Helen Frankenthaler: From High Society to Downtown Art Scene in 1950s NYC

Alexander Nemerov on the Life and Times an American Painter

Helen Frankenthaler walked into the lobby of the Hotel Astor dressed as Picasso’s Girl Before a Mirror. Her costume was outlandish, like a Technicolor cartoon: a dyed mop on her head for yellow hair, pajamas for the feeling of the boudoir, a painted curtain wrap for a backdrop, a mirror in her left hand. Two nippled balloons floated on her arm and hip, displaced breasts set at crazy angles. By her side was Gaby Rodgers, her friend and roommate, impersonating a cover girl: sporting a blouse of black-and-white diamonds, as retiring as a racing flag, a red-dyed mop on her head, and the current issue of Flair, a new fashion magazine. The two young women, both fresh out of college, walked through the lobby to the elevator and took it to the ninth floor.

The door opened to reveal a vast ballroom, the largest in America. A din of alcohol-fueled conversation rose to the rafters. More than a thousand partygoers were celebrating Spring Fantasia, an artists’ benefit costume ball. Large cut-out mobiles hung from the ceiling, depicting schools of fish, a sunflower, a vast bird on a branch, a bodybuilder, the moon. A couple of revelers wore Vesalian anatomical suits showing nerves, blood vessels, and striated muscles. A man walked around dressed as a spider, complete with a 15-foot web and large fly. A trio wearing black and white called themselves “the Death of Color.” A husband and wife, the makers of Christmas card art, dressed as Parisian pimp-and-prostitute “Apache Dancers.” One reveler sported only a fig leaf, and another, calling himself “the Rain Maker,” wore long strings of buttons that clacked together as he danced.

Helen and Rodgers joined the exultation, at home among the partiers, having fun. But they were also on a mission, keen to create names for themselves. Rodgers was intent on becoming a serious actress; Helen had her own plans. The ball was a benefit for the Artists Equity Association, an organization devoted to establishing rights for all artists. Its president, 60-year-old painter Yasuo Kuniyoshi, in attendance that night, worked hard to achieve this noble goal. But Helen and her friend did not have their minds on equity. What if there were good artists and bad artists and, yes, great artists? What if it all was not fair and what if fairness was for losers? Then there was no equity, only a hierarchy based on ambition and talent and luck. A few people succeeded. Most failed.

The same with celebrity. The ceremonial emcee that night was Gypsy Rose Lee, 39, the famous stripper and author, who at that stage of her career had been performing striptease shows for a touring carnival—earning a vast income—and hosting two shows on the intriguing new medium of television. No doubt it was a thrill to catch a glimpse of her. With her sparkling gown and crazed tiara—a swirl of hanging stars protruding from her head like a rack of celestial antlers—she cut a figure at the ball. Rodgers’s rose-filled cover of Flair—a magazine that Lee had written for—maybe caught the star’s attention.

Becoming an artist was not necessarily in line with the family mythology.

But Helen and Rodgers aimed to be well-known themselves, unfazed by the older artists and entertainers who had seen so much more of the world than they. When Life magazine ran a feature on the Astor ball some three weeks later, the two unknown young women merited the only color photograph. Their outfits and personae drew attention, muscling some of the more earnest but less flashy costumes out of the limelight. It was a way of becoming public, of filling the stage—a contrast to how insecure they both really were. Two photographs taken at their lower Manhattan apartment a few hours earlier show them looking sweet and sedate, like adolescent girls before a night of trick or treating, with Helen standing above her friend, who sits in a butterfly chair.

At the ball, however, the two young women grew larger than life, knowing well enough how to be a party’s center of attention. The Life photographer pictures them from below, giving each a special stature. Magically, they assume the publication’s house-style sexuality: pretty, white, wholesome, dishy, maybe available. Helen looks long and coltish. The irony of Rodgers holding a copy of a national magazine as she appears in a photograph for another national magazine turns out to be no irony at all. The cover girl and her cover girl friend knew how to draw interest.

Who cared if they had barely accomplished a thing by that night in May 1950?

*

Returning to Manhattan—after her college years studying art at Bennington—Helen faced a serious challenge. Her mother was a formidable woman. Elegant yet earthy, Martha Frankenthaler was a person of vibrant enthusiasms and impetuous moods. Recalling the sisters’ childhood, Marjorie remembered the “childish expectancy” of their mother’s face when she was excited about anything, “the party edge” that was “always there in her talk and in her eyes,” the way their father would treat his wife “alternately as an adored goddess and a spirited child.” Back then, it had been “wearing on a day-to-day basis to live with her high energy and excitement,” and when Helen returned to Manhattan after her Bennington graduation, her mother’s capriciousness was there as always. But so was a tough and imperious conventionality. Impractical herself, Martha exerted many practical demands on her daughters, and she doubted Helen’s intention to become a painter. To this venerable woman of the German Jewish haute bourgeoisie, Helen’s career choice was as mystifying as her aim to move to the West Side of Manhattan, a virtual foreign territory to a family ensconced on Park Avenue and environs.

A photograph taken two years earlier, in July 1948, back before Helen’s senior year at Bennington, shows Martha’s power in those days. Then 53 years old, she stands imposingly next to her 19-year-old daughter. The occasion is Helen’s departure with Gaby Rodgers on an ocean liner for Europe, a trip the friends took that summer. Martha has come to the girls’ room to bid them farewell, and the cake Helen holds says “Bon Voyage Helen.” The confection marks Helen’s nascent independence—she is about to travel farther from her mother than ever before—but Martha’s plump glamour crowds the room. Helen appears to hold the cake slightly to one side, as if worried that her mother might smear the frosting. The word “upstage” is not too strong to describe the presence of the Frankenthaler matriarch—whose March birthday, coming just before the annual St. Patrick’s Day Parade, always made it appear to Helen when she was a child that the pageant took place in her mother’s honor: a fantasy that Martha, vain and impetuous and imaginative, did not dispel.

Now in winter 1949-50, only slightly more than a year after the bon voyage photograph, Helen had come back from Bennington and directly into her mother’s orbit. Martha’s expectations likely had to do with the family name, the ongoing prestige of Judge Frankenthaler throughout Manhattan. The time when she and her husband had introduced their three young daughters to Sara Delano Roosevelt, the mother of the president of the United States, as she stood at the door of her Upper East Side brownstone—this was back in 1938—still represented the Frankenthaler family’s social connections and aspirations. Becoming an artist was not necessarily in line with the family mythology.

Martha wanted Helen to be like her sisters. A photograph taken in 1949 or 1950 by Jerry Cooke, an Upper East Side society photographer, shows Helen with Gloria and Marjorie. All three black-haired sisters wear black sweaters, and a gleam shines alike on their faces, highlighting both their individual uniqueness and their sisterly unity. Marjorie and Gloria were already married, Marjorie to Joseph Iseman in June 1947 and Gloria to Arthur Ross in January 1946. Both had immediately started families: the Isemans’ first child, Peter, was born in 1948, and the Rosses’ first, Alfred, in December 1946. The photograph, which perhaps Martha commissioned, implied that Helen might follow in their path—meet a man, have children; be herself, of course, but be also indistinguishable from her siblings.

Having none of this, intent on demonstrating that being an artist was a legitimate and not frivolous occupation, Helen enrolled in graduate courses in art history at Columbia University, aiming for an academic legitimacy that would impress her mother by showing that art had intellectual prestige. It was fall 1949, and there she sat in a packed and darkened auditorium, staring at the lantern slides projected on the screen as she listened to the quiet, almost whispered eloquence of the teacher, Meyer Schapiro, one of the world’s most erudite art historians. “The beam of the projector was a search light on the world,” recalled one of the master’s students, the writer Anatole Broyard. “The students shifted in their seats and moaned” as Schapiro “danced to the screen and flung up his arm in a Romanesque gesture.”

But Helen was unimpressed. She realized that justifying her choice to become a painter by taking courses in art history was beside the point. Either she was an artist or not. She did not need credentials and she did not need to prove herself to anyone besides herself. She had learned enough for a lifetime at Bennington; she had no need to “learn anymore except in my own terms.” With her family money, she had the financial independence to take the next step in confidence. She stopped taking courses at Columbia and moved out of the family home into an apartment on West Twenty-fourth Street with Rodgers. The transition was not always smooth. The creak of the Eleventh Avenue freight train every night at 1:10 am was an unaccustomed sound to the Upper East Side girl. But it was thrilling to be independent. Helen began to spend more time at the tiny fourth-floor studio she and Sonya Rudikoff had rented on East 21st Street.

Helen was unusual among young artists in lower Manhattan, few of whom had much cash. The painter Grace Hartigan, whom Helen met later that year, lived downtown in 1950 with her boyfriend, the artist Alfred Leslie, in “steady, endless poverty,” Hartigan recalled. A few years later, when she was a little better off, a street vendor selling penny tomatoes and a grim market selling meat at fifteen cents a pound reminded her of the cheap and foul food she and Leslie used to eat in those penurious days, back when Helen met them. They all became good friends, but Hartigan felt her early days showed her “what it means to be poor, really poor,” something that “Helen will never know.”

Helen, it is true, lived a comparatively posh life. She frequented the uptown beauty salon MacLevy’s, where she would have her hair washed and sit under the dryer. She got her hair cut and styled at the tony salon Jean de Chant, or “Jean de Chump,” as she called it when her hairdresser erred. She and Rodgers employed a maid to clean their apartment. Visiting her mother’s place at Fifth Avenue and Seventy-fourth—Martha had moved there after 1946—she would switch on the marvelous new black-and-white television, stepping out onto the balcony (Martha lived on the fourteenth floor) to look around as the mood took her. The disparity between her means and that of her artist friends could be awkward. Helen once thanked Leslie for giving her a ride to New England in his old truck by hastily flinging a handful of coins on the seat as she got out of the car at her destination—an embarrassing gratuity that Leslie found both charming and cheap: a pittance for gas money that reminded him of when Martha Frankenthaler paid him for three days’ work on Helen’s studio with a steak. Helen, like her mother, could be stingy. But she never apologized for her money. She knew she was serious, not a faker or a dilettante, and she expected others to see that seriousness, which they did.

__________________________________

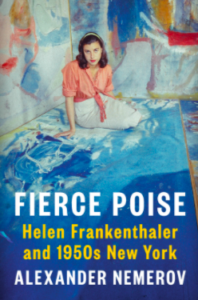

From Fierce Poise by Alexander Nemerov, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (c) 2021 by Alexander Nemerov.

Alexander Nemerov

Alexander Nemerov is the Carl and Marilyn Thoma Provostial Professor in the Arts and Humanities and the Chair of the Department of Art and Art History at Stanford University. In 2019, he received the Lawrence A. Fleischman Award for Scholarly Excellence in the Field of American Art History from the Smithsonian Institution's Archives of American Art. He is the author of several books, including Soulmaker: The Times of Lewis Hine and Summoning Pearl Harbor.