Hiroshima at Eighty: Contemporary Literature as a Product of the Post-Nuclear World

Ed Simon Considers the Enduring Impact of the Atomic Bomb on Artistic and Literary Production

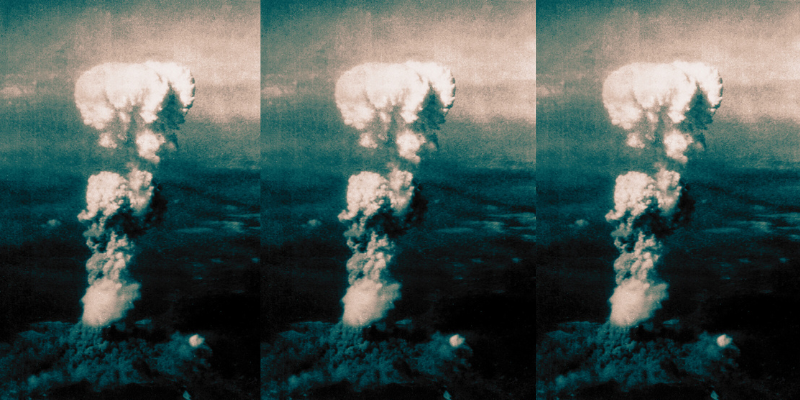

At exactly a quarter after 8 on the morning of August 6, 1945 the device named “Little Man” was dropped from the Enola Gay. Only a kilogram of the bomb’s 64 kilograms of uranium underwent nuclear fission, but that was enough that when it detonated 2,000 feet above the ground it released the equivalent of fifteen kilotons of TNT with a blast radius of nearly a mile; 80,000 people in Hiroshima were instantly killed, nearly double that number died in the next few days.

There have long been tales of cities instantaneously destroyed by some divine wrath, such as the angry Divinity of the Hebrew Scriptures raining sulfur upon Sodom and Gomorrah, but in Hiroshima humanity had finally apotheosized itself into the terrible position of God. In the ancient Hindu scripture the Mahabharata, there was a weapon called the Brahmastra capable of leveling entire cities in plumes of smoke and flame, leaving behind only soot and cinder. This “single projectile/charged with all the power of the Universe…bright as ten thousand suns…as if the elements had been unleashed.” Similarly—“Such clouds of dust had risen that there was a sort of twilight around,” except that’s not the Mahabharata, but rather The New Yorker correspondent John Hersey’s 1946 account Hiroshima.

All of contemporary literature is atomic bomb literature because all of it is written in the reality of our borrowed time in the nuclear age.

Two-and-a-half millennia after scribes imagined such devastation in Sanskrit verse transcribed onto palm leaves, humanity hadn’t just unfrozen matter into pure energy, but had transformed myth into reality. All of time separates into before and after that moment. A spot of air some 800 feet above the ground and between the Honkawa and Motoyasu Rivers is our Golgotha, the site where history cleaves into two. Some 525 feet from where Little Man exploded was the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, an exhibition space of steel and concrete which opened three decades earlier and was of such stolid construction that even after the atomic bomb incinerated nearly everything within its hypocenter, the red-rusted twisted skeleton of the building’s domed roof still rose over that city of ash and shadows.

The renamed Atom Bomb Dome still stands as part of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, the crumbling ruins a testament to the only nuclear war (so far). Having visited the dome myself, the clearest impression that stays with me is how Hiroshima isn’t just surprisingly pleasant, but beautiful. A grassy expanse between two rivers framed by the prefecture’s hills in the distance, so that when I visited twenty years ago it strangely reminded me of my hometown of Pittsburgh, though of course the buildings are all much newer.

There is nothing prosaic about the park, because even while it may seem (and is) a perfectly lovely place to enjoy lunch with your family or to perhaps steal a few minutes to read on a bench, the presence of so much death and suffering is inescapable. Locations can be haunted; our witnessing often requires it. And so when silently walking past the Atom Bomb Dome, or the elegant Peace Bell, the moving Flame of Peace, the heartbreaking Children’s Peace Monument, or the somber Peace Memorial Museum it is impossible—must remain impossible—to forget that at this spot women and men—innocent civilians—were sacrificed in a moment of inconceivable hubris. A place were humans suffered in inconceivable ways in the following weeks as the bomb itself seemed to pull upward from the firmament hell itself. If sacred means separate, outside of the prosaic flux of things, then this Japanese city is sacred. Hiroshima is the modern world’s Axis Mundi, its Calvary, its moment of divine contact, where we discovered that the only God and Devil which exists is us. The atom bomb was the hot force which secularized Armageddon.

Even if the singular moment in which apocalyptic fire was first grasped by human hands occurred at the evocatively-named Trinity Test Site in Alamogordo, New Mexio three weeks before August 6, it wasn’t until Hiroshima and the second bombing at Nagasaki three days later that the world was introduced the Manhattan Project’s implications. The construction of the bomb is itself a great American tragedy, this assortment of brilliant physicists gathered in the desert primeval to unlock the mysteries of creation in the furtherance of destroying part of that creation. That most were working on the project for objectively noble reasons in a war against authoritarianism only compounds the tragedy. A figure like J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the project, becomes as mythic as if he were Prometheus and Pandora, Frankenstein and Faustus. Just as the heat of Trinity forged sand into glass, that same device (and all after it) transubstantiated myth into reality. Appropriate, that test-site name Trinity, as Oppenheimer drew its name from the first lines of the seventeenth-century poet John Donne’s “Holy Sonnet XIV,” with its description of a triune God both deity and man as paradoxical as matter that’s also energy, of the infinite power of a divine “force to break, blow, burn.”

Some major shifts happen subtly. Hiroshima was not like that, even if we’re still trying to comprehend that event. President Harry Truman, whose decision it was to drop the bomb, bragged in a speech sixteen hours after the explosion that its strength came from “a harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its power has been loosed against those who brought war to the Far East,” even if the force from which the sun draws its power is actually nuclear fusion, not fission, and the hydrogen bomb which deploys that phenomenon wouldn’t be first tested until 1952. However, the emotional tenor, bombastic and triumphalist as it may be, still holds—that humanity had achieved the alchemical dream, that mass had been converted into pure energy with inconceivably powerful results. While Truman thought the bomb was the greatest thing in history, Albert Camus offered a more somber and astute observation in an August 8 editorial for the French newspaper Combat, noting that “technological civilization has just reached its final degree of savagery.”

Literature—the foundational art—would react to the electromagnetic pulse and the haze of the mushroom cloud, for how couldn’t it? The initial treatments were eyewitness accounts, for journalism is literature’s first draft as much as that of history. I’d claim that poetry can be the most salient form of genuine journalism. Poet Sankichi Toge, a hibakusha, which is to say a survivor of the explosion, describes his experience in the 1951 collection Poems of the Atomic Bomb, how in the rubble the “shrieks of the 50,000 died out,” how he witnessed a “line of naked bodies walking in groups, crying/with skin hanging down like rags/hands on chests/stamping on crumbled brain matter” or the horrific scene of a “group of high-school girls/who had fled and were lying/on the floor of the armory, in excrement/their bellies swollen, one eye crushed, half their bodies raw flesh with skin ripped/off, hairless, impossible to tell who was who,” the long, uninterrupted lines methodically describing the horrors that he’s seen. Tamiki Hara was 39 when he survived the bombing; his 1947 essay “Summer Flower” inaugurated the genre of genbaku bungaku, that is “atomic bomb literature” penned by hibakusha. Hara includes in the essay a poem in all capital-letters which he penned on August 6 after surveying the wasteland, of the “BROKEN PIECES, GLITTERING,/AND GRAY-WHITE CINDERS,/A VAST PANORAMA – /THE STRANGE RHYTHM OF HUMAN CORPSES BURNED RED…THE UNIVERSE HENCEFORTH, STRIPPED IN A FLASH OF EVERYTHING.” In their testimony, such writers presented a vision more horrific than all of the grandiloquence of Dante or Milton, even of the Mahabharata, for they offered simple truth. “WAS ALL THIS REAL? COULD IT BE REAL?” Hara asked.

Eyewitness accounts were as if a portal into an undeserved hell. Even while the firebombing of Tokyo took more lives than were lost in that instant in Hiroshima, it’s that word “instant” which makes a difference. Here was the detonation of the Brahmastra, of something as mythological as scientific, which is why all of us born after 1945 grew up in an entirely different dimension than those born before. As of today, there are an estimated 12,241 nuclear weapons spread across several different regimes. The most powerful is Russia’s Tsar Bomb at fifty megatons, some 3,333 times more powerful than Little Man. We all exist under a nuclear Sword of Damocles, forever threatened by the whims of mad leaders or incompetent computers (and several times the world has come close to apocalypse for reasons of dizzying stupidity). If there is a narrative logic to nuclear weapons it’s something that Chekhov could explain well—if a gun is introduced in the first act, you can expect that it will go off by the last. An execution date does have the benefit of focusing the mind, however. In the twilight of the nuclear age wherein humanity’s extinction is always threatened, every expression takes on infinite importance for every expression could be our last.

Faced with this New Nihilism, some artists (?) have opted for expressive absurdity, from the trauma response of the brilliant Japanese “Godzilla” film franchise to the deep-fried Americana strangeness of Cold War gospel tunes like the Soul Stirrer’s 1950 “Jesus Hits Like an Atom Bomb.” There are quieter, prophetic voices as well, of poet Toi Derricotte from her 1989 collection Captivity with her premonitions of the “instant/before destruction, /the fiery storm stuck/as if under the control of the artist/before it spilled and became irretrievable” or of Bob Dylan in 1963 singing “a hard rains a-gonna fall.” Ultimately, however, all literature written after 1945 is atomic bomb literature, and not just Martin Booth’s sobering account in Hiroshima Joe or Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic parable The Road, Walter Miller’s sci-fi classic A Canticle for Leibowitz or hibakusha writer Ota Yoko’s City of Corpses. All of contemporary literature is atomic bomb literature because all of it is written in the reality of our borrowed time in the nuclear age.

Poetry is impossible because its posterity is sacrificed on the altar of inevitability. Though at the moment, well, poetry isn’t only possible but required.

“What we cannot speak of, we must pass over in silence” wrote the Great War veteran philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in 1921, and maybe that explains the failure of not just all writing that pretends to understand the nature of the bomb, but indeed of all writing after the bomb. It’s not commensurate with the singularity of what Hiroshima both represents and portends. The greatest poetry of the devastation might simply be silence; of Toge describing “that silence…that stillness/the powerful appeal.” Everyone who knows anything about the Manhattan Project has heard Oppenheimer’s self-serving erudition in repeating the line from the “Bhagavad-Gita” (a portion of the Mahabharata) where Krishna says “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” but a far more potent expression of the meaning of the bomb’s first test is recounted in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, wherein the physicist Richard Feynman explained that as he was positioned miles from Trinity he had tuned his radio to a New Mexico classical radio station and listened to arias as he awaited the blindingly-bright flash of light, momentarily shocked by the silence of the atom bomb until its roar caught up to him and drowned out the music.

The German philosopher Theodor Adorno, in a line almost as famous as Oppenheimer’s, is often misquoted as saying that “After Auschwitz poetry is impossible.” Adorno’s contested observation may be true (so too Oppenheimer’s), but I’d amend the sentiment to add that poetry is also impossible after Hiroshima. Poetry is impossible because its posterity is sacrificed on the altar of inevitability. Though at the moment, well, poetry isn’t only possible but required. For the paradox is that the impossibility of poetry is what makes it all the more imperative to write it. That is the demonstration of hibakusha poet Sadako Kurihara in her August 1945 “Bringing Forth New Life,” with its description of a mother in labor amidst the ruins of Hiroshima. Surrounded by broken concrete and rebar, “Victims of the atomic bomb jammed the room…The smell of fresh blood, the stench of death, /the closeness of sweaty people, the moans.” Yet in the middle of “that hellish basement, /At that very moment, a young woman had gone into labor.”

Kurihara describes how regardless of all the horror and pain, the suffering and torment that all those who were assembled had already experienced in the past few days, the collective concern of the basement turns towards the expecting mother. A midwife named Umeyo Miyoshi announced herself, she is “seriously injured” and “moaning only moments before,” but nonetheless delivers the child. “And so new life was born in the dark of that pit of hell,” writes Kurihara, “And so the midwife died before dawn, still bathed in blood.” Where is meaning to be found after 1945? In the eerie silence and sacred light as we look west towards the burning clouds on the horizon? Or in the cries of that newborn child? “Let us be midwives!” answers Kurihara. “Even if we lay down our own lives to do so!” Kazuko Kojima, the child who inspired that poem, still lives in Hiroshima and her 80 birthday is this month.

Ed Simon

Ed Simon is the Public Humanities Special Faculty in the English Department of Carnegie Mellon University, a staff writer for Lit Hub, and the editor of Belt Magazine. His most recent book is Devil's Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain, the first comprehensive, popular account of that subject.