“Here is What I Know: A Baby is Born.” On the Wild West of Childbirth.

Erica Stern Considers a Traumatic Birth and the Many That Came Before

Ten centimeters, Dr. G. announces triumphantly. She’s back in the room. She means I’m fully dilated, that my body has released enough oxytocin to cause my uterus to shudder and squeeze my baby’s head down, drill against cervix, so it opens wide enough to expel the infant. The complex mechanics of an organic Rube Goldberg machine.

Jed rises, his eyes suddenly wide open and alert. He dusts his hands on the thighs of his jeans, ready to jump the threshold into parenthood. I’m still lying flat in the bed, feet stirruped.

Dr. G. tells us she will call a pediatric team into the room for delivery because of the thick meconium-stained liquor from the water breaking that never ends. Liquor. It sounds luxurious, velvet, baby swaddled in moonshine, opaque and rich and dizzying, instead of what I know meconium to be—an infant’s first bowel movement, sticky and putrid and green.

It’s our protocol, she explains, detaching the delivery bed bottom in preparation for the end. So Baby doesn’t aspirate the mec into the lungs. You won’t be able to hold Baby at first, she says. They’ll need to suction the liquor so it isn’t inhaled deep into the lungs.

Mec is short for meconium, but no one bothers to translate. Dr. G. fumbles inside one of the bins brimming with metal tools. Baby won’t cry right away. In fact, we don’t want Baby to cry until suctioning is complete and the mec cleared from its airway. It will only take a minute but that minute will seem like an eternity, she warns.

Ok, I say.

Ok, Jed says.

Do not be alarmed, she says. After they’re done, the pediatricians will hand Baby back over to you. She enters something into the computer. Do not be alarmed.

Baby, the medical staff all say, lopping off the article. It’s simply Baby. Baby seems more comfortable in this position. Baby is in no hurry to get out. Baby is giving us a run for our money. The hospital morphs baby into a proper noun and, in doing so, quasi-anthropomorphizes it—human, sure, but on the cusp. Its stance towards the parents is strangely infantilizing, echoing the way a preschool teacher speaks to her charges. As though the mother (or Mama, as the staff like to call me, and I presume other laboring women) needs things fed to her, bite-sized and deposited directly in her mouth).

Baby can’t handle too much, she says, of the pushing. I don’t know what this means but there is a lot I don’t understand. More than I can ask about while my body heaves.

Prepare ye the way of the Lord, goes the opening song of Godspell. And that’s it. Prepare ye the way of the Lord. Prepare ye the way of the Lord. Prepare ye the way of the Lord. The chorus jumped side to side and waved their hands overhead. I’d never before felt so much a part of something. The me faded into the collective.

I push for two hours, but it might be two minutes or two days. I’m a factory worker in charge of a switch. The final nurse, plain face and plain name, studies a tracing of my contractions and tells me when to bear down, when to ease up.

1,2,3, go, she chants.

She knows more of my body than I do. The anesthesiologist returns and lowers the epidural dose so I can feel something (pressure, not pain, he is careful to distinguish, like those male doctors of history, with curious insight into the birthing body). It’s important that I am able to sense my muscles squeeze the baby so I can use this feeling to propel and amplify my efforts. Jed stands next to me, sidelined; he cannot read the monitors and cannot feel the tightening. I know I push for two hours because Dr. G. says, I’ll let you push for two hours, but that’s the limit—like I’ve begged for time and we’ve reached this deal after tense, drawn-out negotiation. Baby can’t handle too much, she says, of the pushing. I don’t know what this means but there is a lot I don’t understand. More than I can ask about while my body heaves.

So that I could better understand the plot of Godspell, my mom bought me a book about Jesus at The Catholic Bookstore, a converted bungalow situated on an oak-lined avenue. I knew understanding was important to acting. An actor had to turn part of himself into the character in order to convince the audience, and this was only possible with knowledge.

From the book I learned real Jesus was human, born to a woman in a manger, but also god. Similarly, his death was preordained and necessary for salvation, but also mourned. The contradictions didn’t bother me. Childhood might be defined as the state of holding many truths at once. Aging occurs when that simultaneity breaks down and we must pick one or the other.

Pregnancy is another sort of breaking down, taking the self apart to create another. Puking into the toilet in my first trimester, I felt the detritus left behind from that cleaving exit my body. I felt it flowing up my throat, through my lips. I was purging the mess out to make room for what was next.

Between pushes, the nurse slips the soaked green sheet out from under me, slaps down a clean one. Single fluid motion, easy to miss.

1, 2, 3, go.

Somewhere out of sight—hidden from monitors and hovering nurses and Jed and me—a tightening. A narrowing. Almost pastoral, rapids slow to a serene trickle over moss-covered rocks. The flow restricts and, for a moment, time grinds to a halt. Here in the delivery room, the blood pressure cuff squeezes my arm every few minutes. After a while I barely register the compression. When it’s done, the cuff releases with an audible sigh.

I was not a nester—one of those pregnant women who delight in placing chevron decals in rows along the nursery walls and stacking baby blankets just so in the closet. Perhaps this was the result of absorbing lingering Jewish superstition: babies aren’t a thing to be counted on until birth. Or maybe it pointed to insufficient investment in this internal creature who I didn’t believe would become my baby until I held it and it cried.

Instead of nesting, I broke down in the aisle of the baby store. How could they name the store something as crass as BuyBuy Baby? I wanted to know. There were too many gliders to choose from and they all cost too much. I couldn’t figure out if I was offended by the materialism or overwhelmed by my inability to navigate the storm of supplies.

We don’t need any of this stuff, Jed argued. But I was less convinced. On the shelves: special scarves for breastfeeding privacy, specialty nail clippers that wouldn’t fissure skin, pulse ox monitors with cutesy names designed to detect danger in the night, bottles with inserts to ease digestion, fitted car seat covers for snow and rain and shades for summer and swaddle blankets made out of muslin and cotton and fleece to keep babies at exactly the right temperature. Every item facilitating a happy, healthy baby. We couldn’t buy it all even if we wanted to, not on a grad student and law clerk budget. Besides, we didn’t need it all. If only I knew how to distinguish between needed and not.

Without realizing it, I’d bought into the hype. I saw the images of the happy babies smiling at their tired, happy moms (or well-rested actors pretending to be tired, happy moms) on the boxes of video monitors promising that I could watch my infant on static-free screen as I luxuriated in the comfort of my own bed. Even as I bucked against the idea that I needed an expensive tool to provide postpartum bliss, I couldn’t help but see my future self in that model mother, open arms awaiting my future baby brought out from the hidden crevice of the womb. At the OB’s, I trusted the various blood tests and ultrasounds that indicated a healthy baby and didn’t think about the fact that there were hundreds or thousands of conditions sitting outside the purview of these diagnostics.

All of it—the Nose Frida contraption straight out of more evolved Scandinavia and promising efficient snot removal from a congested infant, and the clear first-trimester screen designed to detect genetic diseases— affirming my naïve assumption that progress and technology had gotten women to a place of perfection. We don’t die in childbirth anymore, I thought, imagining with a shudder what it would be like to approach one’s due date like a coin toss that would determine life or death. Now babies arrive healthy—rosy and rooting. I assumed we’d moved above and beyond, outside of risk and danger, ascended to a higher plane. In my cocoon, perhaps aided and abetted by the fact of my whiteness, I conveniently ignored how recently history had removed women from this grave threat, and how the danger still, sometimes, lurked.

I’m splitting faster and faster, breaking down into something I don’t recognize, something older, some other past version of myself, spinning backward, inchoate.

Okay, Dr. G. says. My two hours are up, alarm gone off. She removes her oatmeal-colored sweater to reveal green scrubs, holds up bright silver forceps. Imagine sterile salad tongs, she says, as though alluding to the crochet hook she used to break my water. But the water didn’t come out clear as I was promised by the movies, and this new instrument is too strange and medieval for domestic metaphor. Some of the room’s arms emerge from the walls and ceiling. Lights brighten. More doctors and nurses converge as if they’d been crouched, hiding alongside the arms the whole time. This is the pediatric team, Dr G. says, pointing in one direction. And here is anesthesiology. And there are the OB residents and fellows and nurses. I don’t care about introductions. Too many faces to track. Some wait on the periphery like a chorus; others crowd in, closer. One last push, the doctor says. Jed tightens his grip on my hand. For an instant, all I smell is his almost-worn-off Old Spice instead of the cold astringency of the hospital. I’m back home, in bed next to him in our apartment.

Physician Peter Chamberlen developed forceps in the seventeenth century, when doctors began to encroach on the work of midwives, stomping their way into the most feminine of domains. Chamberlen’s forceps were novel because they did not necessarily kill the fetus. Until then, tools for delivery, sometimes cooking implements snatched from kitchen drawers, cleaved the baby—impossible to save both mother and child. After all this time sharing one body, their lives were at odds. Hooks tore off limbs and devices pierced skulls and extracted brains. Sometimes, one hopes, the baby died before this dismantling. If the fetus was to be saved over the mother, if she was too far gone, then the baby would be delivered by cesarean section instead; women weren’t expected to survive the procedure. In old sketches of the varieties of forceps, they resemble rabbits with large ears.

Let go, the yoga instructor demanded, as we released our bodies into child’s pose, hands stretched out on the mat. Here, in the delivery room, I’m ready to let go, if only my body will let me.

1, 2, 3, go the nurse chants as the line of my contraction rises on the screen and her hands rise with it and I take in a deep breath until it throbs all over my body not from the contraction which is faded and worn and more ghost than muscle but from holding it all in and the prongs are deep inside pulling pulling pulling and then the counting is at 8, 9, and I only hear parts of things because we are all shimmering like breath in cold air and the nurse says let go and when I do my neck merges with my arms my eyes with my knees my liver with my heart my stomach with the metal inside nothing solid nothing distinct I might lose myself over the edge and I don’t know if I do it or if forceps finish the work.

Jed says: Its head is a funny shape. It’s strange looking. Not like a baby. He inches away from it. Is it over?

I am not in the bed. A body lies on the bed. I am not contained in the body. I must be stuck in the vent above the room, looking down. I do not know how I got there: shrunken, hiding. Things happen to a body that, at some point, was mine, but I am not part of what happens to it. I’m stitching you up, the doctor says to the body. The body can hear the words but cannot understand them. Your tear isn’t too bad for a forceps delivery. Tear? What tear?

What about the placenta? I ask from above. I remember this part from the hospital’s labor and delivery class; it’s not over once the baby emerges. Also, from a TV show where a chunk of the ruby red temporary organ sticks to a woman’s insides, bleeds, until a midwife reaches her arm up and up, a plumber’s auger, and dislodges the stubborn part.

Already out, the doctor says. The body feels a faint tug. From the vent I see edges of things: feet shuffling, lights brightening, carts wheeling, tubes and wires stretching. They should make noise but don’t. It’s strangely quiet. Not silent but someone has turned the volume down to 2 or 3 out of 100. I strain to hear.

What’s happening? I ask Jed.

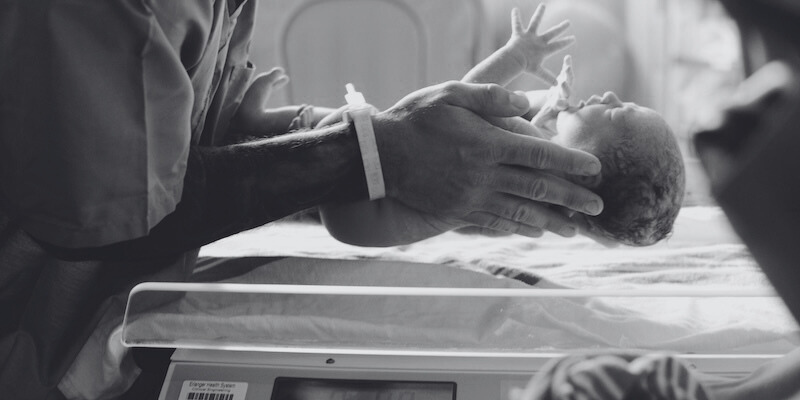

Here is what I know: A baby is born.

The baby is born.

Baby is born.

My baby is born, only Baby is not my baby.

Baby is born, but not completely.

I lie in the bed and Baby is pulled out of me.

I am in the vent when Baby is pulled out of me.

I have nothing to do with Baby’s birth.

I am a prop facilitating birth of Baby.

The baby is a baby of the hospital.

I am not the mother.

I am the mother, but I am not there when Baby is born.

Months from now, over takeout Chinese, I will learn that the word “obstetrics” originates from the Latin obstetricus, which denotes a midwife. This in turn derives from the root obstare, to stand across, as in the position of a midwife vis à vis her patient, and also evokes physical obstacle, something that must be surmounted, gotten around. Confusing because it can’t be the midwife who’s the obstacle, though she stands across. The midwife coaxes the baby out, doesn’t keep it in. Rather it’s the woman’s body—birth canal, hips, uterus’s refusal to contract at appropriate intervals or with enough strength to force open her cervix, elastic gateway from body to world, somehow the cap of the uterus and its own organ—that forms the blockade. The body serves as barrier and pathway, designed to keep its charge inside many months and release it at precisely the right moment, requiring perfect calibration.

The word obstetrics is a trap; the t’s press against each other. Perhaps it would sound better if this mealtime internet search and discussion had happened before the events in question, an unheeded warning or literary foreshadowing. If I had been warned that my body was a trap. It did not. If it had, I’m not sure I would have heard it over the jet-engine roar of What to Expect When You’re Expecting and Babycenter.com advice and the doula’s echoing voice and the ads at BuyBuy Baby.

Early in pregnancy, when, according to my book, the baby was the size of a raspberry or blueberry and I was pale with nausea, I walked through my day buoyed, carrying a secret half divine and half mundane. Already I wasn’t quite myself, though I might have looked it to the rest of the world. Something elemental had fissured, waiting to be spun out. Everyone gets here by way of a woman carrying a secret, yet I felt like the only one to ever experience this splitting of self. Early pregnancy is a state of suspension between the known, rational world, and the spiritual, irrational, even false. Birth, it turns out, too.

But I’m far from prepared for the total severance I’m now experiencing. The forceps have spliced me into body and specter, watching the action from the ceiling above the bed. I knew that, years ago, childbearing meant confronting the possibility of dying during birth, but I didn’t think I’d brush up against that past, not in this state-of-the-art hospital. None of the baby books spoke of what to do if it did. None of the products in the store could help with this kind of time travel.

The thing happening in the delivery room doesn’t exist because I don’t have words to describe it. This isn’t the transition from woman to motherhood I expected. I’m becoming something else, but I don’t know what that is. Without language to label it, I can’t fathom it. I hadn’t foreseen this version of birth—didn’t know it was a thing that could happen. Or I knew it could happen, but only in a world and time far from mine, to people who bear little resemblance—faces aged paint on canvas. The ridges of their grief ironed into something remote and historical and featureless.

I remember the day the fissuring began, or at least the day I became aware of it. I peed and the strip pinkened, one of those life clichés, and afterwards I took a long bike ride with Jed and worried that each bump might dislodge the embryo. No, of course it won’t, Jed said patiently. He reassured me that the kind of splitting I feared wasn’t that easy. That I couldn’t cause it by accident. But he didn’t know.

The fissuring sped with each rapid-fire cell division—the creature, according to my app, morphing from blueberry to raspberry to apple to melon, from embryo to fetus—and now, here, finished with the thing, I’m emptied out and floating in the vent and the fissuring has reached a fever pitch and shows no signs of slowing. I’m splitting faster and faster, breaking down into something I don’t recognize, something older, some other past version of myself, spinning backward, inchoate.

*

Wild West

I keep splitting. The part of me in the bed grips the rails as I spin backwards.

Jackie Kennedy had a miscarriage and then a stillbirth and then a premature baby who died at one day old.

Henry XIII’s third wife, Jane Seymour—following Anne Boleyn and her three miscarriages and subsequent trial and beheading—died days after childbirth. Her child survived and, for a short while, reigned as king. Only Jane, of all of Henry’s wives, endured unblemished in his mind. Death in childbirth cemented her place as martyr.

In the Bible, women often conceive and bear children in a single sentence. Rachel, wife of Jacob, died giving birth to Benjamin. Joseph, her firstborn: cemented as Jacob’s favorite because he resembled his dead mother.

Somewhere a cavewoman without a name gave birth to a son blue and not breathing, buried him in a field.

In a railroad town out west crisscrossed by covered wagons lurching over dirt roads, host to a rat-infested brothel poised above a saloon, I crouch in the squalid outhouse during early labor pains, thinking them indigestion, then realizing no—this is what I’ve been waiting for.

The pains arrive like the faraway ocean waves I yearn for in this arid landscape: cresting into frantic foam, receding until they meld into the dark quiet glittering far beyond the shore, churning, this time with more speed, cresting again. I retch, doubled over, my face just above the hole in the ground swarming with flies.

Months ago, first with child but still flat and quiet in the belly, I doubted my body in the same way, assumed I’d gotten my dates wrong. But as weeks passed, I could ignore the absence no longer. I felt the change in strange parts: A tingling in the tips of my toes and fingers, a churn in my stomach, a slight ache in the small of my back. I was being inhabited.

I waited to tell my family back East until I felt the quickening—first subtle, a pulse of liquid, organs shifting and settling, then sharp juts and turns, the movements unmistakably of some foreign creature, in me but not of me. I share happy tidings, I wrote. I am with child, expecting this summer. The midwife tells me July, should all continue to be well. I have known now for some months but waited for more certainty before writing.

Their replies were spare and cautious. They prayed for health and courage and for the birth of a hearty child. They said they would await news and to send a telegram once it had arrived.

While I hunch in the outhouse, I count the days since the midwife visited. Four, no five days ago I laid atop the bed and she spanned her fingers across the center of my abdomen, yanked up my skirts, clicked her tongue against teeth, schoolmarm’s note of disapproval though I didn’t know what I had done wrong. Babe’s snug in there, but you’re nearing the time. Not much more room left here. I give you three more weeks, she proclaimed, or thereabouts. As the preacher’s wife, she spoke with his same sermon-like elocution, the voice of a self-made prophet foretelling some vague future while also passing moral judgment on each woman under her care. I could tell I wasn’t clean enough or robust enough or modest enough for her liking.

Some women need encouragement. She edged away from the bed, eyes downcast. Was there something she was afraid of, a contaminant that might transfer from me to her if she were to look at me directly?

As I sat up and pulled my skirts back down, she placed a small paper package on the table tied with twine. Raspberry leaves, she said, patting the sack. To brew in case the waters spill and the pains don’t follow. She did not believe in the ability of my body. Some women need encouragement. She edged away from the bed, eyes downcast. Was there something she was afraid of, a contaminant that might transfer from me to her if she were to look at me directly? The door slammed behind her in the strong frontier wind.

Now the outhouse door bangs open and shut in the same wind. It tumbles over the hills and through the valley where scores of settlers have built their homes. My feet sink into the muddy ground, wet soaking through my leather boots and sweat pooling under my arms and behind my knees. A pain hits, radiating from my center. Each wave builds to something stronger than the one before. As the feeling slides down towards my feet all thought flees my mind. I become blankness, a sieve. It releases and I fill back up again, but I have changed in the interval. What returns isn’t quite the same as what left.

I look out of a broken slat and glimpse the outline of my husband through the cabin window. He sits at the fire, something protruding from his lips, perhaps a cigar, his one vice. Everyone needs something, he likes to say, squeezing my thigh. Except you. But he knows I have mine, too.

I cannot allow him to see me in this degraded state, so returning home is no option. Each night I clean the festering green wound on his elbow where, once, a stray bullet ricocheted against the wall of the general store and dislodged the edge of his bone, necessitating an extraction at the doctor’s, weeks of poultices and replacing pus-soaked dressings; but when I bleed each month, I am careful to replace the rags far from his view. If the flow is heavy, I sleep on a bundle of rags by the fire in case blood leaches out. Some of the body—some of nature—is acceptable, some not. This is what must be concealed.

In town, the preacher likes to stand on street corners and speak of Eve’s great sin trapping us here in the world of folly: the tree, the fruit, the serpent, woman’s primal weakness and temptation and fall, the covering of her shameful nakedness, expulsion, and, finally, the pains of labor inflicted upon her that make her feel she might die, and sometimes do indeed smite her. It’s woman’s curse to carry, that birth should hew so closely to death, and from it follows the unspoken rule that babies may be seen cloaked under the mother’s skirts while still inside, and once they are born, but not during the transition between realms. From this, men must be shielded.

Down beside the putrid hole in the ground, I am too tired from the cresting pains to think of where else I might go. With each tightening, my insides barrel down to the base of my pelvis.

I am not sure if I sleep here in the mud or if I am caught in a perpetual state of waiting and tightening, my body led up to the verge of breaking, then retreating from the edge.

Here, in the thick, still heat, shit festers and clogs air.

_______________________________________

Excerpted from Frontier: A Memoir & a Ghost Story by Erica Stern. Available via Barrel House. Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.

Erica Stern

Erica Stern’s work has been published in The Iowa River, Mississippi Review, Denver Quarterly, and elsewhere. She has received support for her writing from the Vermont Studio Center and the Virginia Center for Creative Arts. A New Orleans native, she lives with her family in Evanston, Illinois.