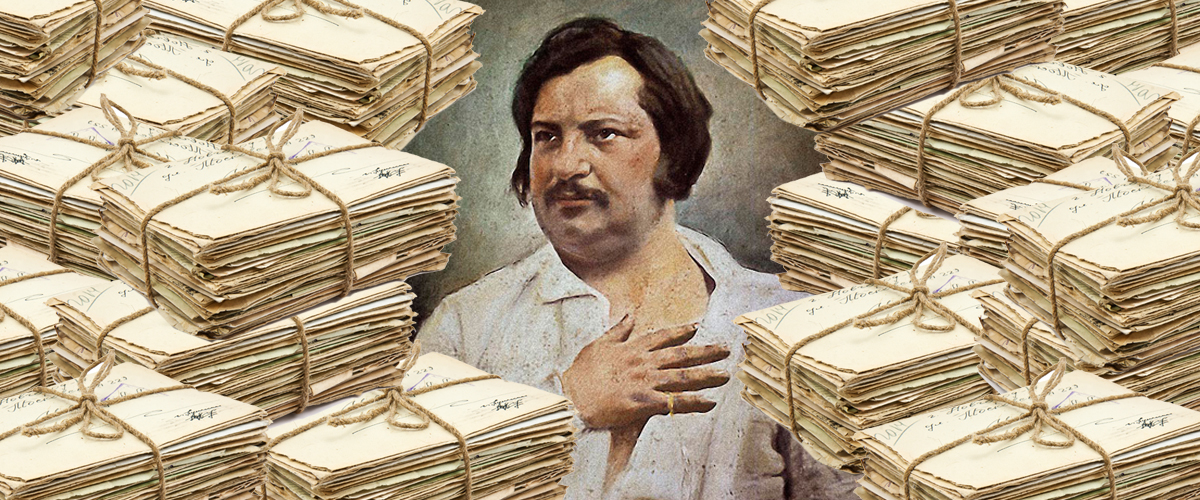

Honoré de Balzac's Legendary Love Affair With His Anonymous Critic

Or: How to Marry a Famous Writer

In March of 1832, Honoré de Balzac received a letter at his Paris address. The postmark read Odessa—then a far distant city in the Ukraine—but there was no return address.

He opened it, of course, and inside was a critique of his most recent novel, La Peau de chagrin. The letter itself has been lost to time, “which is all the more unfortunate,” writes Balzac biographer Graham Robb, “since it is easily the most important letter Balzac ever received.” But from Balzac’s eventual reply, it can be deduced that the letter derided the “cynicism and atheism” of his latest novel, and its treatment of women, who “were portrayed as evil monsters.” The letter “urged him to return to the more elevated ideas of Scènes de la Vie Privée with their angelic victims.”

The letter was signed simply “L’Étrangère” (“The Stranger” or possibly “The Foreigner”).

Moved, intrigued, and impressed—and as Robb points out, very sensitive about any charges of irreligiosity—Balzac took out a classified ad in a newspaper, the Gazette de France, hoping it might reach his anonymous critic. The April 4th issue that year ran his cryptic message:

M. de B. has received the letter that was sent to him on 28 February. He regrets that the means of replying has been withheld, and though his wishes are not of a nature that permits them to be published here, he hopes that at least his silence will be understood.

It’s not clear whether the letter writer ever saw this message, but she would write to Balzac again. Her name was Ewelina (Eveline) Hańska, a Polish countess married to a much older man, and a fan of the writer’s works. She came from a family of literary appreciation—her sister Karolina was Pushkin’s mistress, after all—and she was a major fan of Balzac’s. She was a particular fan of his portrayal of women—until La Peau de chagrin, that is. But being an educated noblewoman, she decided that she could do something about it, and so she became The Stranger.

The Stranger wrote to Balzac again in May, and multiple times that year; Madame Hańska arranged for a private courier so that they could write to one another directly, but Balzac was also obliged to provide lettres ostensibles, “dummy letters” that could make it seem as though she were corresponding with a family friend. Very early in the correspondence, Balzac was smitten. He began to fantasize about this mysterious princess. He wrote that he was “galloping through space and flying to that unknown land in which you, a stranger, live, the only member of your race. . .

I have imagined you as one of the invariably unhappy remnants of a people who were broken up and dispersed throughout this earth, perhaps exiled from heaven, but each with a language and feelings peculiar to that race and unlike those of other men.

She wrote back in similar terms:

Your soul embraces centuries, Monsieur; its philosophical concepts appear to be the fruit of long study matured by time; yet I am told that you are still young. I would like to know you, but feel that I have no need to do so. I know you through my own spiritual instinct; I picture you in my own way and feel that were I to set eyes upon you I should exclaim, ‘That is he!’ Your outward semblance probably does not reveal your brilliant imagination; you have to be moved, the sacred fire of genius has to be lit, if you are to show yourself as you really are, and you are what I feel you to be—a man superior in his knowledge of the human heart.

They continued to exchange love letters, sight unseen. They gradually learned more about one another, and though for a long time she protested that they would never meet, when she came to France with her husband in September of the year after the first letter, she couldn’t help herself. They arranged to meet in Besançon, on a promenade overlooking a lake. Neither was disappointed. According to Robb, Balzac would later say that he was “born in September 1833,” and write: “All my other passions were just a deposit for this one.”

Their affair continued, at distance, until Madame Hańska’s husband died in 1841. Even then, things were not simple, but on March 14th, 1850, they were married at last. Their happiness was short-lived—Balzac would die in August of that year. But still, the moral is clear: write to your favorite authors. You never know what might happen.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.