1

The haymaker’s name was Knut Hansen Nesje, but folks just called him Nesje and they called the farm he leased on the hillside above the small town of Molde on the west coast of Norway “the Nesje parcel.” Nesje was my great-grandfather, and during my childhood I heard many stories about him from my grandfather, Edvard Hoem, and my father, Knut.

But, although I know the key dates in his life and have a few documents about how he lived, when I went to write about him, it was not enough. I had to invent him out of air and nothingness, out of the light over Molde and Rekneslia, out of the wind that tousles my hair and the rain that falls over the fields and the people, both in his day and in mine.

On June 17, 1874, he woke up earlier than usual in the house he had built below the horizon. The pocket watch on the chair beside his bed said five o’clock. His heart beat erratically the way it did when he was short on sleep, and he thought, as he usually did when it thumped like that, that our minds bear many a worry that we do not comprehend.

He lay still a while before it dawned on him that today was his birthday and he would be thirty-six. Two years had passed since his wife Guri had died. For the first time, he now felt that time was easing his pain and longing.

He swung his feet over the side of the bed, descended the steep attic stairs, and went out behind the house to pass water. The summer morning was waking up with floral scents and steaming sod. He heard birdsong farther up the hillside—at first a thrush, then a chorus of starlings, chaffinches, and willow warblers.

He went back inside and drank his fill from the dipper that stood in the rainwater bucket before pulling on a pair of wadmal pants that had once been his Sunday best, a linen shirt, a vest, and a neckerchief. The window was open. A pair of starlings reared a brood of chicks in a nest under the eaves. He buttered a heel of bread and drank a mug of milk with it. He didn’t usually make coffee on weekdays, but if Claus Gørvell’s servant girls should offer him a cup later in the day, he wouldn’t turn them down. In his youth he allowed himself a dram on his birthday, but he hadn’t tasted the stuff since he became a widower. A tenant farmer had no time for drinking or idleness. Summer days at the Gørvell farm were long and hard, and when the haymaking was finished he still had to do his six days of contractually obligated mowing for Reknes, from whom he leased his land. In addition to this seasonal farm work Nesje also made tools at the workbench and in the forge, and he took care of those Danish draft horses Claus Gørvell loved so much.

During the haymaking, he always led the line of five scythemen. He set the pace for their mowing. His work at the Gørvell farm meant that he mowed his own parcel at night, and during the busy season in the summer that usually meant no more than three or four hours of sleep. In the winter he worked in the woods for Gørvell. He worked for a half dalar a day, or sixty skilling as people called it, which was less than a day’s wages for a day laborer. But Nesje worked on the Gørvell farm year-round. In the spring and fall he spent every free moment clearing, sowing, and harvesting the four acres of land he had leased in Rekneslia. In only ten years he cleared and plowed two and a half acres. He had one and a half to go. He tilled the soil with a spade and a mattock. Only for the plowing did he borrow a horse. By his fortieth birthday, he would have all the land under his control converted to hayfields and cropland. That was his plan, at least, and so far he had stuck to it.

2

Before Nesje left the house, he yelled at the attic to wake his fourteen-year-old son, Hans, who worked as the errand boy at the Gørvell family’s mercantile for the summer. Nesje heard no response. He grabbed his ax and pounded on a rafter with the ax handle until the boy came stumbling down the stairs.

“Stop, I’m awake!” mumbled Hans from a rung. He ladled water into a small basin and headed out the door to wash the sleep from his eyes. Then he came back in and put on his clothes, which were sitting on a chair. Then it hit him.

“Happy birthday, Pa.”

“Thank you.”

Nesje looked at his son. He had shot up really nicely the past couple of years. He had curls in his hair that he tried to flatten in the morning with water. He had a gentle face, almost delicate, and like so many other members of the Nesje family, he tended to his hands and fingernails well. Hans would be confirmed next spring. It’s often said that children are only ours on loan, but Nesje hoped the boy would settle nearby when he grew up. It was just the two of them, after all, and who knew what the future would bring. So many people were setting out across the Atlantic to America in those days, without any regard for their parents, who were left behind in misery and destitution.

Nesje’s voice caught a little as he reminded the boy, as he had every day of his life, to be on his best behavior. The boy eyed his father carefully and, quietly, placatingly, he replied, “I will, Pa.”

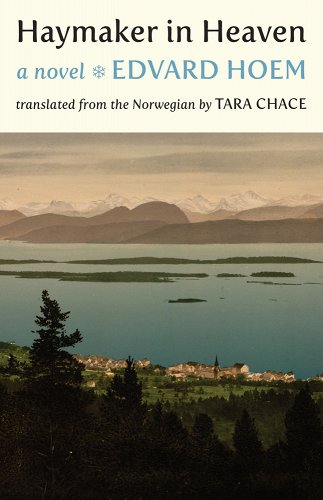

Nesje picked up his whetstone from the table and secured a sheathed whittling knife to his belt. Then he walked down the big stone steps and paused for a moment in front of the house. The mountains on the far side of the Molde Fjord were an incomparable sight on this misty morning. The view of the mountain range was a major reason why he’d decided to settle so high on the hillside. Some of the mountains across the fjord were near the water, others farther inland, but they were all spectacular from here, like one contiguous chain of more than seventy peaks. There was still snow on most of them. And the surface of the fjord was smooth and still. In the early morning, the islands and islets looked as though they floated on the water.

Nesje jogged down the hillsides and didn’t stop until he reached the top of the hill at Rekneshaugen. He paused there, giving some thought to his age. I’m an adult, he thought, but not yet old. He looked out over the landscape. He lived here, and this was where he would continue to live. He was a thin man with a full beard and hair that curled when he sweat. He always wore a hat in the field, so his face wasn’t too sun-burned, but his forearms and hands were dark brown. There was nothing a laborer could do about that.

Below him lay the little town of Molde, which had grown up on the land belonging to the Reknes estate and, just across the Molde River, Moldegaard Manor. A row of houses lined both sides of the old carriage road between Reknes Hospital and Moldegaard, and each year new buildings were added.

Nesje walked down the path to the right of the Humlehaven, the large “hops garden.” This was all fields and no buildings on the outskirts of Molde, which was technically still a part of Bolsøy, the neighboring town. The hillside was fenced in to keep animals out, with several hundred plant species that now, in early summer, were in peak bloom. The garden was called Humlehaven because Judge Advocate Koren, who at one time owned the large Reknes estate, raised hops for brewing beer. Humlehaven now belonged to the Dahl family, and the skippers of Nicolay Dahl’s ships, who sailed many oceans, had instructions to bring home all the exotic seeds, rootstock, and cuttings they could find, to see if these would grow in Molde. In its floral splendor Humlehaven was a wonder to behold so far north. The Dahl family’s arched and columned gazebo stood atop the hill, and the steep slope below was covered in rosebushes, clematis, and honeysuckle. Through the garden, wind rustled the crowns of larch trees and stone pines.

Nesje inhaled as he walked by. The course of life is like the cycle of the seasons, he thought.

He came down onto the lane lined with ash trees that Claus Gørvell planted a couple of years earlier, after the birch trees that had grown there since the time of Judge Advocate Koren were chopped down. The ash trees were not yet head high, but even so, people referred to the unfinished lane as Gørvell Allée.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Haymaker in Heaven by Edward Hoem, translated by Tara Chace. Published by Milkweed Editions. Copyright © 2022. All rights reserved.