Heading North to Become

a Poet

Michael Torres on Navigating the Space Between Home and Away

One of the first times a poem of mine was published, I sent a copy of the magazine to my homie Miguel. He and a handful of other homies had introduced me to graffiti in Pomona when we were teenagers—the culture that would define my high school years. The poem I published looked back on those times painting walls. I wanted to know if I’d done them justice.

This was 2011, a few years after he moved, a few years after I’d started at the local community college. He called me when his copy arrived. We caught up for a while, asking about each other’s parents, talking about work and how the homies were doing. It had been about a year since I’d seen him. He told me he liked my poem. I told him I wanted to be a writer, something I hadn’t yet admitted to anyone else.

Of the homies I was maybe the most quiet or reserved. Miguel, though, was the most vocal, daring, and perhaps because of his experiences, the one with the most insight. In tenth grade he went to juvie after getting into a fight. During that time we kept in touch, writing letters back and forth. In his letters Miguel offered dating advice and reminded me to stay out of trouble.

When I told him I wanted to write, Miguel was excited. It made sense: we were artists. Our crew of graffiti writers valued style and skill above all else. Quality over quantity. I remember meetings in my parents’ front yard where ten or so of us sat around to discuss lettering, color schemes, and brands of spray cans we preferred. I remember keeping paper and a pencil on me, practicing my moniker wherever I went. Art was an option when it felt like nothing else was.

On the phone, Miguel said, “You need to write about us, so they know who we are.” I knew what he meant, knew that “who we are” mattered though we seldom appeared in the books we were assigned in high school English classes, and though we only saw ourselves in movies as a variety of villain or among the oppressed.

The “they” was anyone who didn’t know us, or didn’t care to know us. They were campus proctors, vice principals. They were police and anyone with authority who couldn’t apprehend our complexity, though they named us for us. Graffiti was how we named and defined ourselves. Poetry could be that too.

I wrote a majority of my book in Minnesota. In class and at coffee shops; at the back booth of a Perkins restaurant off highway 169; at a desk in my apartment off 5th street; on morning walks and runs. Through each long winter, and brief bursts of spring, summer, and fall, I wrote about home. And remembering what Miguel said, I tried to capture specific details, to get it right, to craft metaphors that could reach what I felt.

One winter I answered the phone to one of my homies saying, “I haven’t seen you in a minute.” It was true, but I’d written so much and so often about Pomona and my homies that in my mind we’d never lost touch; we stayed talking all the time. But being away from the source of the work, the poems became the way I could still draw close.

I’d moved to Mankato, Minnesota for grad school in 2013, but I stayed to teach and began to build a life out here. Writing those poems about my hometown, excitement for the responsibility Miguel had given me slowly transformed to a kind of worry. In leaving Pomona, I’d gained a valuable perspective but it was accompanied by loss. Over time, Miguel’s words began to seem more like a premonition. It was as if he knew that writing would take me away from home, away from a community that had first nurtured my creative self.

There’s this saying in Spanish I often heard growing up: “Dime con quien andas, y te diré quien eres.” In English it means, essentially, to be careful who you choose as friends. The most literal translation, though, the translation I favor is: “Tell me who you’re with, and I’ll tell you who you are.” It’s true, I felt my homies were an extension of me and I of them for how much timed we’d spent together. So when I wrote, I was always compelled to write about our experiences growing up.

Capturing those years in poems, however, seemed newly crucial in Minnesota. With the physical distance, the possibility of estrangement loomed as I wrote. In writing poems “about us,” to “tell them who we are” I felt not just a responsibility to my homies, but my own need to stay connected to them.

Can I be the person who defined himself among graffiti artists when defining the self as anything felt enormous and nearly impossible?As the collection took shape, I found I was writing as much about leaving Pomona as Pomona itself—that is, the effects leaving has on the speaker, especially as he makes a new life in the Midwest. Writing the poems that would become my first collection allowed me to explore the moments that made me who I am. Times when homies defended me, when they told me to stay behind while they fought, times I ran back after gunshots and jumped fences, realizing one of them hadn’t made it out of the party. There was, and still is, an intimacy built out of that, the foundation of friendships I still value today.

I’ve been reconsidering what Miguel said to me, now years ago. Reconsidering my worry. What I think now is that I’m not here to tell them we matter. Rather, the ones I’m writing to and for, what I have to say—it’s for us. Perhaps what I fear is becoming unrecognizable. To my homies, to Pomona, and ultimately to myself.

Who do I get to be in Minnesota? Can I be the person who defined himself among graffiti artists when defining the self as anything felt enormous and nearly impossible? If not, what do I become? The book in many ways is an exploration of this fear. The speaker of the poems grapples with the understanding and the possibility he could turn into something else again, something he doesn’t yet have a name for.

Though I finally chose to leave Pomona, the poems reach for the version of myself that is most clear in Pomona, the self that finds belonging. And in this way, if I can make the poems say, “Look, it’s me, I’m still here,” then it will be true.

__________________________________

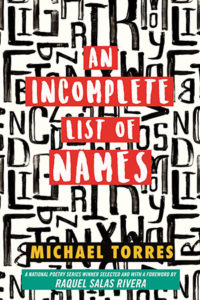

Michael Torres’ An Incomplete List of Names is available now.