Heavy-Hitters, Hybrid Novels, and Historians

Zadie Smith, Anne Carson, Michael Chabon, and More

The National Book Awards are presented in an emotional ceremony hosted by Larry Wilmore and introduced by executive director Lisa Lucas. Rep. John Lewis, YA co-winner (with Andrew Aydin and illustrator Nate Powell,) for March:Book Three, Book recalls growing up “very very poor” in rural Alabama, “very few books in our home,” and being told at 16, when he went to get a library card, that the library was for whites only. Nonfiction winner Ibram X. Kendi (Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America) thanks his baby daughter Imani, whose name means “faith” in Swahili. Poetry winner Daniel Borzutzky (The Performance of Becoming Human) speaks on behalf of undocumented immigrants. And fiction award winner Colson Whitehead (The Underground Railroad), referring to the incoming administration, advises, “Be kind to everybody, make art and fight the power.” Michael Chabon’s latest draws glowing reviews, Anne Carson’s is “radiant,” historian Saul Friedlander offers a sequel to his “small masterpiece in the literature of the Holocaust,” Wesley Lowery chronicles the months of reporting behind the Washington Post’s Pulitzer Prize, and more Zadie.

Michael Chabon, Moonglow

A conversation with his dying grandfather inspired Chabon’s new book, a hybrid of novel and memoir that explores his maternal grandparents’ romance and the profound influences of World War II on their lives. Critics approve.

“Mr. Chabon is one of contemporary literature’s most gifted prose stylists,” writes Michiko Kakutani (New York Times).

In Moonglow, he writes with both lovely lyricism and highly caffeinated fervor. He conjures Mike’s childhood with Proustian ardor, capturing his fond memories of his mother (who smelled of Prell shampoo, making him think of those old TV commercials showing a pearl languidly drifting through the mentholated green) and his worst boyhood fears (convinced that a gaggle of evil-looking puppets were lying in wait, plotting to kill him). He makes Oakland, Calif., in the 1970s come alive—and does the same for Baltimore in the 1950s and Florida in the late 1980s.

Michael Upchurch (Boston Globe) also appreciates Chabon’s hybrid approach:

A family can be a riddle that takes whole lifetimes to solve. That’s certainly the case in Moonglow, Michael Chabon’s heady quasi-autobiographical new novel, a picaresque yet sobering tale that unfolds on two continents and encompasses close to a century of family legend and lore. With gusto, it takes on wartime trauma, mental illness, business boondoggles, Space Age obsessions, and hungry Florida wildlife. It examines the ties and barriers between parent, child, grandparent and grandchild, scrutinizing the social pressures that shape them.

The result is the Pulitzer Prize winner’s most probing and substantial book yet.

“We can’t grasp the past simply by knowing it accurately; the facts do not capture either the fullness of a life as it is lived or the mythic power it gains when it is recounted,” concludes Adam Kirsch (Tablet). “Like the moon, we see the past from a great distance, through a transfiguring light. Yet the grandfather spent much of his career working on rocketry and dreaming of a moon landing; and as we know, in the end, humanity did get there. This novel is Chabon’s Apollo mission to the past, launched with the same combination of ingenuity, dedication, and wonder.”

Anne Carson, Float

Float is “a transparent slipcase containing 22 chapbooks to be read on ‘shuffle,’” Carson tells The Guardian’s Kate Kelloway. Reviews are glowing.

“Her poems feel like anarchic rainfall, a fresh shower, an escape from the canyon,” writes Annalisa Quinn (NPR). She concludes:

Throughout Float are these gestures of power and of rage: taking back the story, or, failing that, ruining it. Biting the apple, lighting the fire, marking the letter, blowing the kazoo. “If you are not the free person you want to be, you must find a place to tell the truth about that,” Carson writes at one point. She herself has written something wild and weird and luminous. She writes how you might write if you were not constrained, not afraid of being misunderstood. We can’t be free all the time, but Carson provides the hint of a door—or, failing that, a match.

Kirkus Reviews’ starred review calls it “a radiant delight for Carson’s many admirers.”

Saul Friedlander, When Memory Comes and Where Memory Leads

In his first memoir and its sequel, Friedlander, the eminent Holocaust historian, offers us a dual look at his life–in real time and distilled through the layers of time.

Adam Kirsch (The Tablet) calls When Memory Comes “a small masterpiece in the literature of the Holocaust.” Its new sequel, he writes, is a more conventional kind of memoir because it deals with a more normal, adult life, but it displays the same probing intelligence at work.”

“When Memory Comes was written in the key of memory, a register replete with sensation and emotion but that can offer no lessons,” writes Michael S. Roth (Wall Street Journal). “Where Memory Leads is written in the key of history, a register that moves from meaning to message. Here, the author is crystal clear. ‘The only lesson one could draw from the Shoah was precisely the imperative: stand against injustice.’ Obligation fulfilled.”

Wesley Lowery, They Can’t Kill Us All

The Washington Post staffer who reported on Ferguson and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and was part of the team that won a Pulitzer for tracking police shootings of black men follows up with a well-received nonfiction chronicle.

Alyssa Rosenberg (Washington Post) calls Lowery’s book “a brief guide to many of the deaths that sparked Black Lives Matter, and to many of the personalities that emerged around what Lowery has described as something better understood as an ideology than a movement.” She adds, “I think the book ought also to be read as a primer about the many granular challenges involved in doing journalism today,” as it “captures many of the new factors influencing the profession,” including technical tools such as Snapchat and Periscope.

Mike Fischer (Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel) also notes how Lowery shows the influence of social media on his reporting:

He’s attuned to the tension between traditional and social media, noting the integral role that Twitter played in rapidly spreading news and organizing protests. He himself elects to tweet rather than record at one point, reasoning that he could live with “a more disjointed and incomplete set of direct quotations” if it meant he could stay on top of “a story that had played out on social media.”

The “most eloquent passages,” notes Wendi C. Thomas (Chicago Tribune), “come when Lowery reveals the emotional cost paid by those who write the first draft of history, especially when the writers are journalists of color.” She adds:

Lowery shares his thought process as he figures out how to delicately approach grieving relatives. He shares his skepticism for the accounts offered by official sources. He shares how he maintains a professional distance from organizers and activists while still cultivating them as reliable sources.

Lowery’s strength lies in the breadth of his reporting and the depth of his introspection.

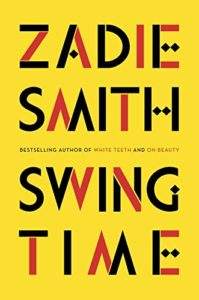

Zadie Smith, Swing Time

Smith’s exuberant new novel continues to garner critical praise.

Swing Time, writes Walton Muyumba (Los Angeles Review of Books), “is a layered and intellectually intricate narrative about black Anglophone cultural experiences in London, Gambia, and New York; Hollywood musicals and cinematic dream worlds; and white performers who can blanch their origins and appropriate blackness in its varieties. Given its similarities to Smith’s earlier fictions, especially White Teeth and NW, Swing Time’s ambitions ought not surprise us, and yet, the effort Smith asks her readers to exert in penetrating this gorgeous, unwieldy novel seems new.”

Laura Miller (Slate) calls Swing Time a return to the “lyrical Realism” Smith wrote about in her November 2008 New York Review of Books essay, “Two Paths for the Novel.” “To live in the syncopation between what ought to be and what is, in swing time, is to know that the latter, for all its unruliness, is always more human and often more interesting,” she concludes. “Every once in a while, it can even be more beautiful.”

“Swing Time is remarkably light on its feet, more entertaining than didactic,” concludes Heller McAlpin (San Francisco Chronicle). “Smith’s humor is both sharp and sly as she skewers various targets, including humorless, petty social activists and celebrity culture’s inflated sense of importance.”

Watch: Daniel Borzutzky talks to Lit Hub at the National Book Awards on figuring out who you are as a writer.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.