My wife was, at one time, a very beautiful woman. But over time, her beauty faded, and with it went her desire for me. There were so many years of notoriety that had held us together, my success, her adoration, my appreciation, the agreements we had made.

It likely wasn’t fair of me to see her beauty as fading, it would have been fairer to see it as maturing, and yet if I’m being honest it really did look to me as though it were withering not ripening.

At first the changes in my position were devastating, even though they were largely ideological. It wasn’t violent, but quiet. My wife and I would weep gently in each other’s arms.

And yet with time, the lower I felt, the brighter she became, though to me that brightness felt punishing, like exiting a theater at midday.

I had lost everything. And at the beginning, she felt she had lost everything too. It was a shared loss that at first brought us closer together. There wasn’t a way for us to remain viable without my career, we told ourselves. It was what provided us an excuse to remain in tandem. The university was our container, it was where we had met, it was where we had formed.

But I had died.

That is, I became dead. To the world, and to me. And yet she was alive, my wife said.

Her dog enjoyed my spot on the bed.

She would caress it while I lay far out, pushed to the edge. Such gazing, such devotion. She would invite it on the blanket and rub its long, blond ear.

*

Early in my career I taught a nature writing class to a small number of students, each of whom was meant to research a plant that interested them.

Every meeting we would discuss a different student’s work by performing a collective interrogation, all of us asking one student questions rapidly in succession about their plant and their pasts as a way to access something deeper. The student in question would become flustered and exposed, providing an opening for their subconscious to emerge. These questions and answers, paired with a botanical inquiry into the plant they had chosen, culminated in a lyrical theory of each student’s driving inquiry, which was eventually revealed. This aided them in their writing—it gave them a root.

*

One of my students was beautiful.

*

Although I didn’t look at my students through the lens of desire, it was impossible not to notice her beauty, and I did so objectively.

*

She chose for her plant, Gomphrena, a tender annual with lovely, papery, globelike heads. Called the Amaranth of poets, this flower was considered the emblem of immortality, and was said to have been worn by the Thessalians at the funeral of Achilles. If cut before fully ripe, tied in bunches and hung upside down to dry in the airy dark, Gomphrena would retain its color for the entirety of the season, lasting seemingly forever in a dried bouquet.

The young woman said it was the power of influence she wanted to explore. She wanted to investigate who had it, and how it worked. How did power propagate.

This was the start of many long conversations, and our classes often went over, but no one complained. We read both horticultural and literary texts and discussed them at length, writing reflections and responding to each other’s ideas, and at the end of the term, we presented our finished work. I didn’t present myself, but I still say “we.” It was an experiment in collaboration, in alchemizing ideas out of plants. It was meant to show how the history of human evolution arises from our literary relationship to the earth. The class was called “True Nature.”

*

My beautiful student was last to present her work.

She said to think of a truth in nature is absurd. The birds, the flowers, the trees, the soil—each of these entities had a history that preceded its current state, and each stage of that history was informed by both regeneration and violence, and political and environmental factors that impacted it directly and indirectly. If there was any truth to be discovered, it was that nature itself was not neutral, and any so-called purity was imposed upon it by those of us with the need to use nature as a shield from our own complicity with systems of destruction.

It was impossible to simply “be” in nature, she said, without complicating the notion of “nature” itself, just as a border has nothing to do with the land’s actual requirements for entry or exit. In fact, she said, it wasn’t nature at all that man was searching for in his desire to exist closely within it, but a projection of the desire to be without politics, which man misinterpreted as being without consciousness. Man envied this seeming consciousnessless of nature, for he knew, deep down, that ego alone would never solve the problems of the heart.

But nature did have a conscience, she said, or it could have one, or two, or twelve. It was that man had no way of knowing what form that consciousness took, or how to interpret it, let alone how to contain it or embody it, and he never would, unless he gave up all control forever, and not just the illusions of it.

She wrote this in the form of a play and performed all the parts herself as a surprise for me. Her idea was expressed through a reenactment of the funeral of Achilles from the perspective of the flowers growing near his funeral pyre.

It was exquisite. And I was jealous.

I began to doubt whether her work was wholly original. There was something about her conceptual framework that felt familiar, established, as though it were something I myself had studied. Of course, one could argue one’s way in and out of anything, one could evoke feelings of ancient ideas and still be contemporary, and anyway, that was why we were here, it was the whole point of literature, to question, to interpret, and to reimagine.

I resisted the thought because I knew it was ungenerous, and yet it kept coming back in. I recalled her admissions essay to the course, which had been very good, but still, the sensation of wrongdoing ate at me. It just didn’t seem possible.

I questioned her. You know, in the spirit of discourse. It was the wrong thing to do.

She became a professor.

*

I’ve always been drawn to the written word. It began early on with comic books, and I read the same issues over and over. I never tired of battles between good and evil, stories of death and memory, all the darkness and all the light that felt so elusive to me then, so out of reach. I recall my mother relenting to my plea to please, let me read at the dinner table.

The more time passed, the more books I had to get through, and I began to read as if in a race against time. Simple pleasure in reading, the childhood delight of hunkering down with a good book and a warm bagel on my chest, sitting sideways on a sunken armchair with my head on its arm, no longer felt possible. Reading became an intellectual pursuit, one of focus instead of escape.

But maybe, with age, imagined realities that had felt out of reach and otherworldly began to feel more real, and this realness was what stripped the luxury out of the act of reading. The more I knew, the less I was moved by the fantastical stories I had reveled in as a child. Fables and allegories had once worked their magic on me, but now that I was myself capable of seeing how the tricks were done, and even able to play those tricks myself, I was bored. Now, when I read, nothing new occurred to me. Perhaps I had moved away from reading entirely, but the idea was frightening.

Was this what some people called analytic contentment?

I did not feel content. I wrote and read to get back to the ravenousness of childhood, to those days of dogeared comics stained with cream cheese at the corners.

But I also did it to prove that my mind was growing into something more than a child’s.

*

I didn’t think I had come to the end of my utility. I looked down on my younger colleagues with their notions of what education could accomplish. They wanted too much. They wanted to reinvent everyone’s methods. They wanted to do away with the systems that they felt imprisoned them, and yet in a way, they enjoyed their imprisonment because it gave them something to abhor. I found them lazy. They hated working. They just argued and argued. I asked them to take walks with me through peaceful places in the city, and they refused. Why would we walk? they asked, when we could talk right here?

What did they want from me? To cease to exist?

There’s such a thing as empathy, I told my colleagues. Don’t forget to be kind, I said. Don’t forget about joy! Whatever happened to having fun.

I had always been one of the outsiders, or so it had felt. I had led the way, written a map of alternative paths. And now they were asking me to kindly get out of the way. I guess I should have just done that, moved aside. But it’s not so easy.

On the other side of my career was a threatening darkness. The darkness not of mystery but of fear.

Perhaps, I told myself, there was a way I could see it as a risky adventure in self. After years of being face down in water, maybe now I had an opportunity to flip over, maybe I could publish new work—it had been so long—to correct the misinterpretations. I could rebut the critique of my beloved department, the diminishment of my value, by providing the public with a work that challenged my colleagues’ precious positionality, the ethics of relying on identity for the cultivation of merit, work that was about nature in its totality. Something rooted in the land. I’d set out into the wilderness and write about my experiences training falcons, eating nothing but seeds and mushrooms. Now, finally, I had time. It would be a work of genius—as my writings had been referred to once before, but not lately. A word I liked to say demanded definition, yet how can one define magic? I was attached to it, that word. But I only used it with a sense of embarrassment.

There are books that move people just by being read, my colleagues said. Books that are for people. Then there are books that can only move people who come to those books with prior knowledge, who have read the other books to which this new book alludes. Such books, among which my colleagues included my own, could only be considered complete when they were reflected upon by scholars: the people responsible for writing and then reading the books to which books like my own made reference. These reflections, too, would then be couched in a language too confusing for most readers to understand. You had to be willing to work hard to learn it. You couldn’t just read, you had to have read. To learn, you had to already know.

To my young colleagues, the best kinds of books—the ones that could move people just by being read—were like picnickers on the side of highways. There they were, sitting comfortably on the grass with a sandwich, wiping their hands on their pants, visited by deer and by sunlight.

Whereas my books were like clouds, up high, with matter but no mass.

I can appreciate the need for books that entertain, but I ask: Can you imagine contemplating a groundbreaking idea while eating a sandwich?

I do like sandwiches, of course.

__________________________________

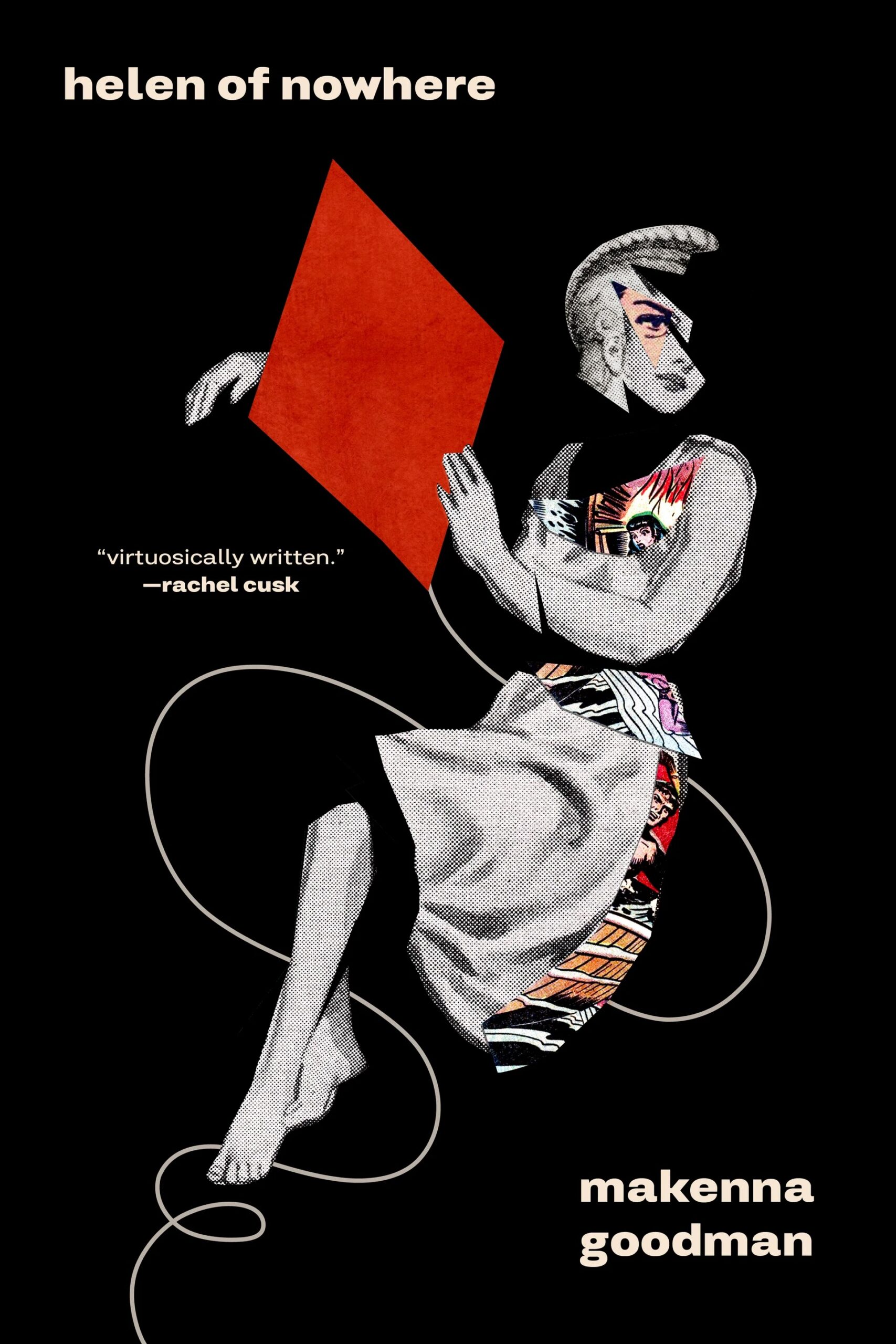

From Helen of Nowhere by Makenna Goodman. Used with permission of the publisher, Coffee House Press. Copyright © 2025 by Makenna Goodman.