One by one the streetlamps come alight. From on my stoop, I watch: the strip of sky between the buildings, the seagulls swirling, the cobblestones below so wet from the past rain they could be rocks along a coast, on top of them a row of beacons burning. Burn, burn, burn. The lamplighter with his long pole turning back the dark. One hundred nights now I have sat here and, Mamme, each time he lights the flames I see your eyes behind the Sabbath candles. Tatte, when he sets his ladder against the cross rest and climbs up, I watch you reach to the display case in your apothecary’s shop. Yankel, my breuder, every time I smell the lamp gas escape I think of you. And start to smile. And want to cry.

How can a son say good-bye forever? How can a brother?

I sit on this stoop and the lamplighter stops to ask what I am writing and I tell him, “A letter.” And he asks to whom. And I say, “My family.”

“All of it?” he says, as if he thinks I mean feters and tantes, zeydes and bubbes, everybody who is of my blood and from whose blood I came.

“Yes,” I say. But I do not tell him I also mean neighbors and friends and everyone I knew in my world up until I left it.

“You’ll be here all night,” he says.

I shrug. He knows I would be anyway.

“They live far away?” he asks.

“A month’s walk,” I say.

If he finds that strange, he does not show it. Maybe he walked as long to get here. Maybe he jumped trains and begged farm wives for rides and hopped the carts of gypsies and was chased by thieves, beaten by thugs. Maybe he kept to back roads, too. Walked at night. Maybe he came from a town not so different from ours. Though I do not think he is a Jew.

“But in Russia?” he says.

I reassure him.

“Well,” he says, “tell them hello from here.” And starts away. Only to turn back. “Tell them,” he calls, lifting his pole in a salute, “I wish for them always a light in the dark!”

Down the rest of the unlit street he does his best to make it true. I watch him till he disappears.

Hello from here. Hello from 214 Talevu Street. It has been ninety-eight days since I sent you my first letter letting you know I had found lodging, a way to make a little money, had not just left on the next boat, would not until I had enough to buy at least one other ticket, that I would wait to hear from you, or till one of you—sometimes I dreamed it could be all three—might arrive at Stepashin’s Photographic Studio and Supply, peer in past the cameras on display, their brass lenses and mahogany plate holders and black bellows, and ask for me.

A month ago I sent a second letter. That one I addressed to Tatte’s shop. Sometimes, sitting here, eating my supper of cold herring and old bread, I cannot help but think on what could have kept my words from reaching you. Then I cannot swallow. And when I think what if they did reach you, and still you have not written back, I stand up from the stoop and go inside, or onto the street, anywhere away from where the thought had found me.

Still, I would wait here a year. Another. If I did not now know that to remain even one more day would be too late.

So, a little after dawn I will fold up the blankets Stepashin loaned to me for sleeping. I will put on the hat that you, Mamme, knit for me the night I left and, which, for each night since has been my pillow. Inside Tatte’s valise I will shut all that I have come to own: a change of clothes, a sailor’s sweater, a coachman’s gloves, a frayed bowtie, a pocketknife with a broken blade, three pencils, and whatever paper I have left after I have finished writing this. Then I will leave the shop. I will lock the door, slide the key beneath it. I will walk down to the docks wearing the too-large clothes I took from Tatte, Yankel’s too-small shoes I used to replace my soldier’s boots, the short coat with the pocket Mamme stitched into the inside in which I’ll slip my steerage ticket along with the papers to prove to anyone who asks—port police, inspectors from the Baltic-Atlantic Line, whoever Stepashin will have alerted—that I am not an army deserter, not your eldest son, your older brother, not someone who had left his family to face the consequence of what he’d done, not me.

My name is Yankel. So many times have I said it to myself. Trying to breathe beneath the hay of the cart in which I fled—Your name is Yankel—walking a moonlit road through unmown fields—Your name is Yankel—wandering these winding streets besides the banks of the Daugarva—Your name—over and over, with each step, each puff of dust—is Yankel. And still, inside my ears, my mind hears Shimel, my name for all my years till now. Shimel, my mind tells me, your name is Yankel. But behind my eyes, what can this name show me but you? My breuder’s eyes, my breuder’s face.

Yankel, if you knew how I study you! Like we were boys again, holding candles, standing shirtless before our reflections in the windows at night. We’d lean close, inspecting our upper lips for hints of fuzz, wondering would we be able to grow a wonze thick as our father’s, would it be, on both our faces, the same brownish red? How you tried to match my muscles! How you mimicked the poses that I made! How, when you would fail to magically be bigger than your big brother, you would do what you always did to make me laugh. A little wiggle in your ears. Then your nose. Then your whole face while you tried to stop from laughing, too.

Little breuder, you should be here with me! We would walk streets lined with houses painted all the colors of Tatte’s powders, drink kvas on the docks beneath the hulls of steamships so huge they could fit inside them even your farts. There are whole trolley cars pulled by teams of horses, a constant crush of droshkies clattering back and forth from stores to bars to cafés to theaters. In summer, when I got here, the city bustled even after midnight. I have seen gentlemen placing bets on hedgehog races, ladies pedaling tricycles along the street. In the square before the National Theater I watched a demonstration of Yablochkov’s candles and I have seen their bulbs that burn without a flame, squinted up at their electric light. And shut my eyes. And seen your face. And stood there, in that awestruck crowd, keeping my eyes closed as long as I could. If you could see it through your brother’s eyes, you would understand. If I could tell it to our mother, she would show you.

Mamme, do you remember the way that we would draw? When I was seven, eight. You would try to teach me to take what my eyes saw, make my hand re-create it on a page. I would try. And fail. And fall into such fits, squeezing my fingers to nearly breaking, beating my fists against my forehead, until at last you uncovered where my talent lay. Go find a picture, you would say. And I would rush around searching for something I thought you’d like. Mittens stuck on fence slats to dry. A birch fallen across the brook. Which, then, I would sit and memorize. Every line, shape, shadow. Until I could bring it in my memory back to my mamme. I would sit on your lap, holding the pad, and you would reach around me with your pencil, bent so I could feel your heart against my back, your cheek against my own, while I described what I had seen in such detail that as if your fingers contained the same anointment as Elisha’s bones, you would bring it back to life on our page. Perfect as if drawn from your own sight.

Why did we never try a face? I do them now. Not through drawing, but with words: descriptions of strangers’ faces scribbled down so that a loved one, somewhere far away, might unfold a page and, with the aid of what I’d written, draw themselves a picture in their own mind.

Each day, I sit on my valise outside Stepashin’s studio, waiting for the leavers to pass by. Sailors with sweethearts, soldiers shipping out, friends sentimental from a night of drinking, mothers and fathers spending last hours with a daughter or a son. People who stop at the shop’s portrait display, cup their hands around their faces, peer inside: the painted backdrop, the velvet drapes, the chairs where someone else, someone with money, might sit before Stepashin’s lens. Sometimes I’ll see the magnesium flash caught in the face pressed to the glass. I’ll wait until the yearner steps away. Then—“Excuse me, friend”—offer him a chance to take his loved one with him for a few coins.

On the cobblestones before me I place a crate, drape it with my jacket, invite the subject to sit. For a minute or two I simply watch them. Then I begin to write. Not only what I see—bend of a nose, shape of an eye—but what I watch happen before me: the way a lady’s nostril flares at something her lover says, a child’s eyes brighten at the approach of a horse and dray. Once a sailor leaned forward to whisper he’d prefer that I not mention his bad breath. But I did. Because I glimpsed his sister roll her eyes at the request, a fond exasperation I wanted her to feel again when, in a month or two, she might wish to remember. Another time, I watched an old man comb with careful fingers a part onto his completely hairless head. Saw his wife fight an urge to, with her own fingers, adjust the styling. So I adjusted: the hair that was still there only in the memory they shared became a way that she, over their years, would touch him. Each letter picture I pushed like this. Just a little bit. And for this they paid ten kopeks each. For this they came all day.

At the end of that first one, Stepashin stepped out of his shop, locked up, walked straight to me. Would I, he asked, do one of him?

“For who?” I asked.

“For you,” he said. “So you can remember me tomorrow.” Reaching over, he put ten kopeks in my pocket. “When you will be gone from before my store.”

But while he sat there in his trim beard and beaver hat, fierce eyes blinking out from the black frame of facial hair and pelt, I wrote, instead, a contract: to him I would pay a ruble each week, only to use the street outside his studio. To me, he would give a place to sleep, inside, just behind the front door. Where anyone trying to break in would have to wake me. I watched him take in, the way men have all of my life, my unimpressive height. “I was a soldier,” I told him.

“Was?” he said. And I watched him calculate the age in my still-boyish face. I should have seen it then. But, at the time, he only asked my name.

At least I knew enough not to say Yankel, not to say Shimel. Instead, I told him Shura. A nickname that I knew would not mark me as a Jew.

Aleksander Aleksandrevitch Aleksandrei: the full formal version that, in a moment of panicked inspiration, I gave him, and that, from that day on, he always used.

“Aleksander Aleksandrevitch,” he would say, “you may keep your things inside the storage closet.”

“Aleksander Aleksandrevitch, please do not bring your supper in; I cannot have the studio stinking of fish.”

“Aleksander Aleksandrevitch”—even after I had been opening the door for him, greeting him good morning every day for months—“if you must light the lamp before retiring to the floor, please take care, upon your waking, to leave the chimney clean.”

His father had been an officer in the last tsar’s army, an inventor of military machines, and Yefin Eduardovitch Stepashin paid close attention to any manner of device, though none more than his cameras. To me, he hardly ever turned an eye, rarely seemed to notice I was there. Which is, surely, why—despite sometimes a slipup of mumbled Yiddish, despite this snitch of a nose here on my face—it was an arrangement that, for a while, worked. Only during downpours, when he would rap on the window, beckon to me, would what was between us seem something more.

While I shook out my hat, stood trying not to drip a puddle, he would speak of things I still struggle to understand. Sometimes, I was not even sure he was talking to me. Fingers fluttering among his cameras, he’d reattach a tiny rubber band, mumbling about a “rebound shutter”, “aperture”, “exposure”, as if explaining concepts to the device itself. Sliding a wood frame into a slot, he spoke of “bromides”, “emulsion”, as if to the sheet of glass it held. But for all the unfamiliar words he used, I began to see that he was talking, always, about only one thing: light. Not what his contraptions might do with it, but what it is.

The luminiferous aether. This Stepashin calls it. Light, he says, travels from a source—the gas flame in this lamp above me, the sun that will tomorrow brighten the sky—and hits whatever stands in its path—this page, this pencil, my face—and bounces off of it in waves. Waves that ripple through the aether waiting in the air. And, moving it, make it something we can see. The way water in a glass is clear till stirred. This is what enters our eyes. These luminiferous waves, this aether that is stirred in such a pattern that the things off which the light has bounced appear. Without the waves, the aether is invisible. Which is what we call dark. But even in the darkest blackness, the aether is still there. Waiting to be stirred. So we might see.

I wish my mind was better made for this. I wish, Tatte, you were here to sharpen it. You would ask me your questions, the raised eyebrows and downward-dipping mouth that Yankel and I always feared. Because we knew that what was coming would make us question what we had till then assumed was true. Sometimes, I try to do it for myself—I have attempted to see your silence from some angle I have not yet considered—but it is not the same. You cannot say, the way you always would when we were stymied: “Let’s see if we can’t think up an experiment.” And, with your powders and potions, you would find a way to test even Stepashin’s aether. When I was a kinde, I could watch for hours while you worked. Melting, measuring, filling bottles with mixtures for sick strangers, neighbors. Even, sometimes, for your son. Meyn zun, you would say, and invite me over to smell an unknown scent, ignite shavings into a crackling of colors, watch as you mixed into some oil a powder to make it glow. Phosphorus, you said, that day before I left. And sealed the tiny vial, the glass flasch that I wear still on the chain you placed around my neck.

Sometimes, listening to Stepashin speak of waves and light I place a hand over my chest and feel it—the flasch—and, watching him work, am struck by a sudden sense of peace. An inexplicable closeness. Which is the only reason I can give for my mistake.

It had been raining. He had been talking. I had been thinking—if only the waves of light could pass through solid things, travel in an uninterrupted line from ricochet to our eyes, you could see me from five hundred miles away, I could see you—when he turned to me and asked, “Aleksander Aleksandrevitch, do you know anyone by the name of Yushrov?”

So strange, after all these months, to hear our name. From him. Still the answer should have been simple had my mouth not refused to make it, had it not, instead, as if needing to feel the word, said the name back: “Yushrov?”

“A Hebrew name,” he said. He had finished closing up, we were stopped just inside the door, barely a foot apart, my hand on the knob, ready to open it for him, his on the handle of an umbrella still in the stand.

I managed to make my head shake no. Though out of my mouth there came, unbidden, “Why?”

Outside, the rain drummed at the door, ran down the windows, made the shadows on that side of his face appear to move. “I received,” he started, “a letter—”

“From …?” I watched him wonder: hadn’t he just told me? Or did I think the name had been who it was addressed to?

“Yankel,” he said.

I tried to make my face a picture about which, had I been peering at it, I could not have found anything to write.

“Shimel,” he said.

And I could see on his face that I was failing.

“Do either of these names—”

“Two?” I said. “You received two? To each?” He released the umbrella handle. I released the knob. My hand was shaking. “Show them to me,” I pleaded. “Fima”—it was the only time I ever used the familiar form of his first name—“will you?”

“That depends,” he said, “on who I’m showing them to.”

And so I told him, watching his eyes narrow, as if he was trying to bring something out of focus into sharpness, until, by the time that I was done, his lids had shut almost entirely, and I knew thatI had been wrong to.

“So,” he said, “you are a deserter.”

I should have caught the strange lack of surprise, as if I’d simply confirmed something he’d heard, but I was too intent on trying to paint for him a picture of why: the death sentence that is conscription for a Jew, the friends I’d seen succumb to officers’ demands, suicide posts, unsurvivable conditions, the impossibility of staying alive for the mandated twenty-five years.

To which he said, “You are a Jew.”

“I am,” I told him, “the same man who, for a quarter of a year, has greeted you each morning, who guards your shop at night.”

He lifted the umbrella out of the stand. “Who did.”

From under his other reaching hand, I grabbed the knob, held the door. “At least,” I begged, “give me the letters.”

He set his fingers on top of mine. Such an unexpected touch: my hand, without his on it, would have slipped off the brass. “The only letter I received,” he said, “was from the military police. Telling me they had come across another from your family. Addressed to here.” Where, he said, his voice soft as his artists’ fingers felt, he would, out of respect for the time we had spent in each other’s company, allow me to remain till morning, till the usual hour that he would open the store, when he would return with the police.

Already, it is almost tomorrow. Long ago, the last droshkies passed by Talevu Street, left the avenue that is just visible at its far end empty of all but the gas lamps’ glow, gone still but for the shifting of the few remaining leaves.

I know that I should try to sleep. But I cannot stop thinking about the police. Not the ones Stepashin will bring. But the ones who already must have come to you. Mamme, did they wake you at night, break in, destroy your drawings looking for letters from me? Or by then were you already gone? From our house? Tatte’s pharmacy? Yankel, did they demand your papers? Did you tell them I had taken from you your very name? That I had stripped from my own brother his only proof of himself?

No, there will be no sleep for me tonight. This last night beneath the sky we still share. Where I am going, your night will be my day, my day your night. And with each passing one I will become less your brother, less your son. Until I am someone so far from you in a life so different from this that these words will be the last not just to you, but from me. Mamme, you will say I will always be your son. Tatte, you will tell me it is only an ocean, another country, a few more miles. But I have already traveled more than a few from you. And I know that this is different. By this time tomorrow I will be far out on the sea, deep in a shaking hull, surrounded by the sounds of sleeping others, mouthing into the steerage dark a single syllable—‘new’—trying to get it right—‘new’—the first sound of the name of the place in which I will never again be called meyn breuder or meyn zun.

Outside, the street seems to have already begun to disappear. There are only burning lamps, cobblestones fading away beneath their glow, gaps of blackness between. And my lantern in this window. Lighting me. I will let it burn all night. I will let the chimney blacken. I will wander among the cameras on their stands, touching all the knobs, turning the rings, making their rubber bellows creak. I will set a match to the magnesium, watch the flash explode. And in the darker darkness after, the acrid scent of smoke, I will push open the velvet curtains, step into the backdrop, sit on the chair, stare into the lens.

Well, in fact, other than keeping the flame lit, I have passed these last hours tossing in my blankets, trying to imagine what I could write here at the end. Now, the blankets are folded. My valise is packed. Outside, the night is growing thin. And through the shop windows I can see it: the first faint waves of daylight reaching down into the street, ricocheting off wheel spokes, shutter slats, showing a flutter of wings, first slight stirrings in the aether. I like to think of it, there all night, waiting for a ripple of light to come and give the things of the world shape, abiding, always, everywhere. Even when there is no one to see it.

For the past hour, watching the window light lift out of the lantern’s flicker all the devices that fill this room, I have been thinking about this century’s beginning. How back then no one had so much as conceived a camera. How a mere fifty years ago the journey I am about to make would have taken twice as many days. How barely fifteen years before today not one soul had ever seen an electric light. And fifteen years from now? In the new century? Maybe by then we will have cut the ocean crossing in half again. Maybe we will have found a way to send light around the earth, and I will once again be able to see your face. And you mine. But until then, all the time that we are hidden from each other, I will know that you are there, in the dark, as there as the spokes, the shutter, the street outside—its cobblestones, abandoned carts, the tops of hitching posts painted white by perching gulls—that, lost to me all night, has returned.

And here he comes again: the lamplighter, crossing from one side of the street to the other, unlatching the panes, reaching up, snuffing the flames. Watching him it seems as if he might have just kept walking. Followed the night around the globe, lighting lanterns until the dark crossed into day and, coming upon the flames already lit, he flipped his pole to its snuffing end, simply kept on. Maybe, some night in another city in another country I will see him coming down another street. I will call him over. I will ask him to bring a message back to you. “Tell them,” I will say, “hello from here.”

He nears. A nod. I nod back. Reaching his pole to the lamp above me, he says, “They’ll be up all night reading it, too,” and I wish I had another hundred pages. I wish I had something more than this to send. If I had learned to use the contraptions that all these nights have kept me company, paid more attention to practical things Stepashin said—how to load the plates, train a lens on where I’d sit, focus it on myself, somehow trigger the shutter—if I knew the way to free the captured light and imprint it on a piece of paper, I would do it for you. But all I know to do is this:

His skin is puffy from lack of sleep. His hair sticks out from beneath the hat his mother knit, wild, unwashed. The same color as his brother’s. But his mustache has grown in a little darker, a little more full. Almost, now, as thick as his tatte’s. His tatte whose beard he used to like to squeeze in his small child’s fists, just to see his fingers disappear. He wishes now he had such a beard to hide his own face. The puffiness of his lower lip, raw from biting it. The shaking of his upper, delicate—always, he thought, too like a girl’s, too like his mother’s—its shape as deeply pinched as the pie crusts that she makes. He can feel her fingers on his mouth. Pressing it. He shuts his eyes. With them closed he can see yours better. If he could he would stay like that forever, remembering his father’s, his brother’s, his mother’s. But when he opens his eyes again, there is just him, sitting by a still-burning lamp, watching, in the window glass, his own reflection. Your oldest son, your only sibling, your once was Shimel saying good-bye. Good-bye, Yankel. Good-bye, Tatte. Good-bye, Mamme. I wish for you a light in the dark.

__________________________________

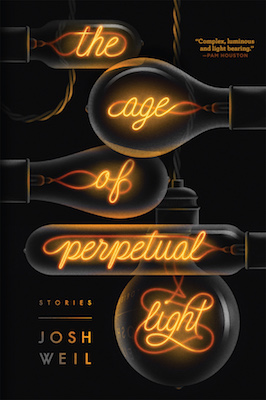

“Hello From Here” is excerpted from THE AGE OF PERPETUAL LIGHT © 2017 by Josh Weil. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.