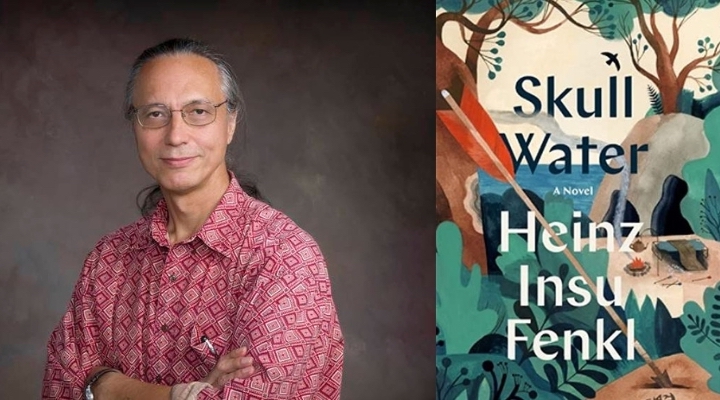

Heinz Insu Fenkl on Exploring Memory, Identity, and Inter-Generational Trauma in Korea

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of Skull Water

Heinz Insu Fenkl was born in South Korea to a Korean mother and a German father who was a GI in the U.S. Army. He grew up in Korea until age twelve, then in Germany and the U.S. His autobiographical first novel, Memories of My Ghost Brother, a 1996 PEN/Hemingway Award finalist, draws upon his childhood, as does this second novel, which is set in part across the North Han River from Sambong-ni, his mother’s native village. “Skull Water was initially a memoir, and I drew extensively from my life experiences in all three places,” he explains.

“All of the action in the novel takes place in Korea, and that is the primary focus, but there are references to details from my time in Germany and also in the U.S. The parts of the novel set during the Korean War years are taken mostly from stories told to me by my Big Uncle and other family members who survived the War.” Skull Water is gritty, mysterious, at times comic, a coming-of-age novel the unveils hidden stories from a time in Korean history that most readers know, if at all, from a narrow perspective. Our East Coast-West Coast email conversation covered multiple continents.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have you managed during our recent unsettled times?

Heinz Insu Fenkl: It’s been difficult and continues to be, but one of the positive things about having to stay at home is that it’s given me more time to write. As I was doing the final edits for Skull Water, the situation with COVID reminded me of how I had lived through mass outbreaks of cholera and typhoid as a child in Korea.

JC: You toggle between 1950 and 1974-75 through most of the novel. What makes these two time periods in Korean history so crucial to your story?

HIF: Those two periods were both marked by dramatic and violent upheavals and rapid transformation. In Skull Water, as I explored the stories of the two generations, poignant and unexpected resonances and parallels emerged.

Memory is double edged because…it’s important to preserve one’s recollections…but the very preservation of those memories is also painful.The early 1970s was a formative time for me growing up, and it was also a volatile time in Korea. Park Chung-hee was “president” of South Korea, but he was more accurately a military dictator—there were severe political crackdowns; the Vietnam War was in its last phases with the fall of Saigon fast approaching; and the country was going through a lot of political turmoil with regular confrontations with North Korea, along with assassination attempts; meanwhile, the economy was gearing up for the “Miracle on the Han,” the rapid development that would come at a terrible cost to workers and the environment. In Skull Water, through Insu’s and Big Uncle’s perspectives, I explore the impact of these changes on their extended families—the disruption of identity and family, the destruction of the countryside, the dissolution of culture and tradition.

The first years of the 1950s, when part of Big Uncle’s story takes place, were a time of even greater upheaval with the Korean War, when the country was devastated and nearly ten million families were separated. My mother’s generation went through that traumatic period, the War having broken out only a few years after Korea’s liberation from Japan in 1945. Those were times they often talked about, especially late at night when they were drinking, and I grew up listening to their stories and trying to understand what they had lived through.

JC: What is the meaning of your title, Skull Water—the precious substance your young narrator Insu, who is fifteen in 1974, hanging out on the outskirts of two U.S. military bases, ASCOM and the former Yongsan Garrison, with his friends Paulie and Miklos, seeks to help heal Big Uncle’s wounded foot? Does it also represent an impossible to find salve to heal the wounds of these moments in history?

HIF: As you suggest in your question, Skull Water could be read figuratively as an impossible-to-find salve. It could also be a metaphor for memory itself. Memory is double edged because, on the one hand, it’s important to preserve one’s recollections (and one of my goals was to document and preserve that time and place in which my novel is set), but the very preservation of those memories is also painful because much of it is associated with trauma and tragedy.

According to a Taoist folk belief, skull water is the fluid that accumulates in the cranium, and can cure any human ailment. In the novel, the main character, Insu (based on my younger self), and his friends set out to dig up a grave to get skull water for Insu’s uncle, who is suffering from a mysterious foot injury that defies medical treatment and never seems to heal. Insu’s uncle is dying as the infection in his foot grows more serious, so there is urgency to the quest, which goes spectacularly wrong and has unexpected consequences.

Skull Water is also about the nature of consciousness and the human capacity for compassion and understanding, especially as it relates to friendship, cultural and family history, and what happens when they are disrupted by colonization and war. The title encapsulates all these issues. At one point, Insu learns about a Buddhist master from ancient times, Wonhyo, who became enlightened after drinking water from a skull. This resonates with the themes of the novel since the title Skull Water also refers quite literally to cerebrospinal fluid, the medium through which processes in the brain occur, the medium of human consciousness and memory.

JC: Which family members most inspired you while working on the book, for characters like Insu; his mother; Kisu’s grandmother, Halmoni, who was a young woman when Korea was still a kingdom, before the Japanese annexation; and Big Uncle?

HIF: In terms of inspiration for this novel, I would have to say it was my Big Uncle (my mother’s oldest brother), since his story is the one that parallels and converges with Insu’s. At the same time, my mother (Mahmi) and my other relatives played an integral part in many of the memories that I drew from in writing Skull Water. I plan to write more about their experiences from the Japanese colonial era and the Korean War years, because there is so much more to tell. As I edited my manuscript, I decided that more of their stories will have to be in another autobiographical novel.

Korea went through such rapid and radical changes in the early 20th century that every new decade must have seemed like a lifetime. Halmoni lived through part of the Joseon period, which ended in 1897 when the Korean king fell into a political trap and declared himself an emperor. By 1905 Korea was a protectorate of Japan, and then it was annexed by the Japanese Empire in 1910 until the end of World War II, when Japan surrendered to the United States. Then it was only five years until the Korean War broke out in 1950.

In telling Halmoni’s story, I realized that one of the books I want to write in the future is Three Widows, about my mother and her two older sisters, following their stories from their childhood under Japanese rule, to their survival through the Korean War, to their immigration to the U.S. My mother would tell harrowing stories about the war years, including how she disguised herself as a boy and followed the troops during their retreat to the Pusan Perimeter.

JC: Three Widows sounds intriguing. In Skull Water, your primary narrators, Insu and his Big Uncle, are bonded by family ties; do they also have a spiritual connection?

In difficult times—like war, or life under a military dictatorship—human nature tends to be amplified.HIF:I hope readers will come away with the sense that Insu and Big Uncle do share a strong spiritual connection. Big Uncle’s philosophy, and perhaps the very nature of his connection to the “real” world, is something Insu begins to understand and experience for himself as the novel progresses. Big Uncle is a geomancer, which means he can “see” the movement of spiritual energy in the landscape, and he has practiced esoteric Taoist techniques that allow him to experience another dimension of reality. He also uses a little-known method of consulting the I Ching pictographically, and that means he can have glimpses of potential futures.

Insu doesn’t understand any of these things, but through his relationship with Big Uncle, he begins to absorb some of the knowledge intuitively even when it’s at odds with the western worldview he’s learning from his father’s culture. The parallelism with Big Uncle comes to its culmination at the end of the novel during a ceremony performed by Kubong Manshin, a transgender shaman. Thematically, readers might experience the parallelism as a syncretic weaving together of the major Korean traditions—Shamanism, Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism—dramatized through Insu’s point of view.

JC: Speaking of Big Uncle’s esoteric knowledge, you mention in an author’s note that you structured the book with hexagrams and pictograms from the I Ching (not the Wilhelm/Baynes translation with Carl Jung’s introduction, but the older form of the I Ching, known as the Zhou Yi). And that you used your maternal uncle’s (Big Uncle’s) method of casting hexagrams and reading their pictograms before or during your writing sessions to structure the book from the “associative synchronicities” of the Zhou Yi intersecting your memories of 1970s Korea. Can you explain more about that process? How long did it take to write the book? Your sensory details are so specific and immersive, I wonder, did you keep a journal?

HIF: Some of Skull Water was written when I wrote Memories of My Ghost Brother, my first novel. Insu is much younger at the beginning of Ghost Brother, and I wanted to keep the timeframe of that novel limited to the early 1970s. Skull Water begins a little over a year after the action of Ghost Brother ends.

I wrote most of Skull Water between summer of 2016 and winter of 2017, by hand. To start my writing sessions, I typically consulted the I Ching by the pictographic method my Big Uncle showed me, using black and white baduk stones instead of coins. He would draw the ancient pictograms that were the names of the hexagrams and interpret their symbolism as he chanted the verses that went with them. He had memorized the entire Zhou Yi, the older oracular text the I Ching is based on. Most of the pictograms are familiar to me now, but I still have to look up the verse readings in a book. I would usually cast a hexagram at the beginning of a chapter or a scene.

The accompanying pictograms would create a flood of associative images and invoke memories. The pictograms are vivid and concrete, and work almost like Rorschach ink blots—a direct connection to the unconscious, the subconscious, and what Jung considered the collective unconscious. In ancient times, the sages used the Zhou Yi as an oracle to foretell the future. I was doing a similar thing—using the oracle to tell me where I was or foretell where I should be going in my novel.

I didn’t keep a journal. Writing autobiography, especially by hand, is its own form of meditation since it involves the whole body and the breath—it unlocks surprisingly accurate and vivid memories. My friend, Madison Smartt Bell (author of All Souls’ Rising) has a theory about how writing is like autohypnosis, and I think he’s right in many respects

JC: To what extent does American popular culture influence the young men and women in this novel? I’m thinking of Insu’s childhood friend Patsy, who grows up to model herself partly on Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (the two see the film together, and later talk about it). And the food—egg burgers, French fries, Coke.

HIF: American popular culture is a central influence for all the young characters in the novel. For Patsy, the movie, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, offers a romantic narrative to cling to because many of its themes resonate with her and it has a hopeful ending. She uses it to reinvent her sense of self and chart a way forward in excruciatingly difficult circumstances—even if her life is hardly likely to work out like a Hollywood movie.

Of course, for my friends and me, our sense of American culture was filtered through our experiences on military bases, so we were developing a very skewed vision of what life in America was really like. The U.S. military had its own radio and TV stations, AFKN, that produced its own news and aired music and well-known TV shows. We experienced American popular culture in very different contexts. Sometimes we could watch Batman or Star Trek in English and in Korean on the same day.

At the theaters on the U.S. Army bases, we watched second-run movies and lots of spaghetti westerns, musicals, and Blacksploitation films. It was the Vietnam era, and though the Beatles and singers like James Taylor and Glen Campbell were popular, most of the music we listened to was Motown: The Temptations, Diana Ross & the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, and The Jackson Five. I remember a couple of the popular bands that were originally part of the Philly sound: MFSB and Blue Magic, and also Cool and the Gang, who I think started out in New Jersey. My friends and I especially liked Curtis Mayfield’s soundtrack to Superfly and Isaac Hayes’ theme song from Shaft.

Part of coming of age is being able to imagine a future for oneself, and for myself and my teenage friends, we were marginalized in a racist culture in which the typical Korean futures were not open to us. We were searching and trying to connect and bond with each other to find a sense of community and possibility. Listening to music, watching films and TV, and sharing food were all part of this process.

Your question about Patsy and the use of food in Skull Water raises many of these issues. Someone could write a whole book on the theme of food, identity, and coming of age in my novel. My friends and I generally ate Korean food at home, supplemented with some things from the military commissary, where purchases were rationed because of the black market. Our mothers, who shopped there, sold just about all of the rationed items they bought to Korean dealers at about double the purchase price. Those items—instant coffee, Pream, condensed milk, baby formula, Spam, chocolate, M & M’s, breakfast cereals, Phillips Milk of Magnesia, and aspirin—just to name a few—weren’t ones we consumed much ourselves, but when we were on the army bases, we were constantly eating.

This might seem to be because we were teenagers and we were growing, but it was also because we were exposed to a culture of scarcity. Our older Korean relatives had survived the War and starvation, and we witnessed poverty and malnutrition in our daily lives. When we were little, our families ate what was called “pig slop soup” or “military base stew” that was a mix of discarded leftovers from the U.S. Army mess halls heated up in 55-gallon drums and then brought out into the local community and sold by the helmetful. Most Koreans don’t like to talk about that period, for obvious reasons.

One of my fondest food memories as a child is of the time when the main Snack Bar in ASCOM got a doughnut machine and had it running so everyone could see the doughnuts being made. GIs would line up to watch the rings of batter spitting out of a huge funnel into a pool of oil, where they would float down the production line until they were fully cooked and then covered in cinnamon and sugar. My friends and I could only afford three of them, and I remember the Korean cashier telling us, “They’re so delicious one of you could die while you’re eating and the others wouldn’t notice.” That’s a figure of speech in Korean, but you can see how it reflects a history of war and starvation.

At points in Skull Water, the portrayal of black marketing explores how food is literally currency. Patsy’s opportunities to be nurturing with food are meaningful to her and her friends, even though there are always darker undertones relating to prostitution and western consumerism at those moments in the novel.

We can still choose to do what we believe is good even in dire circumstances, and even if it turns out later not to have the positive outcome for which we had hoped.JC: It’s clear there is danger in many circumstances Insu and his mother encounter, when dealing with black markets, money lenders, gamblers. He seems an innocent in a dark world, with many showing generosity toward him. Is that crucial for his survival? Is his character similar to Big Uncle, who as a young man in 1950 finds his way to safety on a train as the North Korea Peoples Army advances on Seoul in a surprise attack?

HIF: In difficult times—like war, or life under a military dictatorship—human nature tends to be amplified. People can become viciously exploitative or surprisingly generous, and any small occasion of exploitation or altruism can eventually lead to profound and unanticipated consequences. Insu and his friends—including some GIs—are enduring the same kinds of oppressive forces; they understand each other’s conditions, and so they help each other even while what they do might also be read as mutual exploitation.

In Big Uncle’s parts of the story—since most of it happens during war time—the consequences of even the smallest actions are amplified to the point of life or death. One of the themes Skull Water explores is how we can never know the ultimate consequences of our actions—good or bad—and that is why the issue of intention is so important. We can at least know our own intentions. We can still choose to do what we believe is good even in dire circumstances, and even if it turns out later not to have the positive outcome for which we had hoped.

JC:What writing projects are you working on now?

HIF:My next novel, The Monkey Puzzle Tree, is about my father’s experience in Vietnam working as a military advisor with the Montagnard tribespeople, the Hmong, in the Central Highlands just before the Tet Offensive. It will be unlike most novels about the Vietnam War because it shows the daily lives and the culture of the Hmong along with my father’s unique perspective.

His family were Sudeten Germans, part of the postwar Expulsion. They lived in Czechoslovakia near Prague, and it’s likely that they were of Jewish origin but passing as Aryan. They endured terrible hardships as they were displaced and resettled, and my father was eventually enrolled by his family in a military school where he was a Hitler Youth during World War II. Very disillusioned about Germany, he eventually came to the U.S. sponsored by Catholic missionaries to work on a dairy farm in Washington State. Later he joined the U.S. Army and was sent to Korea in the late 1950s after the Korean War.

There are lots of unexpected parallelisms between my father’s background and the ultimate fate of the Hmong as they were exploited and then largely abandoned by the U.S. government. It’s another lost history of multiple displacements. Some of Skull Water, particularly the portrayal of Gaines and my father and their storytelling about Vietnam hints at what is to come in The Monkey Puzzle Tree.

__________________________________

Skull Water by Heinz Insu Fenkl is available from Spiegel & Grau.