Hideous Shakespeare: On Courting Ugliness in Portraiture

Lee Durkee Considers the Many Painted Portrayals of the Bard

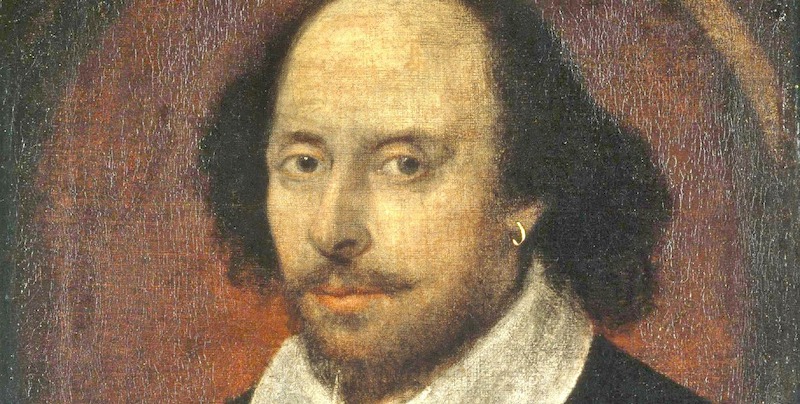

Regarding the portraits said to depict the late Mr. Shakespeare, there are good reasons to be cynical. You could, after all, crowd the snail-shell Guggenheim with the four-hundred-year parade of counterfeit bards, each one prettier than the last, evolving Will by Will like some Darwinian ascent from the knuckle-dragging Droeshout engraving of 1623 to the superciliously upright Cobbe portrait recently embraced by the town of Stratford.

Invariably the sagas of these painted poets have been tragic in nature, each in turn girded in gold, basked in bulbs, then whisked upon the shoulders of a scholar’s reputation through London, New York, and Milan… only to find itself a short while later a laughingstock: debunked, denuded, holed up in a seedy motel, and eventually hung upon the wall of some dungeon museum as a curiosity, a cautionary tale, a freak show. Meanwhile a prettier yet Shakespeare, one with Fabio hair and a fly leather doublet, is hoisted aloft by the adoring crowd.

Throughout humanity’s centuries-old search for Shakespeare ad vivum, a picture painted from life—one he sat for, one he paid for—no candidate portrait, however celebrated, has withstood the test of time. For the most part, Shakespeare ad vivum has been a history of artistic con men and starry-eyed scholars.

During the eighteen years, following a divorce, that I was forced to live in arctic Vermont, I found myself readdicted to this search every winter. And Shakespeare ad vivum is in many ways a wonderful winter addiction, an unsolvable puzzle that constantly makes you feel as if you are about to conquer it. But nobody ever has.

I couldn’t help but wonder what scandals and heresies might lurk beneath four hundred years of overpaint.

So welcome to the Shakespeare Funhouse, where four centuries of frauds stare out at you from inside warped mirrors. A bit dizzied and intimidated, I reminded myself I had one big advantage over the countless academics who had failed in this search. At the time I began my hobby, museums had just started creating virtual galleries online. These galleries often displayed portraits that had been hidden inside storehouses for decades or even centuries.

During the day I inventoried the facial anomalies unique to Will Shakespeare and began to master software capable of comparing these anomalies. At night I put on my black mask and became a virtual art thief who had taught himself to disassemble, steal, and then sew back together high-resolution portrait jpegs from online museums.

But how, I wondered (as I turned dazed circles), was a novice like myself to decide which portraits to begin investigating? Following some discouragement, I soon hit upon a strategy, a path less taken I hoped might lead me to my hero. Since it seemed obvious Shakespeare had been getting prettier by the century, I decided to ignore those boy-toy bards so popular with modern scholars and home in on the more neglected candidate portraits, the wretched-refuse Shakespeares, the homeless, homely, and tempest-tossed mutts nobody wanted to depict our Soul of the Ages.

This decision seemed logical in that the Droeshout engraving from the 1623 First Folio, our one avouched likeness, had revealed a poet burdened with an encephalitic head containing two froglike eyes swollen, it has been suggested, by the blossoming of syphilis. Why look for such a Jack among the jet set?

And so I went to work. Any portrait that interested me—the uglier the better—got bookmarked and filed. My court favorites were special ordered or torn out of books. Soon I started paying museums to photograph obscure portraits. As the bills piled up, I began papering the walls of my Vermont fishing camp with the mug-shot bards only a mother could love. (Trust me, my Shakespeares can beat up your Shakespeares.) In the depths of my despair with seasonal depression, these mangled poets consoled and befriended me, and eventually, usually around the third blizzard of March, their eyes began to follow me as I paced my office devising and discarding some very peculiar theories about William Shakespeare.

There was more to my strategy, however, than courting ugliness. Every winter I became more fascinated with the technologies that allow us to time travel back through layers of paint. To that purpose, I became adept at pestering curators into plumbing their would-be Shakespeares with spectral technologies. And by spectral technology, I mean the black magic of infrared reflectography, which fires an IR beam through paint layers until it is absorbed by any carbon-based underdrawings; X-ray examination, which thrusts electromagnetic light up through the paint layers and imprints their history onto a radiographic film thereby exposing underportraits, extirpations, retouchings, and counterfeitings; dendrochronology tests wood panels to establish the general age of a portrait’s backing; pigment analysis can determine original color, establish date of composition, and help identify the artist; raking light angles a beam across the portrait’s surface to reveal an ocean pitch of texture; and ultraviolet examination uses black light to darken both new paint and old varnish while making the whole portrait resemble a haunted house caught in a lightning storm.

My hope was that these technologies might help me discover not just what Shakespeare had looked like but who he had been. Censorship of all art forms ran rife throughout both Elizabethan and Jacobean England, and I couldn’t help but wonder what scandals and heresies might lurk beneath four hundred years of overpaint.

Inside that frozen landscape the disgruntled portraits of Will Shakespeare befriended and bewitched me.

We tend to project our own culture backward onto history and paint ourselves over dead tribes, but in approaching Shakespeare’s generation of wits and writers, it’s important to recall they were much smarter than we are—and far more conceited and ruthless. They employed spatial memory systems that allowed them to access entire libraries of inner guile. Vainglorious, superstitious, and hyper-paranoid, they lived among ghosts, demons, poisons, codes, witches, spies, pen names, and plagues.

They were obsessed with bloodlines and caste systems, but perhaps their most defining characteristic was a fear of death, or oblivion, so chronic it gave birth to an insatiable thirst for fame—and not just any fame, but the eternally flickering candle called immortality. To this purpose, portrait painting became an Elizabethan fetish so in demand it jumped the caste system to spread from the nobility down into the upstart merchant class.

As to my own motives for joining this ancient search for a lost portrait, I doubt you should trust any explanation I offer. Sure, my admiration for the Elizabethans had a lot to do with my fixation. They’d forged the language we use to think with, and in that sense they were our creator gods. But I had some unsavory motives as well. I, too, pined for immortality, however jaded, and longed to be whisked away from my bartending job to London, New York, and Milan—or, for that matter, any place warmer than the state of Vermont, where I had promised myself I would stay until my son was old enough for college.

When I began this intermittent project, I vowed to approach it with no preconceived notions. Let the bard cards fall as they may, I said. I had studied the Elizabethans for decades, and the more I’d learned about this eccentric tribe, the less I felt I knew about Will Shakespeare. During my search I’d had him in my grasp any number of times, had my hands wrung around his ruffled neck, but he kept changing shapes, tricking me, and slipping away. He was Ovidian: a white rabbit, a murdered spy, a decadent earl, a castaway actor, an infinity of typing monkeys…

It’s not a pretty story what follows, but it’s an honest one. Although my years of exploration have produced a tale filled with sorcerers, demonic possession, royal scandals, portrait switchery, Adderall addiction, incest, madness, ghosts, shark tanks, and two sordid murders, that was not my intent. What started off as a dilettante’s hobby took over my life during those endless winters I could not abide. Inside that frozen landscape the disgruntled portraits of Will Shakespeare befriended and bewitched me. My research became something magical and demented, intuitive and haunted. In the end it changed the way I look at history, art, politics, and myself. It certainly changed the way I look at William Shakespeare.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Stalking Shakespeare: A Memoir of Madness, Murder, and My Search for the Poet Beneath the Paint by Lee Durkee is available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Lee Durkee

Lee Durkee is the author of The Last Taxi Driver, named a Kirkus Reviews Best Novel of 2021, Rides of the Midway, and Stalking Shakespeare. His stories and essays have appeared in Harper's, The Sun, Oxford American, Zoetrope: All Story, and Mississippi Noir. He lives in Oxford, Mississippi.