“He Was Savile Row, Man.” On the Inimitable Style of Charlie Watts, Rock N' Roll Drummer

Paul Sexton Looks at the Best Dressed Member of the Rolling Stones

Even at the age of two, Charlie Watts had style. The charming photograph that was widely shared on his death, of him in London with his parents in 1943, has him in a short, chic, double-breasted coat, complemented by the courageous but brilliant addition of a beret. His die was cast when his father took him to a Jewish tailor in the East End, and once Charlie started not only listening to jazz but looking at the stunning covers of records by Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington and all, he was in love.

“His style of dress comes from my dad, who was very smart,” confirms his sister Linda. “Dad used to buy material and had suits made, and always wore a trilby, never a cap, to go out. Every night, he would polish his shoes, and Charlie was exactly the same—and so am I. We went to see him one day and he was sitting there in a smoking jacket. He loved clothes.” Her husband Roy adds: “He used to be the country squire. He walked from the house to the stud farm with a couple of dogs, and he’d be walking up the road eating an apple. Then he’d have a wander around the stud farm and come back.”

When Charlie died, long-time admirers GQ said that his personal style “should be your blueprint for buying a suit in 2021.” An editorial noted that his suits “always leant into his rock star roots, with broad lapels, striking structured silhouettes and willowy flared trousers. His styling choices lent him the kind of presence you simply couldn’t get from a boring navy or grey business suit, without you quite being able to put your finger on how he was doing it.”

On the road around the turn of the 2000s, Chuck Leavell was backstage with Charlie and Keith Richards. “We were chatting, the three of us,” says the Rolling Stones’ touring music director and keyboard player, “and this fellow walked up who I didn’t know. I guess maybe he knew one of the others. He was pretty well dressed, he had a really nice jacket on. We talked a little bit and Charlie complimented him on the jacket. The guy just lit up, he was really happy. We made small talk and then he turns to go away. As soon as he got out of earshot, Charlie said, ‘Shame about the shoes.’”

From his silver hair to his handmade shoes, Charlie was approximately 68 inches’ worth of understated style—a fashion victor, never a victim, with a quiet but essential elegance that many attempt but few can achieve. I recall once visiting him in his hotel suite in Amsterdam during a European tour, everything laid out just so and with a Miles Davis album playing gently, chosen with precision from a traveling CD case. Jeans and trainers were beneath his contempt. He was the elegant uncle you never had.

“He was Savile Row, man,” says Keith Richards admiringly. ‘He could have lived there. I said, “Why don’t you marry a tailor?”’

At the end of a show, when he put his official Stones jacket on to keep warm and take a bow, he did more for official merchandise sales than any marketing campaign. Backstage, he could even carry off the bathrobe with the tongue and lips logo he was so proud of. “It had to fit a particular way,” remembers vocalist Lisa Fischer.

“He had such a great sense of style. He seemed like he would just be happy designing clothes. Not that I could see him as a model, but I would see him as somebody that would be tailoring clothes. If he wasn’t a drummer, design would be his thing. He just loved textures and quality and looks, and he looked so great in his clothes. Very few people can pull off pinks and blues, and he just did with no problem. If anything, it would bring out the pink glow in his cheeks. He’d be kind of shy, but still knowing he looked good.”

One such instance was when Charlie and Shirley rose to the occasion of Royal Ascot in 2010. With his beautifully demure and quietly glamorous wife proudly on his arm, he went to town in top hat, sunglasses and a double-breasted dove-grey morning coat custom-made by Huntsman, his tailor, with diagonally arranged buttons. The waistcoat and tie were both pale pink, the rounded collars of his shirt pinned beneath the knot of the tie. Study the cover of saxophonist Dexter Gordon’s Blue Note classic Our Man in Paris for the inspiration that Charlie was happy to credit. It was the same when he saw Miles Davis looking cool and relaxed in a green shirt on the sleeve of 1958’s Milestones: he, and every aficionado of jazz style, had to have one.

At Savile Row tailoring house Huntsman, which has made clothes for the discerning since 1849, Dario Carnera tells me of his family’s proud history of having Charlie as a customer and a friend. Such was their relationship, a fabric designed by the drummer himself, the Springfield stripe, remains in their catalogue. “He was Savile Row, man,” says Keith Richards admiringly. ‘He could have lived there. I said, “Why don’t you marry a tailor?”’

After Dario has introduced me to the cutters who made Charlie’s bespoke suits and jackets—and shown me, with huge poignancy, the last four beautifully cut jackets that he commissioned but never collected—we walk around the corner to the Royal Arcade, Old Bond Street. Here we step even deeper into a world of London craftsmanship that most will assume has been lost.

We are meeting Dario’s semi-retired father and master shoemaker John, who made Charlie’s beautiful footwear for the better part of 30 years at family business G. J. Cleverley. Its list of clients has included Winston Churchill, Humphrey Bogart and the Prince of Wales. This is a craft far removed from the modern world of instant gratification: Carnera Sr’s apprenticeship alone lasted five years. Soon after John took over the business following the death of founder George, he had a new visitor. “Charlie comes to the door,” he remembers. “I said, ‘How are you, Mr. Watts, isn’t it?’ He said, ‘Yes,’ very understated. I said, ‘Please come in,’ and he said, ‘I wondered whether you’d make me some shoes?’ I said, ‘I’d be delighted.’ He said, ‘I have got a shoemaker but they’re taking rather a long time to make them. Can you do them faster than two and a half years?’

“I said, ‘I think we can guarantee that. The first pair would take three to four months.’ ‘Oh, that’s wonderful,’ he said. ‘You’ve got some nice shoes. Will you measure me?’ Almost like, ‘Will you do me a favor?’ That was the way he was. So we measured him, and, beginning in 1993, we went on until 2021.”

John shared Charlie’s passion for jazz, and reminisces about hanging at Soho dives in the late 1950s and early ’60s, especially the original Ronnie Scott’s, now commemorated with a blue plaque. “I always remember going down to that basement,” says John, echoing a conversation he would certainly have had with his famous client. “It was next to the post office in Gerrard Street. Pokey old hole, but I always remember the lineup. There was Ronnie Scott, Tubby Hayes, Phil Seamen on drums and I think it was Johnny Hawksworth on double bass. Charlie and I used to have some great discussions.”

A pair of handcrafted shoes from Cleverley’s will generally take six months to make, and cost in the region of £4,000. They only make a dozen pairs a week in total. Charlie had at least 80 pairs made there, with the “Cleverley toe” (“like a chisel toe,” John explains. “Every time we finished a pair, he’d say, ‘What haven’t I had, John?’”).

Adds Dario: “He had such slim, elegant feet [“The foot that everybody dreams of,” notes chief lastmaker Adam Law]. He’d come in, if he was collecting something, and say, ‘What do I need? Well, I don’t need anything, what do I want?’”

As Charlie developed his friendship with the family, he would invite them to Stones concerts, and his own, around the world. John Carnera laughs at one particular memory concerning the group’s financial guru Prince Rupert Loewenstein. “He used to have his shoes made by Cleverley’s nephew Anthony, who was an even better shoemaker than George, although you would never tell George that,” he chuckles.

“Anyway, Anthony used to go and see his customers privately, he didn’t have a shop, and Loewenstein was one of his best customers. He had a flat off Kensington High Street. He went to see him to deliver this pair of shoes, to try them on, and Mick happened to be there. Loewenstein said, ‘Well, as usual, Mr Cleverley, great pair of shoes, blah blah.’ And Jagger’s looking on and saying, ‘Lovely pair of shoes, Rupert.’ He says to Anthony, ‘Would you make me a pair of shoes like that?’ He said, ‘No, I’m not having you prancing about the stage wrecking my shoes.’ As far as he was concerned, he could have been John Smith.”

Talk of Prince Rupert reminds John Carnera of another story, about one of Loewenstein’s associates. “The Charlie connection is that when the man died in 2004, Charlie’s ears pricked up. He said, ‘Do you think I can get hold of some of those shoes, John?’ I said, ‘I understand they’re having an auction,’ and he went over to Paris and bought some of them. I think he bought something like a dozen pairs.”

Charlie may have insisted on old-school artisanship, but there was one tradition about hand-made shoes that he didn’t agree with. He felt it was the customer’s own responsibility to break a new pair in. He said: “Most of the aristocracy who could afford to have shoes made would have the gardener or butler wear the shoes first, to break them in.”

By contrast, Rolling Stones keyboard player Chuck Leavell remembers a touring story. “In Madrid my wife Rose Lane and I had got up, and it was fairly early. We were going to go out to a museum or something and Charlie was in the lobby. I was a little surprised, because it was like 8:30 AM or something. So I asked him where he’d been, and he said: ‘Taking my new shoes for a walk.’ How brilliant is that?”

As the Rolling Stones became the talk of every town in the 1960s, Charlie became a customer of celebrated fashion maverick Tommy Nutter, who practically clothed showbusiness, and rewrote the rules of the Savile Row suit in the process. Charlie then became a customer not just of Huntsman but also Chittleborough & Morgan, co-founded by Roy Chittleborough and Nutter’s graduate Joe Morgan. It was there that he bought his friend and work colleague Tony King a suit as an end-of-tour gift.

Charlie would arrive on the Row in his chauffeured limousine, learning to love and respect the nuances of tradition and custom unique to each tailor. His fondness for wide lapels and statement cuts helped him present a more imposing figure than suggested by his modest frame; indeed he would say that if a favorite pair of trousers was becoming a little tight around the waist, he simply wouldn’t eat until they were comfortable again.

On stage was a different matter: he would have loved to emulate the formal, jacket-and-tie dash of another hero, Art Blakey. But after wearing jackets as a young man, he later opted for the sensible work clothes of a T-shirt or short-sleeved shirt. Even those were custom-made—you somehow knew without asking that they weren’t going to be off-the-peg. Sunspel, the British clothing manufacturer dating back to the 1860s, designed a T under the guidance of stylist William Gilchrist that was easier for Charlie to play in. It inserted an extra side panel, allowing for two seams down the side instead of one, and with a shorter cut than the normal. He was so pleased with the results that the entire band wore the design at the Glastonbury Festival in 2013. His fashion knowledge extended far beyond his own tastes or his own clothes. “When we first started working,” says producer Chris Kimsey, “my wife Kristy was with me a lot of the time, travelling and working. He turned her on to Opium, the perfume, which had just come out. Working with him in Paris was terrific. He used to take me round all the vintage suitcase shops, because he’d got a collection of suitcases, and the hat shops as well.

Charlie would arrive on the Row in his chauffeured limousine, learning to love and respect the nuances of tradition and custom unique to each tailor.

“Every session he walked into, he was always so smart, so beautifully dressed. Something that he and Glyn Johns shared—Glyn, my mentor, said to me at a very early age, ‘Kimsey, make sure you dress sharp for every session.’ Every evening when we’d start the sessions in Pathé Marconi in Paris, Charlie would be one of the first to arrive. He hardly ever came in the control room. He just walked to his drum kit, took off his jacket, folded it perfectly, hung it over a chair and got himself settled with all his little accoutrements. Really like unpacking everything.”

Adds Lisa Fischer: “Near Charlie’s drum kit, even at rehearsal, there was always this little place where he could hang his jacket. It was like he was going to his office. I loved his little space.”

________________________________

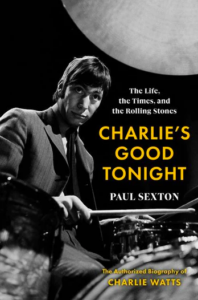

From the book CHARLIE’S GOOD TONIGHT by Paul Sexton. Copyright © 2022 by Paul Sexton. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Paul Sexton

Paul Sexton started writing about music as a teenager in 1977. His work has appeared in The Times (London), the Daily Telegraph, the Guardian, Billboard, and numerous other publications. He has made many documentaries and shows as a presenter and producer for BBC Radio 2, and is also the author of Prince: A Portrait of the Artist in Memories and Memorabilia and Charlie's Good Tonight. He lives in South London.