Hollywood’s Unlikely Evolution from The Birth of a Nation to Wokeness

Greg Garrett on Race and Racism in American Film

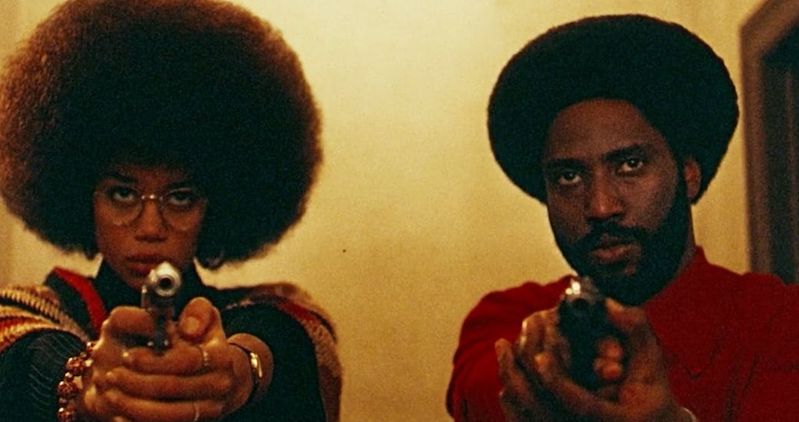

On August 10th, 2018, Spike Lee’s movie BlacKkKlansman premiered in the United States, one year after white supremacists had marched in Charlottesville, Virginia. In the climactic moments of the film, echoing the editing of D. W. Griffith, who pioneered the art of cross-cutting between story elements to build suspense, Lee moves back and forth between two scenes in which Griffith’s 1915 film The Birth of a Nation plays a pivotal role.

In one, a Ku Klux Klan initiation ceremony led by Grand Wizard David Duke (Topher Grace) is capped by an approving and enthusiastic screening of the film, which helped to create the modern Klan. In the other scene, Jerome Turner (Harry Belafonte) describes to a roomful of African American students the 1916 lynching of his friend Jesse Washington, who was burned, castrated, and tortured in front of a crowd of 16,000 people in Waco, Texas, the place where I have taught for three decades. Jerome cites The Birth of a Nation as a cause for that horrific public violence, as indeed it was.

These two scenes show how powerful a film can be in shaping or reinforcing attitudes about race, violence, and identity. “The language of the camera,” as James Baldwin tells us, “is the language of our dreams.” And, of course, our nightmares.

But in Lee’s film we also see how movies can push back against stereotypes, can speak truth to power, and can move audiences not to hate but toward understanding. Although it is set in the 1970s, in its final scenes BlacKkKlansman connects the violence and racism of the distant past and of the movie’s present with our own present (as critic Oliver Jones wrote, “Yes, this is a period movie; it’s just that the period is now, then, before and always”), and Lee reminds us that while film can carry horrible messages, it can also offer the possibility of hope.

I can hardly make credible use of the word “woke,” yet it is a crucial idea to understand in connection with our current moment.With our clear-eyed awareness that movies and other media have been a force for bigotry and hatred, we can identify and reject myths that are soul-killing and seek out myths that are soul-filling. We can watch a film; recognize elements that are racist, stereotyped, or simplistic; and hold it to account, even as we seek out stories that embrace diversity and the full humanity of every character.

In our history, as in BlacKkKlansman, race and the media are inextricably linked. Over the past century racists have used the medium of film to perpetuate harmful stereotypes and offer warped narratives, or they have portrayed white reality as though it were the only reality that mattered. A second phase followed, as white filmmakers of conscience recognized that propensity for racism and sought to make incremental changes in the stories they told. Other white storytellers launched a third phase, attempting to portray the lives of people of color in a more significant and representative way.

Later, in a fourth phase, people of color began to tell their own stories and portray their own lives, and, in a fifth phase, Hollywood films began to display a casual multiculturalism in which racial difference is taken for granted. Finally we arrive at the sixth phase, where, as in BlacKkKlansman, movies made for mainstream audiences by people of color are overturning the harmful myths of the past, denying the dangerous stories of American culture, and even turning the techniques and genres of Hollywood storytelling back upon themselves so that they become tools for awareness and reconciliation.

As a middle-aged white man, I can hardly make credible use of the word “woke,” yet it is a crucial idea to understand in connection with our current moment and the interrogation we are about to undertake. Spike Lee knows this. Before Erykah Badu, Trayvon Martin, and Black Lives Matter, his films were calling us to wake up. This call is the final line in School Daze (1988) and the opening line of Do the Right Thing (1989). It echoes throughout BlacKkKlansman.

What we will find when we investigate the hatred and bigotry, the stories and the images of one hundred years of Hollywood filmmaking, is more than just rot: It’s also a way forward.All Americans—not just African Americans—are called to be awake, to pay attention, to look through new lenses, to see what really is as opposed to what we would like to or have been encouraged to see. Another middle-aged white man, David Brooks, defined it this way: “To be woke is to be radically aware and justifiably paranoid. It is to be cognizant of the rot pervading the power structures.” Thankfully, what we will find when we investigate the hatred and bigotry, the stories and the images of one hundred years of Hollywood filmmaking, is more than just rot: It’s also a way forward.

The Atlantic writer Vann Newkirk and I were part of an onstage conversation about race, film, and healing that followed a screening of Get Out in Washington National Cathedral in February 2018. In his introduction to the film, Vann talked about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s final Sunday sermon, delivered from the cathedral’s Canterbury Pulpit just behind us:

It was in one way a standard theological examination. He begins with scripture from the book of Revelation. But then he goes to talking about the story of Rip Van Winkle, a fellow who fell asleep for 20 years and woke up—he fell asleep during the time the United States was controlled by the crown, and woke up in a post-revolutionary era.

King used that example sort of as a parable to warn people about how to remain awake during a great revolution. What he talked about was how to stay woke, as lots of people say. But also how to, if you were in the process of waking up, how to have your racial awakening, and how to get to the point where you could critically engage with life, with race, with becoming an anti-racist.

By exploring racism in American film from 1915 to the present, by exposing and rejecting the pernicious myths and embracing the good, by understanding how these films might lead (and have led) to useful conversations about race and prejudice, and by trying to become, in the process, anti-racist, we can offer correctives to Birth of a Nation in our past and to the neo-Nazis of Charlottesville in our present.

Dr. King’s goal—an America, a world, where people would be judged less on the color of their skin than on the content of their character—remains elusive. Yet it is a goal supremely worth seeking, and strangely enough, our often-racist literature and culture might be a part of our progress toward it.

__________________________________

From A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. Copyright © 2020by Greg Garrett and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.