'Have You Considered Socialism?' Or, The Politics of Fictional Characters

Andrew Martin on Short Stories in the Age of Shorter News Cycles

I started the oldest story in my new book almost eight years ago, during the summer of 2012. I remember sitting on the curb in front of a car repair shop in Missoula, Montana in the blazing heat, writing what became “Cool for America” in my notebook while waiting for a friend to pick me up in her vintage pink Oldsmobile. In the original draft, there was a joke about Mitt Romney, which became a joke about Marco Rubio, which became a joke about Rand Paul. In the final (for now) published version, finalized six months ago, it’s a joke about Ryan Zinke, Trump’s corrupt former Secretary of the Interior and a former Montana congressman. You may be forgiven for forgetting, or for never knowing, who he was.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the ways that books and other works of art change, or don’t, over time, and consequently the varying degrees to which they might be considered “relevant” at different junctures. These are not things that a writer can afford to think about while working on a novel or a short story—it’s the equivalent of looking down in the middle of the tightrope—but the time around the publication of a book affords plenty of opportunities for such thoughts, even if they’re no more useful than at the time of composition.

In this season of illness and mass protest against systemic racism, questions about the relevance and utility of art feel especially pointed, though it has felt that way, to some extent, since at least the summer of 2016, which was so dominated by the specter of Trumpism that it seems right to mark it as the beginning of the Trump era. Both my first novel, Early Work, and Cool for America, my new collection of linked stories, were drafted and edited over a period that spanned the second Obama administration and the first (and, one prays, only) Trump administration. The pace of my own writing and thinking, and of publishing on the whole, is such that these works are more accurately categorized as works of the late Obama-era—a period marked by conservative obstructionism, technological disruption, and deserved fury about the wanton killing of black men—than as responses to the current moment.

As that (admittedly cherry-picked) list suggests, this time has more in common with the era we’re still mourning than we might like to think. This isn’t to draw a false equivalence between those presidencies or times—I have no doubt that Obama would have done a better job of responding to the coronavirus than Trump, even if the current administration’s economic response to the virus owes more than a little to the previous one’s too-timid response to the financial crash. But, unhappily for the country, I think this sense of foreboding, of unstoppable violence and the inability to face it squarely, exists on a continuity with the recent past rather than having emerged as an aberration from it.

My characters have not, thus far, considered socialism. They’re too deep in their own heads for that, even as the world crumbles around them.

As I read through the stories in this collection now, I see a portrait of psychic trauma that I didn’t understand consciously while I was writing. The problems that these are characters are facing are not explicitly understood as political by the people themselves. They are dealing with addiction and despair, grappling with an inchoate sense that things are not as they should be. These are people who are pressed up so close against their problems that they can’t see the bigger picture, rendering themselves more powerless than they need be. In one of the newest stories in the collection, “Attention,” the protagonist is struggling with both sobriety and the terrifying threat presented by the Trump presidency. For her, both are part of a larger internal debate about what one should devote one’s focus to, though she doesn’t quite link the political crisis with her personal crisis. In the story, these things run parallel to each other, relating to each other via proximity rather than argument.

The title of the story “No Cops,” which begins the collection, reads, today, as a manifesto (and I always liked the sound of it, both sonically and politically). But those words are spoken in the story by a probably-homeless man suffering from late-stage alcoholism, pleading with the story’s young, white protagonists not to call the police on him. The story is a portrait of different kinds of isolation, with the protagonist refusing to see herself as part of the community in which she lives, and the man she encounters rejected from it with far less choice in the matter.

There is a genre of writing, often spanning the entire issues of the small magazines I subscribe to, that my partner and I affectionately refer to as “Have you considered socialism?” It is a necessary genre; it has, in its various manifestations, convinced me to consider—and actively support!—socialism. And yet my characters have not, thus far, considered socialism. They’re too deep in their own heads for that, even as the world crumbles around them. They can hardly extend empathy to themselves, let alone to their communities in any kind of sustained way. The last story in the book ends with a character contemplating her future out loud to a woman with whom she’s grudgingly sharing a tent: she might get rich, she might get sick, and she’s already on her way to getting a divorce. Maybe if I’d written the story today her conversation partner would have suggested she join DSA. Instead, she sighs heavily and tries to get back to sleep.

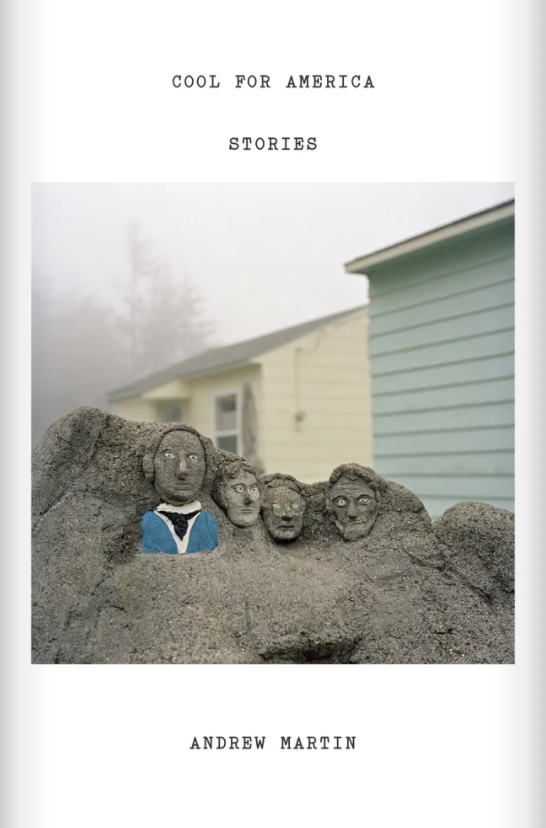

I’m trying to see this moment we’re living through, particularly here in New York, as one of opportunity, one in which the shock and grief and anger we’re feeling might be enough, if we sustain it, to discard and destroy things—Confederate statues, privatized healthcare, overfunded police departments— we’ve been too timid to do anything about. Cool for America, from the title on down, is about the frustrated ambivalence that precedes whatever comes next. When I first saw the cover in October of last year, it struck me as strangely perfect, though I didn’t really know why. It’s a photograph of a misshapen, backyard Mount Rushmore, the faces, either through carelessness, incompetence or willful indifference, bearing only the faintest resemblance to the presidents they are meant to represent. Before, I saw our national myths taken down a peg, democratically shrunken small enough to decorate a suburban home. Now, I see a graveyard.

_________________________________

Andrew Martin’s Cool For America is available now from FSG.

Andrew Martin

Andrew Martin is the author of the novel Early Work, the story collection Cool for America, and the forthcoming novel Down Time.