Here's the World's First Public Gallery of Modern Art

Hugh Lane and the Art Gallery as Theater

Born in Ireland in 1875, the art dealer Hugh Lane died aged only 40 when German torpedoes sunk the Lusitania. In between, with little formal education and scant training, he orchestrated high-profile sales of paintings by Titian, Holbein, and Velasquez, among others, as he assembled collections for a Municipal Gallery of Modern Art in Dublin, the Johannesburg Art Gallery, and a collection of Dutch paintings for Cape Town in 1913. Not long before his death he had been appointed Director of the National Gallery of Ireland. His career suggests the singular way that an art dealer might shape the early phases of an art museum at the beginning of the 20th century and the diverse meanings that can accrue to works of art in local, national, and global contexts.

Lane’s Municipal Gallery of Modern Art (which opened in 1908) was an ambitious and groundbreaking institution—the first public gallery of modern art in the world. Lane’s aspirations in founding it were many and often conflicting. One of my favorite recollections of him, by the artist Henry Tonks, declares: “He did not care twopence if people came in to see his pictures, he would be quite content if they came in to keep themselves warm.” Although many critics have described the funereal association of museums as the place where culture goes to die, Lane believed were vital cultural entities. They presented important examples of beauty and cultural achievement that provided education, inspiration, and enjoyment for a general public. He was preoccupied with every aspect of the installation and decoration of the galleries, from the placement of the paintings to the arrangement of furniture and flowers.

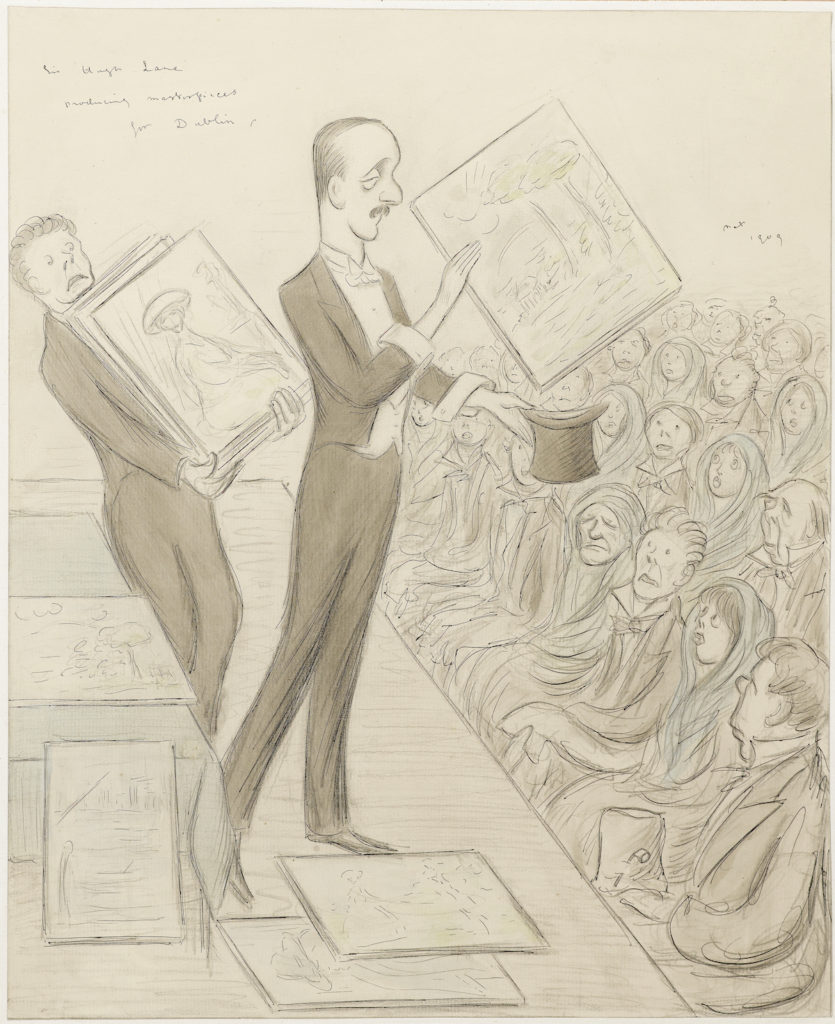

Max Beerbohm, Sir Hugh Lane Producing Masterpieces for Dublin, 1909. Ink and pencil on paper, 43.7 x 37.3 cm. Dublin City Gallery, The Hugh Lane.

Max Beerbohm, Sir Hugh Lane Producing Masterpieces for Dublin, 1909. Ink and pencil on paper, 43.7 x 37.3 cm. Dublin City Gallery, The Hugh Lane.

Later, he compared the “setting” of a gallery to theatrical scenery, complaining to his aunt that the Abbey Theatre, her venture with the poet W. B. Yeats, didn’t pay enough attention to scenery and costumes. Whereas in his gallery, “the importance of a proper setting is quite as important as the pictures.” Lane planned to display his collection of modern art amidst a decorative program of scenes from Irish legend. By doing so, he positioned his French Impressionist pictures as part of a decorative tradition that included Celtic art, thus fusing them to an Irish identity in unexpected ways. In particular, he declared his hope that the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art would nurture “a distinct school of painting in Ireland.”

The public response to the gallery was mixed: while some praised Lane’s gift, and his selection of paintings, others puzzled over the nature and meaning of this new institution. All of works in the gallery (285 of them) were gifts or promised gifts from Lane as well as artists and other benefactors. The best-known group, the French Impressionist paintings purchased by Lane, were part of a group of 39 works known as “the conditional gift,” to be given to the city once they established a permanent home for the collection.

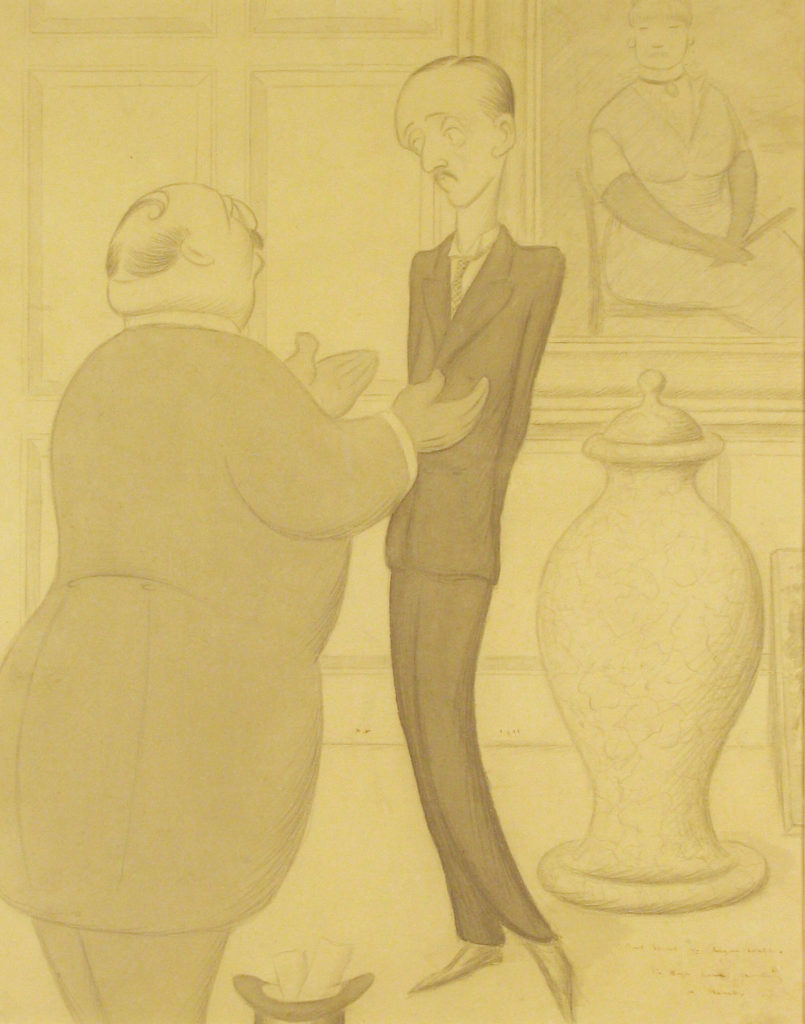

Max Beerbohm, Bond Street v. Cheyne Walk: Sir Hugh Lane Guarding a Manet, 1911. Pencil on paper, 41.1 x 32.8 cm. Dublin City Gallery, The Hugh Lane.

Max Beerbohm, Bond Street v. Cheyne Walk: Sir Hugh Lane Guarding a Manet, 1911. Pencil on paper, 41.1 x 32.8 cm. Dublin City Gallery, The Hugh Lane.

As caricatured by Max Beerbohm in 1909, the connoisseur Lane was a kind of magician, pulling Manets and Monets out of a hat. This trick baffles his Irish audience, who appear both rural and provincial. They are either wide-eyed with horror or stoically unimpressed. Beerbohm intuits the complaints of Lane’s critics, who suggested that Ireland was not prepared culturally or socially for modern art and that public money was better spent addressing issues of sanitation, for example, or public housing.

His success in Dublin brought him to the attention of Lady Florence Phillips, whose husband had banking and mining interests in South Africa, and she asked Lane to assemble a collection of modern British and French art for the Johannesburg Art Gallery in 1910. The collection of modern art would articulate South Africa’s relationship to the British Empire in both local and global contexts in the decade after the Second South African War (1899-1902). With his work in Johannesburg complete, he turned his attention to assembling a gallery of 17th-century Dutch art that would unite Boer and Briton through “the representation of the art in which the Dutch and English first met in spirit.” Lane’s museums were supposed to heal the wounds of war by drawing upon notions of a shared cultural heritage amongst the white populations of South Africa. Yet Lane and his donors clashed over the paintings and the prices.

In his life and work, Lane acknowledged the volatility of the collection in relation to both the art museum and the art market: works of art may come and go from both the sale room and the museum walls. Yet his actions affirmed the ideal of the art museum: art is worthy of display for the benefit, enjoyment, and education of the public.

*

A screening of the film Citizen Lane, followed by comments by Dr. Morna O’Neill, will take place at the Frick Collection in New York at Tuesday, May 7, 2019, starting at 5:00 p.m. Tickets may be purchased here.

Morna O'Neill

Morna O’Neill is associate professor of art history at Wake Forest University. Her book Hugh Lane: The Art Market and the Art Museum, 1893–1915 is published by Yale University Press in association with the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.