Here are 6 books Tom Waits should read that aren’t Kerouac or Bukowski.

I’ve always been a fan of Tom Waits. But I was a huge fan of Tom Waits in my late teens and early twenties when his whiskey-soaked romanticism, all burnt-out and busted, was soundtrack to my fantasies of life on the down-and-out. And how did I arrive at these fantasies? By reading the likes of Jack Kerouac, Charles Bukowski, William Kennedy, William Burroughs… You know, the kind of books a Tik Tok’er might deem “red flag” reading tastes.

So I am very much not shocked by Tom Waits’s list of all-time favorite books, which features all the usual suspects: Kerouac, Bukowski, Burroughs… In fact, if anything I’m pleasantly surprised by the inclusion of Michael Ondaatje, Breece D’J Pancake, and Frank Stanford, who are three of my favorites now, as a grown up. And while I am not judging him for his tastes in reading—just as I refuse to judge 20-year-old me—I can definitely think of a few non-white-male-barfly writers that Tom might really like.

Lucia Berlin, A Manual for Cleaning Women

That aforementioned “burnt-out and busted, whiskey-soaked romanticism”? Berlin does it better than anyone. But unlike, say, for the perpetually adolescent Serious Mid-Century Male Writer, the stakes are quite a bit higher for a woman trying to navigate the smoke-filled taverns and hangover-hazy motel rooms of the American demimonde—which Berlin does perfectly, finding unlikely poetry in the least sentimental places. Tom, get your hands on A Manual for Cleaning Women, it will change your life.

Fiston Mwanza Mujila, Tram 83

Tom, you want all of life’s sad rich pageant expressed through the sensibilities of assorted drop-outs and hustlers, lowlifes and poets? Have I got the spot for you: Fiston Mwanza Mujila’s Tram 83 (translated by Roland Glasser) takes us to a semi-fictional Congolese frontier town absolutely seething with an atmosphere of insatiable chaos, all of it spilling out of the eponymous nightclub. And don’t worry, Tram 83 has no closing time

Richard Wagamese, Indian Horse

It’s a hard life. But it’s a beautiful life. But yeah, mainly it’s a hard life (which is why it can feel so achingly beautiful). Wagamese’s fictional account of an Indigenous boy’s salvation through hockey, after growing up in one of Canada’s notorious “residence schools” (essentially a catholic boys prison), is brutal and exuberant, offers no cheap pieties, and yet refuses to dismiss the possibility of joy. Like some of your best songs, Tom!

Robert Hayden, “Those Winter Sundays”

Tom, surely you’ve come across Hayden’s nearly perfect poem “Those Winter Sundays”? Here is a poem that maps, with immaculate and earthly precision, so much of the territory you’re seeking in your songs. I’m talking about those unsung, hidden spaces where dignity and tenderness abide without need for the eye of the beholder. I mean, just listen to this:

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

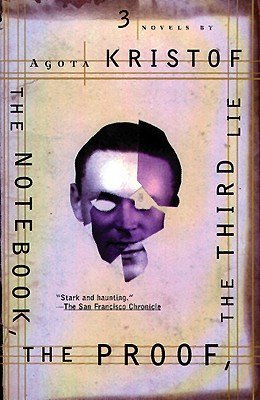

Agota Kristof, The Notebook

You think you have a dark side, Tom, with your Black Rider rock operas and your side-roles as Renfield? Buddy, you gotta read Agota Kristof’s The Notebook (no, not that Notebook). Set in the lawless borderlands of a Europe shattered by WWII, The Notebook follows a pair of twins—children—who exist in their own uniquely amoral universe, unafraid to impose their will on the people around them. It is gripping and harrowing and profound, and it will, by contrast, reveal how very light and superficial all this philandering, barroom heartache really is.

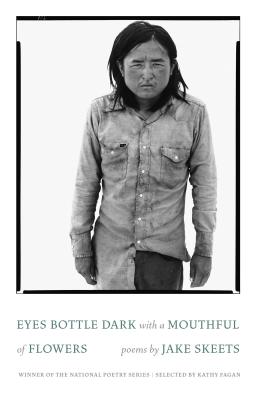

Jake Skeets, Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers

I’ll just quote this stanza from “Drunktown,” from Skeets’s incredible debut poetry collection, Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers.

Men around here only touch when they fuck in a backseat

go for the foul with thirty seconds left

hug their sons after high school graduation

open a keg

stab my uncle forty-seven times behind a liquor store.

I mean, Tom, c’mon man.