Have you purchased a weirdly low-quality paperback book lately? This may be why.

I work as the bookstore manager for a bookstore in the Hudson Valley and one of the things that means is that I handle not only the ordering of most of our books, but the unboxing of them as well. I get to put hands (or at least eyes) on basically every book that comes into the store and, as a result, I’m well-positioned to notice trends in the quality of the physical releases heading out into the world these days. Some of them are positive trends, or at least morally-neutral late-capitalist cash-grabs like the rise in sprayed edges or the hardcover reissues of popular novels that already had a hardcover release. But in the last few weeks, I’ve noticed a significant uptick in print-on-demand paperbacks: low quality covers and paper, often poorly printed, and listed at a higher price than their regular-print brethren.

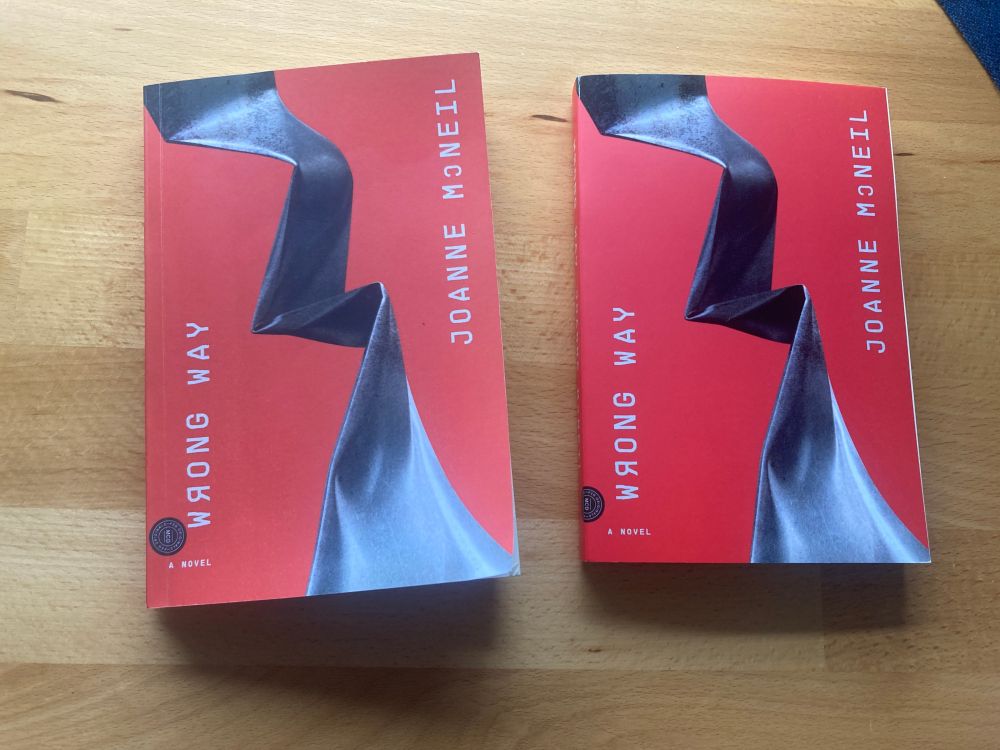

Earlier this year, Joanne McNeil posted on Bluesky about something strange that happened with her then-brand-new book, Wrong Way: an Amazon order delivered a copy of the paperback-original that was a different size, on lower-quality paper, and featuring a slightly different cover. As McNeil pointed out, many consumers likely don’t know the difference between a print-on-demand book and a traditionally produced paperback, at least not at first. But once you do notice, you can’t unsee it.

On the left is the print-on-demand edition of Wrong Way. On the right is the publisher-printed edition. (photo credit: Joanne McNeil)

The thread on Bluesky quickly devolved into self-published writers griping about McNeil’s exhortation to not buy paperbacks from Amazon because that’s the only place they can sell their books—a flawed argument on so many levels and a fight I’m not interested in having today, but one that comes with a good point: print-on-demand is not new, nor is it unequivocally bad. Yes, most self-published books suffer for lack of an editor or paid cover designer, but the technology itself has many uses: it is an easy way to do a small print run of something, to share niche research, to reissue old books otherwise lost to time, to print vanity projects or commemorate a special event, and plenty of other things besides.

It is also basically fast fashion for books, and I’m worried that the sudden rise in “cheaper” paperbacks might have a long-term negative effect on the publishing industry.

First, some context: bookstores can get their books either directly from publishers or from Ingram, a distributor/middle-man that warehouses and ships out books from just about every publisher in existence. Ordering directly from the publisher can often provide a slightly higher wholesale discount, but it usually takes longer to get books; ordering from Ingram is often faster, if a little more expensive. Ingram also works with self-published authors and some smaller publishers to print their books on demand—the rationale being that it’s cheaper to not warehouse tons of books that you might not sell, and for small print runs, it can make sense to only print what you know is already sold. I’m happy to sell a print-on-demand book from a small publisher, because that can often be the only way those books are getting out into the world. The issue comes when major publishers have books going to print-on-demand without the authors, booksellers, or customers knowing about it.

You may have seen the news that, after winning the Nobel Prize, Han Kang has hit the New York Times bestseller list—with The Vegetarian, a book that came out eight years ago. Objectively, this is a good thing: people are reading a weird, freaky book by an author who deserves much more attention and acclaim. Subjectively, I can attest that every copy my shop has sold in the last few weeks has been a poor-quality print-on-demand edition of the book instead of the original paperback that I have on my shelf. All of these books came from Ingram—and I should note that my store currently orders the majority of its stock from Ingram, for reasons of efficiency and time.

Do I think that every copy sold in the last two weeks has been print-on-demand? No. But I am willing to guess that most of them, ordered in the rush of excitement that follows the Nobel announcement every year, were printed at Ingram after the orders came in.

After posting about this on Instagram, I heard from several authors who were horrified to discover that their books might be getting this quality-dip. Some of them expressed concern about their contracts and royalties, that they might be making less money from a print-on-demand version of the book, while others were simply shocked to see the product of their labors—and the labors of designers, editors, marketing and publicity staff, and more—given such short shrift. One of my favorite books of the last decade (shan’t reveal it here, you’ll have to come see me in the store about it) arrived as a print-on-demand edition this week with the cover printed from a low-res file on glossy stock. It looks like a fake book, something you’d get from a shady internet seller—not an indie bookstore. And we ordered it from Ingram!

I also heard from editorial directors and other managerial staff at several publishers, all of whom cited the still-reverberating impacts of COVID on the supply chain, on the price of paper, on the workforce. I was treated, more than once, to the classic line that “authors and readers don’t understand how thin our margins are” and several people pointed out that this trend is being driven by publishers: it is cheaper for them not to warehouse books that might end up getting pulped. Amazon also charges publishers a fee if a title goes out of stock, hence the increasing reliance on print-on-demand there.

But margins in bookstores are far thinner than those at publishing houses—and the fact that bookstores are now having to pay more for lower-quality books (the wholesale discount is usually between 8-10% less for a print-on-demand title) is going to mean that fewer stores will take on these backlist titles, leading to a homogenization of inventory across the field. And readers are going to notice too: these print-on-demand paperbacks are not only more expensive for the bookstores ordering them, but they’re also more expensive to the consumer to the tune of $3 to $5. It’s bad enough that hardcovers are now largely over $30—but paperbacks breaking the $20 line at decreased quality is absolutely going to turn readers away.

As I unboxed a shipment this week of about a dozen different titles, all of which had clearly been printed on demand, some of them so obviously cheap that I was embarrassed to put them on the shelves, I had to wonder: is it really worth it, to get books into readers’ hands faster? Nobody needs a book the same day they order it, as one might need medicine or perhaps a plunger to fix an overflowing toilet. The siren song of convenience has led us to a place where publishers are willing to charge more for an inferior product—and while fast fashion shops like H&M, Zara, and Forever21 continue to sell plenty of mass-produced clothing at the expense of the environment and their workers, the tide has begun to turn against that trend. I have to hope that the publishing industry will see the light and, at the very least, make this move more thoughtfully… but hope is all I have.

Drew Broussard

Drew Broussard is a writer, podcaster, bookseller, and producer of creative events. He spent nearly a decade at The Public Theater before decamping to the woods of upstate New York, where he lives with his wife and dog.